|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

When Serbians Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

I have arrived in the village of Dalj. My senses are reeling with impressions of peasant life here. As I walk along the broad Pannonian streets, a herd of white-haired swine cross my path while a flock of sheep and a dozen quacking geese brush against my legs. Horse-drawn sleighs, carrying peasants dressed in warm woolens and black lambs-wool hats, slide through the snow, bells jingling, scattering the pigs and geese in all directions.

I have arrived in the village of Dalj. My senses are reeling with impressions of peasant life here. As I walk along the broad Pannonian streets, a herd of white-haired swine cross my path while a flock of sheep and a dozen quacking geese brush against my legs. Horse-drawn sleighs, carrying peasants dressed in warm woolens and black lambs-wool hats, slide through the snow, bells jingling, scattering the pigs and geese in all directions.

I live in a typical village cottage with an earthen floor; the front door is about five feet high. As I am writing, Baba and Mama Ristić are cleaning the intestines of one of their pigs, slaughtered early this morning. They will make excellent sausages. Baba has placed a bowl of dark red goulash filled with steaming meat and vegetables on the table in front of me. The delicious red and green stuffed peppers, fresh-baked wheat bread, and heavy red wine have filled my senses. My host refills my glass with more delicious red wine and I cannot resist. I am no longer in this century . . .

As a young folklorist, visiting Yugoslavia for the first time in 1963, I wrote the above impressions of Dalj, a Serbian village on the Danube River, where the river borders the regions of Vojvodina and Slavonia. These impressions have remained with me through all my folklore adventures. This enchanting rural way of life has provided the setting for one of the most impressive dance traditions in Europe.

DANCE FOR ALL OCCASIONS

In the village no holiday, Saint's day, wedding, or other celebration could go without dancing. Almost every Sunday villagers gathered after church to dance, next to the church, in a field just outside the village, or in a central square near the community well. Fall and winter had Saturday evening dances too. Montenegro has stone terraces on the mountain slopes near the village. In South Serbia, in winter and on rainy days, dances were in barn-like structures known as čardak (literally, the enclosed porch on the first floor above the ground in a Turkish-style house). Traditionally, mastery of the dance was important. A man's standing in the community was often shown by his place in the dance line, and naturally the best dancers led. The best dancers might marry sooner, even if poor.

SATURDAY NIGHT IGRANKA

When I was in the villages south of Belgrade, everyone looked forward to the Saturday night dances called igranka (from igra, "to play" or "to dance").

The young people came to meet their friends and to distinguish themselves with the more difficult dance steps. I first saw this in the village of Pinosava, south of Belgrade not far from the landmark and park-area known as Avala. The local Kolo (literally "wheel", the common Serbian word for folk dance) is a form of the nearly universal Serbian dance known as U šest (literally "in six") or Moravac (after the Morava River). The tempo is slow and delicious, and the dance pattern, instead of going equally to the right and left, changes after two measures to the left, and travels right again.

The young people came to meet their friends and to distinguish themselves with the more difficult dance steps. I first saw this in the village of Pinosava, south of Belgrade not far from the landmark and park-area known as Avala. The local Kolo (literally "wheel", the common Serbian word for folk dance) is a form of the nearly universal Serbian dance known as U šest (literally "in six") or Moravac (after the Morava River). The tempo is slow and delicious, and the dance pattern, instead of going equally to the right and left, changes after two measures to the left, and travels right again.

It was a brisk dark autumn night. Lights strung over the village square added to and reflected the harvest moon. By the time I arrived, a few hundred people had already gathered and were dancing the Kolo. I had come forty minutes from Belgrade by the local bus. Imagine my delight to find all the young women of marrying age dressed in full regional costume from head to toe, including necklaces of dukati (large heavy gold coins that are family heirlooms and part of a girl's dowry). The young men were somewhat drab in West European dress, but an occasional old-timer had on bits and pieces of folk costume.

Then came a moment I'll never forget. "Crashing the party," a group of young men in old-fashioned Serbian costume burst onto the scene and immediately paid the musicians for the next dance. In their opanci (leather shoes open at the top with curly toes) and šarene čarape (multicolored socks), they dazzled everyone with fancy step work, double bounces and a surprise dip. Their version of the Pinosava U šest was a work of art. I later introduced it to American< folk dancers under the name "Pinosavka."

SABOR AND VAŠAR

An even better time for dancing than Sunday or Saturday was a sabor (church fair), or a vašar (village fair). These events could go on for days, with dancing from sunup to sundown. At a sabor, groups from many different villages, complete with their own musicians, would meet on the dance field in a swirl of sound and color. The best dancers vied with each other to lead the next Kkolo, and if there was dust, as there often was, it rose to cover the dancers, who in their enthusiasm never seemed to mind.

