|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Traditional Macedonian Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

Folk dances of Macedonia are a special feature of the folklore of that land.

Folk dances of Macedonia are a special feature of the folklore of that land.

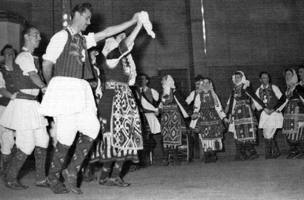

It is quite difficult to give even an approximate lay description of this form or art, for Macedonian dances cannot be spoken of as consisting of mere rhythmic movements of the legs and arms. To each observer, it will mean a different thing, and he may speak in flowing terms of what he observed – the dance is strong, elegant, has subtleties, emotionally moving, rich choreographically, etc. – or it may be that the meaning is incomprehensible or the musical accompaniment harsh or unusual in rhythm. There are a few, however, to whom Macedonian music and dance means very much, and they have been able to penetrate to the inspiration that produces these impressions.

As a rule, Macedonian dance is sustained, as if the foot is feeling cautiously for firm ground at every step. It often begins with motions similar to some religious ritual, starting almost without any discernable beat, but as it progresses, gains more and finally reaches a very high rhythmic level; it gains rapid momentum, them dies out at its peak – such as a symbol of the achievement of its goal. This pattern has a beginning, a middle, and a finish which is the climax, and the dancer does not abandon it at that point because he is exhausted – rather, the sequence of frames is completed and the dance has told its story.

Forms of Macedonian dances are of much interest because they are so often taken directly from the acts of daily life in which someone during his hours of labor, repeats certain motions countless numbers of times. These movements become prime choreographic material, so you will find dances of butchers, coppersmiths, herdsmen, shepherds, and of course, warriors. Probably the most powerful of these are the dances that portray the struggles of the "komitaži," those Balkan guerillas who battled against the invaders of their land for two millenia.

The dances most physically taxing come from the western mountain regions, where, living literally on the edge of precipices and cliffs, the shepherd, guerilla, or hunter had to step warily for secure foothold, yet at the same time be on the alert for danger to his flock or to himself from feral animals, the enemy, or bandits. This air of wariness and militancy is seen expressed in the stress and balance of the course of the dance. To the east, where man was more subject to serfdom, the dances are often seen with much striking of the earth with the foot, as though attempting to free himself from its hold, yet being unable to do so.

The complexities of the choreographies and rhythms of Macedonian dances are linked directly with its musical rhythm, which is in itself unique to Western ears. They are regularly done to musical instruments, and occasionally to voiced songs. A very few are done silently, and these seem to be remnants of the feudal days when the humiliating privilege of the "first night" was that of the feudal lord so the peasant had to celebrate his wedding in the woods or mountains, silently and without festivity or music if he wished to save the honor of himself and hius bride. In general, the Macedonian dance form is one of a dance of nerves and of all parts of the body, and the movements blend emotions that have evolved through the centuries.

The complexities of the choreographies and rhythms of Macedonian dances are linked directly with its musical rhythm, which is in itself unique to Western ears. They are regularly done to musical instruments, and occasionally to voiced songs. A very few are done silently, and these seem to be remnants of the feudal days when the humiliating privilege of the "first night" was that of the feudal lord so the peasant had to celebrate his wedding in the woods or mountains, silently and without festivity or music if he wished to save the honor of himself and hius bride. In general, the Macedonian dance form is one of a dance of nerves and of all parts of the body, and the movements blend emotions that have evolved through the centuries.

Regarding these random reflections on Macedonian folklore, perhaps a cursory explanation should be given regarding the material, historical, and social conditions under which these manifestations were formed and developed. Because of its geographical position, Macedonia was one of the areas of the old Ottoman Empire wherein the old feudal arrangements lasted longest, and it was also the last to adopt relationships resultant on modern production, thus its folklore was least affected. Other factors have held a share in influencing Macedonian dance through its folklore such as historical and geo-political features.

In the central Balkan area, Macedonia gravitates toward the Mediterranean area, yet has also been influenced by surrounding areas as well – Alexander's Empire; the Bogumils; invasions and social and political changes of Slavic origin. Additionally, non-Slavs such as the Huns, Tartars, Goths, Avars, Crusaders, Normans, and finally the Turks, all overran the lands of the Macedonian peoples. All of them also, both Slavs and non-Slavs, left their marks and traces of their influences that have been found in the life, customs, and work of the people. All left very definite contributions to the artistic forms of Macedonian folklore, dance, music, and arts.

Almost every part of any costume has some symbolic significance. Every step and movement of a dance seems to depict some part of a story in Macedonian lore. In many lands, the people fall under the influences of, and adopt the customs of, their conquerors. Macedonia was influenced, but did not assimilate, the influences, perhaps there were so many, and it was more that the reverse was true.

It is safe to say that a Macedonian characteristic was a resistance to alien cultures, except that which was felt to be advantageously adapted as a new part of Macedonian life, local conditions, and taste. This perhaps explains the wide variety of elements to be found in the relatively compact area of Macedonia, and its so very rich and colorful dances, music, beautiful costumes, unique instruments, and friendly yet wary inhabitants.

DOCUMENTS

- Macedonia, a country and region.

- Macedonian Dances of Promhahi, an article.

Based on an article by Mane Čućov, "Jugoslovenska Knjiga," 1952.

Used with permission of the author.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, November 1976.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.