|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Arranged Folklore

YouTubes illustrating or amplifying the topic discussed are

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

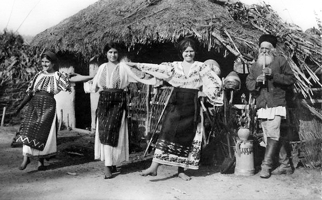

In South Eastern Europe before World War II, few people other than obscure academics, took any notice of folk dances. They were the cultural expression of 'backward' peasants; ill-educated, rural, superstitious, isolated, tradition-bound impediments to the catching-up these nations had to do to join the rapidly-changing, citified, mechanized, interconnected 'modern' world.

Of course the peasants themselves didn't see it that way. In the 20 years since World War I there had been lots of changes – education had become more common, though elders weren't convinced it was worthwhile; some families were generating surpluses, creating opportunities for improving their homesteads, having fancier costumes, better food, people were travelling outside the village, money was becoming available to buy what couldn't be made. By and large, life was improving; changing, but not enough to threaten the existing order – the supremacy of the family unit and traditional values.

One's personal identity was as part of a particular family and village and their reputations. It was not one's job or hobbies or tastes or religion or citizenship that mattered – it was who was one's parents and children, and in what village one lived. Within that traditional society dance played a central role. Everyone knew how to dance, and they danced at least once a week. The Sunday gathering was the chance for all villagers to get out of their homes or to come in from the fields and pastures, find out what each other was up to, barter, court or flirt or size up potential mates for themselves or their children, tell stories, have picnics, and to dance together. Like everything else in the culture, dancing came from tradition. Songs and dances were passed down from generation to generation, as was the village way of dancing – its 'styling.'

One's personal identity was as part of a particular family and village and their reputations. It was not one's job or hobbies or tastes or religion or citizenship that mattered – it was who was one's parents and children, and in what village one lived. Within that traditional society dance played a central role. Everyone knew how to dance, and they danced at least once a week. The Sunday gathering was the chance for all villagers to get out of their homes or to come in from the fields and pastures, find out what each other was up to, barter, court or flirt or size up potential mates for themselves or their children, tell stories, have picnics, and to dance together. Like everything else in the culture, dancing came from tradition. Songs and dances were passed down from generation to generation, as was the village way of dancing – its 'styling.'

It is important to understand that in a traditional village one didn't 'do' dances, one danced! The difference is significant. When one 'does' a dance, it is the dance – the choreography, the combination of music and footwork – that is important. The dance is a thing, a routine that has rules specific to itself. One cannot 'do' a čačak unless one has a particular rhythm and tempo and footwork pattern. Doing a dance is a matter of mechanics. Those mechanics are learned when one is a child, by watching and imitating adults or older kids until you get it right. In many villages, a child was not allowed to participate in the dance line until he or she could demonstrate that they could 'do' the dance.

However, when one dances, it is the feelings that are important. It is the feelings generated by the social occasion, be it a wedding, baptism, Saint's festival, village reunion, or regular Sunday dance. It is the interaction of musician and dancer, of dancer and other dancers, of dancer and the meaning of the song lyrics, or mood of the music. How one reacts to these stimuli is also influenced by tradition – whether the dancers' feelings and movements are appropriate for their age, gender, status.

During a typical village festivity, the dances one 'did' were few and long (by recreational folk dance standards) – 10 minutes or more. One didn't need to 'do' many dances because because what one 'did' was merely the structure to enable the real purpose, which was to dance. The same dance could be 'done' several times at an event, because the dance context was different each time. The music was necessarily live – there were no records or sound systems. Often, singing was the only music – singing by the dancers themselves or people standing by, or by leader-then-others in a call-and-response sequence. Songs had multiple verses, told stories that gradually unfolded verse after verse. When there were musicians, they played medleys of songs or simply riffs or constant improvisations on a melody. The dancers never knew what was coming next, so they were actively engaged in listening to the music and gaining inspiration from it.

Quoting from Traditional Dance in Greek Culture by Yvonne Hunt: "There has traditionally been a strong relationship between the dancer and the music and/or musicians. One frequently gets his kéfi (his gaiety or good mood) from the other. A good dancer will inspire the musicians to play their best, good music will bring out the best in a dancer ... . The lyra player watches the dancers closely and is able to know from certain preparatory movements, when the dancers are approaching a semi-cadence. A good lyra player is able to make a musical cadence exactly coincide with the final leap of the dancers. This interaction between the two is extremely important. Without this inspiration from the music, many will not dance. Since the dance is not just a series of steps to be gotten through at any particular moment but an extension of one's self, the importance of this give and take between music and dancer should be readily understood."