COMMUNITY PRIDE

Now and then they danced too. The very young were eager for the day when they too could join in. While tending the sheep they would ask the older girls to show them the steps, and after much practice, they would build up their courage and try their first dance. It was a moment of pride for everyone, especially for the youngster's family.

At the dance there might be traveling Rom (Cigani in Serbian), or traders, or soldiers coming home. Any new dances they would be eager to share. Names of dances such as Rumunjsko (Romanian), Bugarska (Bulgarian), and Čocek (probably from a Tukish word meaning "a dancing boy or girl") show a lively exchange from all over. Vranjanka, Čačanka and Užičko Kolo are named for three towns with strong dance traditions, Vranje, Čačak, and Užice. Banaćansko Kolo, Sremsko Kolo, and Bačko Kolo, all versions of the popular Malo Jolo (malo means "little") which has long been in the basic repertoire of American Kolo dancers, are named for the three regions of Vojvodina. The famous Montenegrin dance Zetsko Jolo, which seems like the flight of an eagle, is named for the 13th and 14th century Montenegrin kingdom Zeta. These dances are still done today. Some can be seen in the 1948 folklore film "Jugoslavenski Narodni Plesovi" ("Yugoslav Folk Dances") which I was able to rescue.

SLAVA (Patron Saint's day)

On a smaller scale, but equally important today, is the celebration of "Krsna Slava," a household holiday which honors the family patron saint. The excitement and planning begins several days in advance with the coming of the village priest to bless the water. Long hours are spent preparing a sumptuous feast of roast suckling pig, "sarma" (stuffed cabbage rolls), specialties of all kinds, and most important, the special "slava" bread stamped with the family's traditional slava seal.

On a smaller scale, but equally important today, is the celebration of "Krsna Slava," a household holiday which honors the family patron saint. The excitement and planning begins several days in advance with the coming of the village priest to bless the water. Long hours are spent preparing a sumptuous feast of roast suckling pig, "sarma" (stuffed cabbage rolls), specialties of all kinds, and most important, the special "slava" bread stamped with the family's traditional slava seal.

On the day of the slava the best linens and woven tapestries are displayed for the admiration of all the guests. After the guests arrive, the holy bread is blessed by the priest. Then the host ceremoniously breaks the bread which has been stamped, and shares it with his guests. He bids everyone to be seated while he, according to custom, remains standing at the head of the table throughout the feast. After the feast, plum brandy flows freely, and dancing, singing, and story-telling go on late into the night.

SVADBA (Wedding)

The most important family celebration is the wedding and its ceremonies. It is also the best time for dancing, since Serbian weddings are on a grand scale lasting for days and sometimes weeks with hundreds of guests in attendance. For the occasion the finest musicians are hired, and dancing is enjoyed to the accompaniment of accordion, frula, violin, and bass.

The most important family celebration is the wedding and its ceremonies. It is also the best time for dancing, since Serbian weddings are on a grand scale lasting for days and sometimes weeks with hundreds of guests in attendance. For the occasion the finest musicians are hired, and dancing is enjoyed to the accompaniment of accordion, frula, violin, and bass.

It is the groom and his family who are responsible for all the arrangements for the actual celebration. The stari svat (the groom's uncle on the mother's side) coordinates the entire production. The groom's brother, or best friend, serves as the dever (best man), and the most important guests are the kum and kuma who will be the god-parents of the young couple's children.

In some rural communities on the morning of the wedding, the groom and his party ride in caravan to "capture" the mlada or nevesta as the bride is called. In Šumadija, the groom must shoot an apple at the top of a ten-foot pole before the bride's family will open their gate to him. In South Serbia, he is met at the gate by the bride's family who will ask in feigned ignorance why he has come. He answers in poetry, explaining that he has come "for the little star which shines most brightly." Upon entry there is an exchange of toasts, the orchestras will start up and everyone joins in the dance for a short while. After a grand feast, the groom leaves with his bride for the wedding ceremony, accompanied all the while with songs and dancing.

TOWN DANCES

With the coming of King Peter Karadjordjević to the throne in 1903, an almost unbelievable blossoming of cultural activity took place in the Kingdom of Serbia, thanks to the real democracy brought to the country by King Peter the First.

With the coming of King Peter Karadjordjević to the throne in 1903, an almost unbelievable blossoming of cultural activity took place in the Kingdom of Serbia, thanks to the real democracy brought to the country by King Peter the First.

At this time, there grew up a type of bourgeois urban dance, reflecting the need to be "chic" as well as to bolster national pride. These dances of "national" character came about when various professional societies in the towns began to organize balls. They hired dance masters who created new Kolos, based on the more simple of the peasant dances. They were slightly arranged to have a more pleasing effect and symmetrical form and renamed with new titles, which had sentimental and nationalistic significance.

