|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Ethnic Dances of Greece

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

Dancing has always been important to the Greeks. Dance and music were an integral part of ancient Hellenic drama. The Greek word "xopos" (horos) referred to both dance and song. In English the word choir, chorus, and chorale all come from this same Greek word.

Dancing has always been important to the Greeks. Dance and music were an integral part of ancient Hellenic drama. The Greek word "xopos" (horos) referred to both dance and song. In English the word choir, chorus, and chorale all come from this same Greek word.

Traditionally, each area of Greece has been very proud of its own customs and institutions. It has been said that in ancient times, a Greek usually would say he was first a member of his city-state and second a Greek. This is true today. Rather than saying, "I'm a Greek," the Greek will probably say, "I'm a Kritan," or an "Epirote," or an "Arkadian," or a "Macedonian," or whatever. Because of this strong local pride, and also because of the comparative isolation caused by the harsh, mountainous terrain, the customs and folkways of each area usually are somewhat different from each other.

The dances of the Greek people are many and varied. The great majority of these dances are done in a semi-circle moving counterclockwise. Some dances are for men only, some for women only. There are a few dances that are done in couples such as Ballos and Karsilamas, and there are some dances that are for a solo dancer, such as, Zeimbekikos.

Each area of Greece, often each village, has its own dances. Often, two areas will do the same dance, but with different variations or styling. We can even see the same footwork or dance steps done to many different types of music so that it appears to be a completely different dance.

Some dances are common to all Greeks. Examples of these panhellenic dances are: Syrtos, Kalamatianos, Tsamikos, and Hasapikos. These dances, like many of our western social or ballroom dances, are done to an infinite number of tunes. They are not done to only one melody, but to any song with the correct rhythm for the dance. Some Greek dances, however, are done to only one melody.

Greek folk music is different from the music of the West. Whereas the average American is used to rhythms in twos, threes and fours, the Greek sings and dances to rhythms such as 2/4, 5/4, 6/4, 7/8, 9/8, 8/8, and 12/8. It has been determined that these so-called "mixed meters" came from the rhythm schemes of ancient Greek poetry and music. (A commmon pattern was one in which the first of three beats was one and one-half times as long as each of the short beats, i.e., 3-2-2, or 7/8.) Furthermore, Greek music uses more than the major and minor scales of western music. The Greek musician uses intervals such as the quarter tone, and techniques in playing which a trained musician of western music could not duplicate.

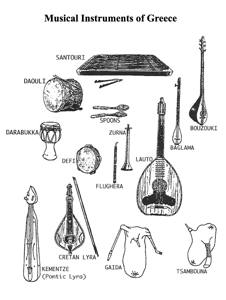

There are many different types of musical instruments used in Greece. Some of these instruments are: floyera, karamoundz, gaida, klarino (wind instruments); lyra, violi, tamboura, lavouto, bouzouki, baglama, santouri (stringed instruments); and tympano, daouli, defi, daire, toumbeleki (percussion instruments). Most Greek musicians are self-taught and don't know how to read music. Often the art of music is passed down in the family from father to son. Just as the dances vary from area to area, the music and instrumentation in each area tend to be different.

MAIN AREAS

On a very simple level, we can divide Greece into two main folkloric areas: the Mainland and the Islands. Each of these areas is further subdivided; the styling of dance and music within each of these subdivisions is similar. A third main area is sometimes mentioned – the coastal, or seaport area, which includes the tavern dances such as Argo Hasapiko (Vari Hasapiko) and the Zeimbekiko.

Mainland

Islands

- Aegean

- Ionian

- Dodecanese

- Kriti

- Kypros

SOME NOTES ON STYLING

In general, all dancers stand straight and proud. Whereas men often have high leaps and large motions in the dance, women usually dance more sedately. They do not swing their legs very far; their feet do not usually lift very far from the ground. Some of the reasons for the "feminine" styling are: culturally, the women are expected to be lady-like and dance in a lady-like manner. Another point is their costumes; the women's costumes are usually multi-layered and quite heavy. Their skirts are also quite long. When dressed in such clothes, it is not easy to kick your feet very far or to make any large movements of the legs. Also, because of the length of the costumes, large movements wouldn't be seen anyway.

WHAT DOES ONE DO WHEN LEADING?

If you are dancing at the right end of the line or semi-circle (leading), your right arm never just hangs free. The right arm is either held straight out to the side at shoulder or head height (often with snapping of the fingers), or it is placed on the right hip. If you are at the left end of the line (the last dancer), you do the same thing with your free hand.

There are some dances where only the leader can improvise turns, leaps, or slaps to the feet. Such dances are: Syrtos-Kalamatianos and Tsamikos. Other dances, such as Hasapikos and Sta Tria, allow all dancers to do simple variations, such as, turning or step variations. Find out whether you are supposed to follow the leader before you attempt to do his variations. And when leading, remember that the variations you do in Syrtos or Tsamikos need not be extremely fancy. The leader is not trying to impress anyone. This is a mistake the novice Greek dancer often makes. A leader's variations are an expression of his feelings in the dance. They are, therefore, an expression of personality and not intended to dazzle anyone watching (even if they are dazzling in effect). They should not be planned and mechanical. A simple turn or two is often more beautiful than 220 slaps of the feet and standing on one's nose to impress the people watching.

DOCUMENTS

- Greece, a country.

- John Pappas, an article.

Used with permission of the author.

Copyright © 2014 by John Pappas. Do not reproduce without permission.

Reprinted from the 1976 Santa Barbara Symposium 1976 syllabus.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.