The result can be a dance experience of a nearly spiritual intensity. Richard Crum, on his first visit to the Balkans in 1952, said "I witnessed a non-staged dance in a market place in Sarajevo." When in later years American folk dancers would ask him, "What approach do you use when you see a non-staged dance and you want to join it?" he would recall this experience and reply, "It will not even occur to you to get into that circle. And, belive me, when you're faced with a real dance ... you will not even think of joining it ... When I saw Trusa on Baščaršija, I realized I did not belong there. Then I realized I am seeing something here that is very different from all the other folk dancing I have seen." [from Balkan Fascination by Mirjana Laušević, 2007, Oxford Univ. Press]

Where do traditional dances come from?

Where do traditional dances come from?

It's almost impossible to trace the starting point of a traditional dance, but it's relatively easy to surmise that very few were 'created' full-blown from some folk genius's imagination. A country like Greece or Romania has thousands of folk dances, but a closer look shows most are regional variations of one another. Many have similar footwork done to different songs or rhythms. Many are similar to dances done across a border from another country that used to be inside the same region. Many are the result of one population moving or being forced to move to a distant locale, where their traditions blended with those of their newfound neighbours. Those of you who have digested my articles on the Taproot Dance, The Taproot Family, and Uneven Walking know that most Balkan dances are variations, combinations or elaborations of these two basic patterns, which date back hundreds, even thousands of years.

Dances are often influenced by the meters used in the poetry of songs – there are far more songs than dances, but again, tradition determines that a given culture has only a few types of meters used in most songs. One doesn't need many metric forms – each can express an infinite number of ideas based on the richness of language. Also, one doesn't need many dance forms – the richness and variety comes from the unique social situation of each performance – from the variety of dancing when one 'does a dance.' In a pre-literate society, traditions are passed down from generation to generation – experience is valued more highly than creativity. Traditional dances are seldom created. Like other aspects of traditional life, traditional dances are the products of gradual evolution.

After World War II, Southeastern European countries excepting Greece and Turkey were taken over by Communist regimes controlled by the Soviet Union. It is one of the great ironies of history that Communism the ideology was conceived as a reaction and solution to the ills of urban industrial societies, but was practiced on rural agrarian ones. In order to put the ideology of a worker-run industrial society into practice, one must first have a society of workers – wage employees – and there were very few of these in Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania or Yugoslavia. So the first task of the Communist regimes was to transform scattered landowning self-employed farmers into landless factory employees concentrated in cities, dependent on the state. Even food production was industrialized by confiscating peasant's small holdings and aggregating them into factory farms.

After World War II, Southeastern European countries excepting Greece and Turkey were taken over by Communist regimes controlled by the Soviet Union. It is one of the great ironies of history that Communism the ideology was conceived as a reaction and solution to the ills of urban industrial societies, but was practiced on rural agrarian ones. In order to put the ideology of a worker-run industrial society into practice, one must first have a society of workers – wage employees – and there were very few of these in Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania or Yugoslavia. So the first task of the Communist regimes was to transform scattered landowning self-employed farmers into landless factory employees concentrated in cities, dependent on the state. Even food production was industrialized by confiscating peasant's small holdings and aggregating them into factory farms.

The regimes recognized that they needed the co-operation and loyalty of the people for drastic social change to succeed, so, again taking cues from the Soviet Union, they glorified 'the people' – the little guys they were purporting to represent – by idealizing 'folk' culture, the supposed wellspring of the state's values, and by lavishly supporting folk arts. However, with the support came an agenda – one got the support if one participated according to the state's idea of what folk arts should be. The state considered itself to be scientific and forward-looking, whereas religion and much folklore was considered 'backward' and 'unscientific.' So folk arts were stripped of religious connotations unless they were used to ridicule backward ways of the past.

Minorities like Roma or Turkish-speakers, or Muslims were not represented – the ideal citizen was white and spoke the majority language. All were to form one seamless whole. In order to give to all equally, the state required equal participation – no 'mistresses' to divert energy and loyalty, like another language or a religion. Emphasis was on the masses, not the individual. One was supposed to sacrifice one's present comforts and identities in order to build a better future for all

Folk dancing in the Balkans was first destroyed by the state's breaking up of family farms and shipping families off to poorly-built high-rises in cities, where people from different regional traditions were mixed indiscriminately, or by separating families, sending individual members to schools and factories in different places according to the needs of the state. The authority of tradition and the family was replaced with the authority of the state.