For example, the dance Srpkinja (Serbian woman) was the work of the Serbian composer, Isidor Bajić who incorporated the dance in his 1903 opera Prince Ivo of Semberia.

For example, the dance Srpkinja (Serbian woman) was the work of the Serbian composer, Isidor Bajić who incorporated the dance in his 1903 opera Prince Ivo of Semberia.

All the balls began with Kraljevo Kolo (the King's dance), which was led by the most eminent person present. This idea spread and such dances as Doktorsko (Doctor's), Trgovačko (Merchant's), Oficirsko (Officers), and Djačko (Student's) appeared. There were even dances named after political parties such as Radikalka, Liberalno Kolo, Demokratsko Kolo, and Radničko Kolo (Worker's dance).

Many dances were named after cities or a well-known part of town. A few which come to mind are: Beograđanka (girl from Belgrade), Dorčolka (named after a quarter in Beograd), Čukaričko Kolo (named after another quarter in Beograd along the Sava river), Niševljanka, Sarajevka, Zaječarka, and Bitoljka (composed in celebration of the liberation of Bitola from the Turks). In all, there were many dozens of such dances from this culturally rich period of Serbian history.

RITUAL DANCES

Rituals give us an insight into how dance was an inseparable part of the people's lives. They date back to a time when dancing was not only a question of social events and festivals, but was an expression of prayer and supernatural rite. Through the dance, a man could heal the sick, summon and dispel the forces of nature, bless the fields and the community, and bestow good fortune on himself and others. Ritual dances might be either the main expression of the occasion or simply an integral part. Sometimes they were performed by secret societies or special clubs of boys or girls who had banded together specifically for these rituals. Many of these rituals still survive today, either in original or changed form. Here are a few.

Dodole (rain dance)

Rites to ensure rain are not unknown in Serbia. On the road to Kosovo, at Toplica, there is a well known ritual dance, the "Dodole," performed in the dry summer months. Groups of little girls and perhaps some younger boys dressed up like girls, cover themselves with green leaves and flowers, and go from house to house singing ritual chants. The master of each house, as a symbolic gesture, pours water over the youngsters. When visiting each house, the dodole rain-maidens sing a chant:

Naša dodo Boga moli,

Da orosi sitna kiša,

Oj, dodo, oj dodole!

Mi idemo preko sela,

A kišica preko polja,

The dancers at Toplica tell an interesting story. They say that along the way to the river, as the rain-maidens go in pairs through the streets of the village, they steal a cross from the grave of an unknown soul; and from the house of an expectant mother, they steal a dinner table. They explain that this thievery is of course, proper and right. Reaching the river, they sit down around the stolen table in shallow water and eat specially prepared millet cakes, singing:

Od dva klasa, simil žita,

Od dva grozda, ćabar vina,

Oj, dodo, oj, dodole!

Finally at the end of the ritual, the dodole float the table with the cross on it, down the stream.

Pepper Dance

"How The Black Pepper Is Sown" is danced and sung in a comic solemnity in the villages near Leskovac by young men holding hands in a semi-circle. Holding a stick in his right hand, the leader conducts the dance and raps any awkward performer who does not mime properly the actions of sowing, gathering, pounding, and threading the peppers on strings to dry.

Called "Ovako se biber tuče" in Serbian, the dance depicts men pounding peppers first with their heels, then as a comic gesture with knees, elbows, heads and other imaginable parts of the body.

NADIGRAVANJE (competition dancing)

In Vojvodina an old dance which has lost much of its ritual significance is still performed today as a competition dance for young men. The men dance around knives stuck into the ground, vying with each other to see who can execute the same steps around the knifespirits had died, it was the custom that three men should approach the grave, one with a knife, another with a staff, and a third with a flask of wine. Linked together, the men would perform a symbolic dance showing their fear of approaching the grave with trembling movements. With the knife they would cut out the heart, and with the staff poke out both eyes; and then they would sprinkle the grave with red wine from the flask, thus exorcising the evil spirit.

PREVELIJ

In several Serbian villages on the Mlava River, "Prevelj" was a ritual dance enacted around a fire for the peace of dead souls. A large bonfire was built and each family who had had a recent death, would carry a log to this fire in dedication to their dead relative. The women were not usually allowed to be present at this event, but sometimes one woman would steal toward the fire and touch it with her spindle as a symbolic gesture. The dancing around the fire would get under way as soon as the musicians had first played a somber piece to which there was no dancing. The villagers would stand around the fire holding on to each other by their waistbands, while the mourners who did not dance, held lighted candles. The "kolovodja" (leader of the Kolo) held a long rod or staff in his right hand, and as soon as the fire died down, would call out to the line of dancers to jump over the fire. Those who wouldn't jump might be admonished by means of his large staff. Today the custom of jumping over the fire is largely dying out, though dancing around bonfires is still popular.

