|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Central Asian Music and Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

Central Asia: unknown, exotic, mysterious. Land of Marco Polo, the Silk Road, Samarkand and Bukhara, Gengis Khan and Tamarlane! All of this is Central Asia, and more.

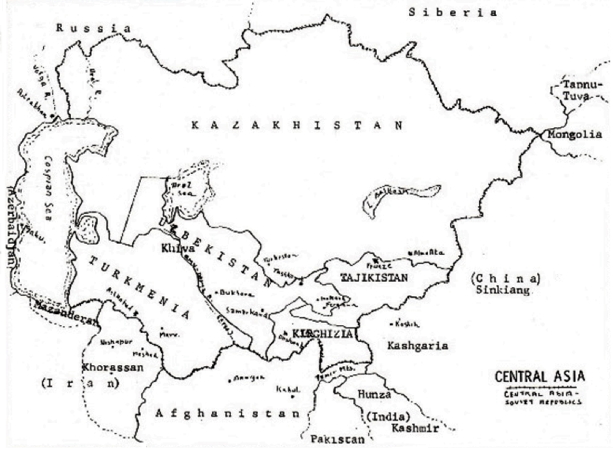

Like many vast geographical and historical, cultural and linguistic units, Central Asia is a concept. For purposes of this article, Central Asia encompasses the steppes, oases, deserts, and mountains south of Siberia and its forests, north of China (although including Sinkiang province and Mongolia), east of the Caspian Sea, and southwest into Khorasan (Iran), and north to the Himalayas. This then, includes Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenia, Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, and Sinkiang and Mongolia. It is land-locked, largely arid, so that the search for grass for the herds of the nomadic dwellers has been a major factor in the southerly and westward movements of these people toward the rich agricultural lands of China and Persia that characterized the centuries of history of this vast region, with repercussions as far as Europe1, Anatolia, and the Fertile Crescent.

|

The importance of this area is that it has historically been the bridge between the two ancient civilizations of the East – China and Persia – and through Persia, the Middle East, Byzantium, and the West. Central Asia was, in short, a cultural and intellectual offshoot of these two main civilizations.

"Over many centuries, the Central Asian caravan-trade followed a number of different routes but the most important were always those which linked China with the West. . . As for the urban elites, their culture was generally an extension of that of contemporary China or Iran and at least, in the south-west, it was the urban centers which acted as spearheads for the penetration of Muslim civilization into Central Asia. Almost down to the 20th century, the cities of Mawarannahr (Transoxiana) and the western part of Kashgaria (Sinkiang) remained cultural offshoots of Iran so that the traveller leaving Isfahan or Mashad for Bukhara or Yarkand would find upon reaching his destination, a way of life not altogether unfamiliar." (Hambly, 1969:7-10)

Central Asia is an area that has been the cultural and physical battleground between Iranian sedentary town and village dwellers and Turkic and Mongol nomads. This ancient theme runs through Iranian legend in the pre-Islamic stories of Iran and Turan, immortalized in Fidowski's Shahnameh. As Rome kept its watch on the Rhine, so Persia kept its watch on the Oxus.

If one can demonstrate an historical theme to this vast region, it is the build-up of group after group of Mongol and Turkic-speaking nomads, shamanistic and animistic, in religion, descending and pushing before them other only slightly less powerful nomads, who were brutally efficient warrior hordes, toward the vulnerable oasis cities to the south. Affecting even Byzantium and Rome, these hordes produced Gengis Khan, Attila, and Tamerlane. Before our own era, these nomadic groups were Iranians – Scythians and Sarmatians – but later, they were Turks and Mongols (a linguistic designation).

As these hordes pushed toward China and Persia, they destroyed or pillaged the small, local, often culturally distinguished and elegant cultures centered in the oasis towns of Shash (Tashkent), Samarqand, Ferghana, Marv, Nishapur, Ghazneh, Bamilyan, Khokand, Yarkand, etc.

The same nomads who destroyed these cultural centers often settled there, and using local Persian or Chinese administrators and artisans spared from the general massacres, began the process from the beginning.

The centuries-long domination of the nomads gradually ceased with the general use of rifles, the superiority of which allowed the Russians to begin their eastward expansion at the expense of the hitherto victorious steppe dwellers.

The intensive massacres of millions of Iranian-speaking people created vacuums in the urban and village areas and a racial and linguistic shift began in which Turkic-speaking Uzbeks and others settled.