Then dance culture was rebuilt along the top-down lines of the Soviet Moyseyev model. The idea was to show the locals what could be achieved by embracing the values of the state, and, perhaps more importantly, show the world what this new ideology could achieve. In Bulgaria, for instance, achievement took the form of the Filip Kutev ensemble. The state provided the funds and appointed classically-trained Party loyalist Kutev its director. He wrote the music, trained the orchestra and choir, supervised the choreography – ran the show.

To create a state dance company on the level of Moyiseyev or Khoutev, one needs an entire pyramid of ground-up infrastructure, just as one needs a fan base for a sport and several lower layers of instruction and teams, as well as professional-level study of the sport, to produce a world-class sports team.

The study of folk dancing begins with field researchers collecting folk songs, either on paper notation, or a field recording. A village song was likely sung a capella, that is, without instrumental accompaniment, often with no harmony, and may or may not have been sung at dances. Dances were recorded on paper, but also filmed in the field, often without the accompanying music, or dancers were brought into a studio to be filmed. Scholars were hired to categorize and analyze movements, study regional differences, etc; archives were cataloged and stored in state facilities, – very scientific!

Amateur ensembles were formed in towns, schools, and factories. Exhibitions and competitions were sponsored, and the best musicians and dancers were funneled upstream to the academies. The talent flowed both ways, with new ideas in presentation filtering downward to amateur companies looking to spice up their programs and help win competitions, which could result in more state funding.

Academies of folk arts, other academies of folk music and/or dance were created and supported. In them, choreographers were trained to blend simple native folk dances into complementary suites that guided the audience through a series of climactic moments designed to produce exhilaration. Composers were trained to produce music to complement and drive the choreographies. Concert halls were built, festivals sponsored. Folk symphonies, films, painting exhibitions, and operas were commissioned.

Radio [before there was television] played a pivotal part in advancing the state's role as the benevolent patron of folk arts. Radio stations formed their own 'orchestras' – combining native folk instruments in a number and variety never conceived of in "the village," to create orchestras capable of rivaling Western bourgeois classical symphonies. Composers classically-trained with knowledge of sophisticated Western chords and compositional techniques unknown to the Bulgarian peasant, modified folk tunes and commissioned new 'folk' instruments similar to classical symphony instruments, to fully exploit the orchestra's possibilities, thus raising a simple song to the level of 'Art.' Recordings were made of these performances, broadcast, and turned into records to be sold locally and abroad. Most of the musicians employed were originally villagers who couldn't read music, the instruments themselves represented various regions far enough apart so as to be rarely combined with each other, yet these musicians learned to play together in a highly disciplined manner which required years of training and careful orchestration. Choirs were created similarly – of a size and complexity of harmonic construction undreamed of in the 'village.'

Timothy Rice, in his landmark, detailed book on the transformation of traditional folk culture as experienced by a family of musicians in Bulgaria, May It Fill Your Soul, 1994, University of Chicago Press, wrote "The state's goals for folk music arrangements in the Communist era were certainly lofty ones: to improve the aesthetic appreciation of the rural audience; to sensitize the urban audience to its national patrimony; and, by creating a shared aesthetic experience, to fuse the two classes into a "new society" capable of 'building communism.' Explaining the first goal, Kosta Kolev, director of the folk orchestra at Radio Sophia during Kostadin Varimezov's [the subject of the book-DB] tenure, said, 'We wanted to make folklore grow to to serve contemporary life. We tried to create music that would raise the taste of the people. These arrangements were a step toward art, so that [village] people could eventually listen to Bach, Mozart, and Shostakovich.' Goals such as these transcended mere entertainment; they privileged urban over rural practice as more 'artistic' [hudozhestveno], and they contained a fundamental optimism that the Party could remold people and their tastes to conform to their intellectual, social, and political goals; in fact, it symbolized the backwardness they were determined to eradicate. Only in the hands of the 'folk/peoples artists' [narodni artisti] playing artistic arrangements could folk music have value for the new state... .