LAZAR

The week before Easter, Serbians living near Sredska celebrate Lazarus Saturday. A group of six girls, one of whom masquerades as Lazar (Lazarus), and another as Lazarka (the female equivalent), go from house to house singing and dancing. The girl who is Lazar wears a man's white shirt and a man's hat decorated with flowers. In his hands "he" carries a staff or sometimes an umbrella. The Lazarka wears a necklace of golden coins, and on her head, money, greens, and garlic to scare away evil spirits. The girls carry two baskets; in one they collect beans, in the other, eggs. After dancing in front of each house, they sing songs to bless the head of each houseÂhold, the house itself, any young boys or girls in the family ready for marriage, the livestock, and of course, the bees.

Za kuću (For the household)

Dobro jutro u kuću!

Ovde kuća bogata,

Tu se braća čuvaju,

Vedrom pare mereju,

Sad dukati zborea.

Za junaka (momka) (For a young man)

Ovde junak nešenjet!

Što ga majka ne ženi,

Što ga tatko ne ženi?

Nigde lika ne nađe,

Bela lika jaglika,

Crno-oko devojko.

POKLADE (Mardi Gras)

The months of January and February are the time of carnival throughout the country. Dancers appear wearing fantastic masks, sometimes more than six feet tall, decorated at the top with bird wings and feathers, heads of animals, as well as mirrors and colored streamers. Covered with sheep skins and armed with long clubs and wooden swords, they leap and jump to the deafening sound of drums and the cattle bells on their belts. In some areas the men blacken their faces and wear women's overdresses to perform these carnival dances that drive out evil winter demons and ensure health and good crops.

In some ways the carnival custom of Serbia is the most spectacular and colorful of all the ritual dance events. Performed mainly during the week before Lent, the festival in its entirety may last for a good part of February, beginning sometimes as early as January.

It is interesting to note that remnants of this fascinating custom of carnival dancing can still be found in Greece and Bulgaria and surprisingly in England's Morris Dancing, Germany's Fasching, and France's Mardi Gras.

KOLEDARI (carolers)

Around Christmas and New Year's the old Slavic Koleda is celebrated, each village in its particular way. On Christmas Eve, groups of young men sometimes visit from house to house. In Kosovo the "dedica" (grandpa), as the chief of the New Year's visitors is called, carries a plowshare and a hank of yarn and wears a bell below his knee. The leader of the Kolo carries a large staff and the dancers, treading through the deep snow, perform a different repertoire of songs and dances for each house. Near Leskovac where the Koledari wear masks, the dedica conjures up fertility by poking the fire and saying, "Let's bake bread, fry bacon, and roast a chicken."

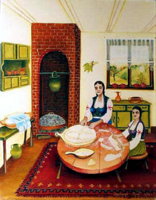

PRELO (spinning bee)

In the villages around Pirot, Serbia, women gather in the fall evenings to build a huge bonfire in front of one of their homes. Clustered around the warmth of the fire, they spin their wool, singing songs to accompany their work. The work and singing last late into the night. The custom is called "sedeljka" (spinning bee). Sometimes groups of boys crash the parties, but they do not participate in the work or in the singing. Bringing with them musicians to play for the Kolo, they dance with the girls and generally just cut up, sometimes even jumping over the fire. In the moonlight the singing and dancing around the fire create an enchanting impression in the chilling fall nights.

In the Šumadija region of Serbia, the "prelo" (spinning bee) is an opportunity for the boys to meet the eligible girls. While the girls spin and chatter, they eagerly anticipate the coming of the boys. They know when they have arrived by the sound of low voices in the shadows behind them; then the boys and girls tease one another, joke and sing songs, while the mothers or married women watch the proceedings. In some villages the girls like to compose special poetic verses for these parties:

Ide Stojan od oranje,

Bela Rada od belenje,

Sretoše se uz prolazu,

Ljubeše se uz obrazu.

Dok stajaše, dok dumaše,

Konja noge zaboleše

A kobilka lastar pušti,

Ajde, Rado, doma da idemo.

THE TIMELESS MOMENT

While years pass, timeless things are unchanged. After World War II, the Communist government took an interest, and State-sponsored performing troupes arose. Stage choreography came to have a large influence on the U.S. folkdance movement. With all these changes, one thing has remained certain. In country villages, and in emigrant communities from Australia to America, Serbs still love to dance.

DOCUMENTS

- Balkans, a region.

- Dennis Boxell, an article.

- Serbia, a country.

- Yugoslavia, a former country.

From Dennis Boxell's website

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.