With these goals in mind, the composers 'commanded' the musicians and controlled their output. They even directed and influenced the the means of production and distribution; the ensembles, the radio, the record company. Like Bulgaria's fledgling industries, the communications media gave consumers an annual quota of goods designed with the state's, rather than the public's, needs in mind."

Rice then goes on to describe how Kostadin Varimezov had to adapt his traditional playing techniques to the challenging demands of a radio 'folk orchestra.' Well worth the read for musicians wanting to understand the techniques of 'arranged folklore.'

To use an American analogy, an 'arranged folklore' composition and recording such as the music for Brestaška râčenica may have as much 'folk' content as Turkey in the Straw performed by the New York City Ballet accompanied by the Boston Pops Orchestra. The urban audience may well have enjoyed it, but few country folk would be as appreciative.

Quoting Rice again: "One arranger, Lyuben Tachev... was adamant that Bulgarians didn't like arranged folk music: 'Even the composers don't listen to their own work after it is recorded.' His cynicism about composers began when he...trained at the Sofia Conservatory in the 1950's. As a village musician, he was struck by how few of his fellow students, who would later become influential folk music arrangers for the Radio and various ensembles, were from the villages, and what little connection to folk music they seemed to have."

Apparently there was a similar situation in dance academies. Although Kutev originally recruited the best dancers from villages, once the academies were up and running, most students were from the cities (one needed a background in classical ballet to gain admission), had little knowledge or appreciation of village practices, and followed their instructors who believed that by 'arranging' dances they were elevating their artistic value.

What composers did to Balkan music, choreographers did to Balkan dance. Kutev and their like were producing shows for urban audiences used to seeing ballet, musicals, modern dance, etc. They knew they had to put on a good show or no one would pay to watch. Igor Moiseyev showed how to make it work – large, synchronized, precision-drilled chorus lines that broke into ever-changing patterns, bright matching costumes in primary colors, young, smiling vigorous dancers, choreography that told stories using mime techniques. Moiseyev always claimed that his dances were based on thorough research in the folklore of a region, but he neglected to add that his research was for 'inspiration' only, and was seldom employed in his choreographies.

One key difference between Moiseyev and village practice was that in the village, people danced for their own enjoyment – for emotional release. There was no attempt to make a dance line look uniform – it would have interfered with each individual's spirit of self-expression. With Moiseyev the opposite prevailed. He recognized an audience liked to see a stage full of dancers, but would be confused by multiple dancers doing multiple things. A dancer in a Troupe had to suppress his or her emotions; be disciplined to achieve uniformity with the chorus line. Emotions were pasted-on smiles – all the time. A line of dancers doing the same thing made it easier to see what was being done, and there was something satisfying about seeing 40 men or women acting simultaneously. Of course it also fit into Soviet ideology whereby it's the masses that are important, not the individual. Western audiences were enchanted, national governments were proud, few seemed to care that what they saw bore almost no resemblance to 'village' folk dance practices.

Other companies followed suit, including non-Communist countries such as Greece and Turkey. Not all completely abandoned village practices. Greece, not under Communist ideology, managed to produce a dance troupe that adheres as closely to village practices as the limitations of a staged performance allows. Croatia, under Communist control, managed to avoid major distortions of village practices, and Hungary successfully wrested control of its program from bureaucrats and returned it to ethnologists. But those are the exceptions proving the rule.

At its peak, the folk dance industry in the Balkans formed a significant part of the state's economy, employing scores of people. Certainly, support for the folk arts (and the arts in general) received far greater state attention in the Balkans than in the United States of America. This support created an ever-increasing demand for folk dance 'product' – recordings, choreographies, performing groups, musicians, etc. The academies were churning out graduates eager to get employment with a large or not-so-large company. According to Rice's book, composers were paid for arranging a folk song, thus many arrangements were produced in the hopes of being recorded. Being 'folk' songs, no one thought to pay the person who brought the song to the attention of the composer. Todor, Kostadin Varimezov's wife, who had a vast repertoire of folk songs in her memory bank, often freely shared the songs with others who then arranged or sang them for pay without giving credit (and therefore money) to the song's source. Pocketing the extra money due to others incentivized composers to create more arrangements and recordings. I imagine a similar system was in place for choreographers.

When the folk dance industry began in the Balkans, resources were focused on researching and cataloging a nation's songs and dances, then on incorporating them into routines for the performing groups. As more people became involved, more songs and dances were discovered until most were archived. Because composers and choreographers were trained (using the Russian model) to consider themselves artists rather than conservators, folk songs and dances were considered raw material from which to make art. By coincidence, most of the composers and choreographers trained in the conservatories came from the cities, had little experience with, and even less respect for peasant culture. Choreographers, their urban 'artist' biases unchallenged, had no qualms about 'arranging' and 'improving' folklore. Thus, dances that were fairly simple and repetitive in the village acquired many complex 'variations' when seen on stage – variations that over time took on the aura of authentic village moves.

Villagers' reaction to the transformation

Villagers' reaction to the transformation

How did Bulgarian villagers react to hearing their traditional music filtered through the 'elevated' tastes of the intelligentsia? Rice again: "The anecdotes of people rejecting the composers' arrangements of narodna muzika are legion. Kutev's choreographer, Kiril Dzhenev, told me about a man coming up after an early concert in the 1950's and saying, 'You sang really well. Now sing us a real folk song.' One musician active in the 1950's told me of a saying in those days about 'arranged folklore' that illustrates the antipathy many people felt towards it: 'A wine that has passed through Vinprom [the state winery], and a folk song that has passed through Filip Kutev – screw 'em!' While the state had good intentions to produce a new high-quality life, in fact what it produced was often shoddy or not what the people wanted, whether in wine, housing, jobs, or music.

In addition to added harmonies, which displeased many village listeners, the truncated song texts, shortened for radio broadcast and records, annoyed them as well. As Todora Varimezov said 'They cut out stuff. And the most interesting part of the songs can't be said, that is, you start at the beginning, but the most interesting part is later on. They give three or four couplets. Sometimes you can't understand what it is about. They just get started and there is nothing.' From the point of view of the villagers, who know the tradition the best, the shortening of songs to fit producers' concepts of the limited attention spans of modern, urban audiences was one of the most profound alterations of the tradition. Whereas at a sedyanka, dance, or at home around a table, a song could 'have no end', as Todora once said, radio producers assumed that their audience needed constant musical variety and was not interested in the texts. While this may have been true of the new audience of urban dwellers, the villagers were bored by precisely the absence of the content they remembered was there. In this case, as in so many others, the aesthetics of the literati and their assumptions about the worth of folk song won out over the values of the villagers.

The musicians heard the criticism of their work as well; even the simplest arrangements offended most villagers. One of Kostadin Varimezov's relatives complained to him of the orchestral accompaniments 'It's as if someone grabbed you and pinched you continuously.' Varimezov continued, 'People say they like my playing, but they don't like the instruments that howl around me.' For the villagers' taste, there were, as the Emperor supposedly said of one of Mozart's compositions, 'too many notes.'

"Arranged Folklore" – creating a 'folk dance'

"Arranged Folklore" – creating a 'folk dance'

Tim Rice again " ... although many traditional village contexts died after World War II, its traditions lived during the Communist period as an instrument of the state, resurrected from their death after collectivization of the land and secularization of their belief structure. Organized, prettified and cleaned up, village forms and practices were given back to the people as a symbol of national pride ... This new "tradition" produced another kind of recording ... not memories of village music but but what Bulgarians called "arranged folklore" [obraboten folklor]" "Arranged folklore" was the process used to transform village dance practices to make them suitable for an audience watching a performance on a stage, and to conform to the state's idea of how it wanted to portray 'the people.' Dancing, the feelings of individual dancers as they danced, was difficult to see by an audience, but the mechanics of a dance – the form and footwork, were not, so the mechanics were emphasized and exaggerated. Choreographers learned to combine variations from several villages into one dance, or to combine two or three dances into one, or to pick the most interesting bits from several dances to make one. The product of any of these machinations could still be claimed to be an 'authentic' folk dance because it used exclusively 'authentic' material. Likewise, music could be re-arranged, shortened, orchestrated with added or altered harmonic structure, or combined into medleys. Finally, a choreographer could claim that because he or she was seeped in traditional culture [due to his academic studies and visits to villages or viewing of archived material] he or she could find a pre-recorded song and compose steps to match musical sequences, based on his or her knowledge. Matching steps to musical sequences was critical to a dance's acceptance by a performing group, for that is exactly what a performing group needs. All dancers must dance in unison to achieve a good visual effect, and they rely on musical cues to keep them in time.

Once one has created a unique choreography to a specific recording, one has a distinct package that needs a distinct name. The choreographer may have incorporated a step as part of his arrangement that's specific to a particular village. Or maybe the song is associated with the village. Usually, but not always, the dance's name has some relationship to the package's contents. What is most likely is that this song/dance package was never danced in a 'village' situation using this choreography – it needs the arrangement of a specific recording to work. Thus dances were created and performed and presented to foreign audiences as 'authentic' folk dances even though they were never danced 'authentically' by villagers.

By the 1960's, it was becoming difficult for even determined folk dance researchers to encounter folk dance in its native habitat. However the state systems were booming – amateur state-sponsored folk dance groups were everywhere, performing often. The best of them were allowed to travel abroad – a coveted perk. There was a demand for dances that looked good on a stage, and a supply of state-trained choreographers more than willing to turn folk 'material' into "arranged folklore."

As stated before, when one dances, the choreography isn't important – it's merely the vehicle for dancing – the spontaneous interaction of dancer and environment that constantly varies. When one 'does a dance' the opposite is true. One is recreating a choreography created for a specific purpose, timed to a specific piece of music. One is not inspired to 'do a dance' more than once in an evening. Thus to fill an evening dance program, of 'doing dances,' more 'arranged folklore' is required than in an evening of dancing to live music. It's a virtuous cycle for choreographers. Over time, 'arranged folklore' dances began to outnumber village dances, but as most villagers were now scattered in cities, few villagers remained to object.

A quote from the preface to Greek Folk Dances by Ricky Holden and Mary Vouras, 1965, published by Folkraft-Europe: " ... while the performing folklore Troupes do a wonderful job of reviving interest in native dances among the people of Greece, we note with surprise what is happening to some of the best Troupe dancers. These dancers, who can shift style easily and properly from an Island Bállos to a Pontic Serra and back again, are becoming so routine-minded they have lost the ability to ad-lib. They are concentrating on dances instead of dancing. It may even go so far that dancers of routines return to chide the original villagers for not doing their own dances correctly! Well, we may at least caution those who learn from the present book to beware of this trap."

Westerners discover Balkan Dancing

Westerners discover Balkan Dancing

Ironically, it was the music and dances of the Filip Kutev Ensemble that first got me interested in Balkan dance. I have read that seeing Moiseyev and/or hearing Kutev was the catalyst for many a budding folk dancer. The assumptions of Bulgarian radio producers may have been criticized by Bulgarian villagers, but they were dead-on about me, and I believe many of my compatriots. I was born in the United States in 1946, grew up seldom hearing live music, but constantly listening to pop radio playing three-minute records. My ear for music was trained for a short attention span, constant variety and few lyrics. I had some background listening to Classical music – enough to find the dissonances, complex harmonies, and unusual instrumental combinations of Kutev intriguing. And of course there were those rhythms! Likewise my eye was trained to see flashy dance routines in movies and on television, where the subtleties of inner enjoyment didn't register. The music/costume/dance combination was very exotic and I experienced it at a time in my life when I was questioning the values of my own culture; open to alternatives. Because very little information about Balkan culture was available to us Westerners, we were free to fantasize our own scenarios, and to believe that what we saw on the stage was a relatively accurate representation of village dancing.

To quote Anthony Shay in his book Choreographing Politics, Wesleyan Univ. Press, 2002: "It would be almost impossible for anyone not present in the audiences of the first visit of the Moiseyev Dance Company to the United States in 1958 to understand the impact of those appearances ... All of the senses were overwhelmed by the perfectly precisioned, over-the-top acrobatic prowess of a hundred brilliantly costumed dancers accompanied by a specially designed symphony orchestra, which actually heightened the effect of the visual spectacle ... The unusually large crowds, which numbered in the hundreds of thousands, for the U.S. tour, were attracted partly by a foretaste of the company on "The Ed Sullivan Show," viewed by millions of American households, and partly by the illicit thrill of seeing actual Russians for the first time. At the height of the Cold War, many Americans did not realize that all Russians were not Communists ... Many in the audience wanted to verify for themselves whether, in fact, Russians, by which one meant Communists, had horns and tails!"

"Kolomania," as the first phase of Balkan fascination came to be known, arrived in the mid-1950's – just when the folk dance scene in the United States was transitioning from live to recorded music, couple to single dancing, Northern European to a more International focus. A new generation of college-age dancers was becoming involved – aided by the emergence of the American folk scene, soon to evolve into something more political. We were ripe for something different, but not too different. Balkan folk music, conveniently packaged into dances one could 'do' without having to be seeped enough in the culture to have to dance, became the dominant trend in folk dancing. It was fueled by the arrival of the Macedonian dance troupe Tanec and Serbian group KOLO, both in 1956, preparing the way for the triumph of Moiseyev in 1958.

Folk dancers soon tired of 'doing' the same simple dances going the rounds of clubs in the 1950's. A few pioneers like Dick Crum had been to the Balkans and brought back tales of a vigorous but fast disappearing village dance scene in Yugoslavia. Other dancers 'went over' and came back with some original observations and an understanding of traditional practices but most of us back home didn't have the time or dedication to modify our already solidifying habit of 'doing' dances, rather than learning how to dance. Besides there were very few musicians who could deliver a live music experience, and we felt more accomplished 'doing' a dance where we we were familiar with the record than groping around to live music we weren't familiar with. Instead, we wanted more dances to 'do.' Soon, it became standard practice in North America to expect to go to a workshop and be presented with a slew of new dances, each coordinated with a record of its own, and choosing the ones that most pleased us irregardless of how 'authentic' they were.

It was one of those convenient coincidences that Westerners' desire for Balkan dances we could 'do' happened at the same time that Balkan countries were being flooded with 'arranged folklore.' It made for easy pickings for dance instructors to come back with new material. One could visit one of the state dance companies or archives or radio ensembles and select material appropriate to home tastes. Soon, members of those companies realized an opportunity, came on a tour, and defected to the West, knowing there was a ready market for their material. Few here knew the difference between village dancing and 'arranged folklore,' and fewer still wanted or knew how to dance, but everyone, it seemed wanted to 'do' more dances!

That said, let me state that I like 'arranged folklore,' and I definitely consider it a Bulgarian art form. I readily acknowledge that I enjoy folk dance as an 'alternative reality' – a chance to step outside my own culture for awhile, assume a different persona, both physically and mentally, and effortlessly return, when it's over, to my comfortable routine. I appreciate the ease of 'doing' a dance when my folk dance club can't provide a live band so I can dance. I appreciate the awareness of traditional values in the choreography, the skill of execution, the highly stylized and uniquely Bulgarian or other ethnic sounds of the recorded music. I appreciate the great variety of music, moves, and rhythms available to an International Folk Dancer. I appreciate those instructors introducing these dances to us who try to accurately credit the dance's origin.

I admire instructors who have made a genuine effort to educate recreational folk dancers about how to distinguish the array of hybrid and genetically modified dances overwhelming our gardens from the simple, humble, sturdy stock languishing in the neglected corners, even as I admit to falling for the charms of the hybrids.

I do believe, however, that those who lead folk dance groups could make more of an effort to educate themselves and their members on the relative 'authenticity' of the dances in their repertoire. My experience is that few dancers can dance, partly because they don't even know that dancing is what traditional dances were for. They're not aware that a dance that is arranged for you to 'do' is likely not a village dance, but 'arranged folklore.' That means they're missing out on an opportunity to expand their horizons without having to learn MORE dances. They can simply learn which dances can be danced, and practice dancing.

What I find most offensive, however, is that we folk dancers blithely call anything from, say Romania a Romanian dance, without bothering to discover if anyone in Romania other than some performing group or a choreographer has ever danced it – whether it CAN be danced. Imagine going to an American dance class in Romania and discovering that all the dancers there call Yankee Doodle Dandy, The Rock 'n Roll Waltz, Stairway to Heaven, and Blame It on the Bossa Nova American folk dances because that's what they learned in class. Now imagine that same group performing those 'dances' in a festival of international dance – proudly showing their cosmopolitan nature by demonstrating their knowledge of American Folk Dance, and teaching them to their children. We might be amused, or we might be offended, but we certainly wouldn't respect the dancers for their knowledge. I spend a lot of time watching Balkan dancers on YouTubes dancing. Sometimes I've seen Balkan residents doing what they call American dances, and the results show almost as little knowledge of us as we have of them. They have fewer resources, however, with which to check the veracity of their leaders' claims. Remember when posting a dance of your group 'doing' a Bulgarian 'dance' that Bulgarians can just as easily see and judge you. It's good to know the difference between traditional dance and 'arranged folklore.'

From Don Buskirk's website, Folkdance Footnotes.

Used with permission.

This page © 2023 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.