In Marv, in present day Turkmenia for example:

"After Shah Murad's troops had sacked Marv they proceded to destroy the elaborate irrigation system of the Murghab River which had for so long given life to the oasis so that both the city itself and the surrounding countryside soon reverted to that desolate condition so eloquently described by 19th century travelers. The occupation of the oasis was followed by the systematic deportation of its Iranian inhabitants, who so glutted the slave-market of Bukhara that prices fell to a level unknown in living memory and by the close of the 18th century, the Iranian population of northern Khorasan had been replaced by Turkomans, even in the oases." (Hambly, 1969:181)

In Samarqand and Bukhara, however:

"From the 16th century onwards, Turks probably formed a majority in the racial composition of the population of Mawarannahr and it seems likely that there was also an increase in the proportion of nomads to sedentary cultivators or townsfolk. Iranian culture and the Persian language continued, however, to exercise a pervasive influence on the ruling elite and formed quite early in the 17th century, Uzbek clans which had entered Mawarannahr more than a century before as nomadic cattle-breeders to settle in the oases as cultivators and even city-dwellers, apparently assimilating themselves without undue difficulty with the existing sedentary population, whether Turkish or Iranian (Tajik). In cities like Bukhara, there continued down to the 19th century, a prevalence of Iranian racial types – descended from the ancient inhabitants of the oases, reinforced by generations of captives from Iran, prisoners-of-war or the victims of slave-raids." (Hambly, 1969:172-3)

Upon my visit to Samarqand and Bukhara in 1976, the majority of the population spoke Tajik, a language so close to Persian that the difference was no more than that of British and American English. Because these two cities are in present-day Uzbekistan, the populations are probably tri-lingual, speaking Uzbek and Russian as well.

A third historial theme is the religious issue of the establishment of Shi'ism as the state religion of Iran in the 16th century under the Saffavids. This brought cultural exchange to an almost complete halt. The cultural decline was exacerbated by an accompanying economic one because of unsettled internal conditions and the opening and expansion of sea trade between Asia and the West, from which land-locked Central Asia was excluded.

"Even though there was no complete barrier against the spread of Persian culture into Central Asia in the following centuries, the difference of faith obstructed its diffusion. . . There is certainly justification for seeing this as largely responsible for the marked decline of the Persian language in Transoxania, which allowed Turkish, henceforward so to speak, the 'Sunni language'. . . This shift of language and the weakening of links with Persian culture brought the development of the country down, very gradually, from the high level that had been ensured by the common cultural development of the Middle Ages." (Cambridge History of Islam,col. I, 1970:468)

As Hambly sums up,

"By barring Uzbek expansion south of the Amu-Darya . . . the Safavids effectively isolated Mawarannahr from the rest of the Islamic world, an isolation which was to blight her intellectual and cultural life down to the close of the 19th century." (Hambly, 1969:164)

All of these themes of history are exceedingly important if one is to understand the dynamics of dancing and music in Central Asia, and the cultural conditions under which these art forms were developed.

While Afghanistan contains large Uzbek and Tajik populations, as well as Persians, Kazakhs, Turkomans, etc., the largest majority is the Pashtun (Pakhtun, Pathan) whose dance and music traditions have not been well researched to date.

The Soviet Republics are named for the majority populations, but there are many Tajiks in Uzbekistan and Kirghizia; Turkomans in Iranian Khorasan and Afghanistan; Kirgiz in Tajikistan, etc.

There is a good deal of confusion regarding the origins of the Turkic-speaking groups: Uzbek, Turkoman, Kazakh, Kirgiz, plus the less numerous Kara-Kalpaks, Uyghura, etc. The Uzbeks speak Chagatai Turkish which is one of the Eastern Turkic dialects used during the development of the Ghengis (Changiz) Khanate, utilized as a spoken language under the Temurids (descendants of Tamerlane), and brought to flower as a literary language under the Shaybanid rulers of the Uzbek Khanate.

The Kazakhs, Krigiz, and Uzbeks are linguistically related. In attempting to trace their origins, Hambly remarks:

"Muhammad Shayband for many years led the life of a freebooter before assembling a band of followers at whose head he invaded Mawarannahr in 1500, occupying Bukhara and Samarqand. He founded on the ruins of the Timurid empire, the last great empire of Turkestan – the Uzbek Khanate. . . The migration of the Shaybanid clans into Turkestan left a vacuum on the steppes north of the Syr-Darya which was rapidly filled by the 'Kazakh' clans. . . From this time onwards the terms 'Kazakh' and 'Uzbek' assume a new significance, the former designating the tribe remaining north of the Syr-Darya and the latter, those which had followed Muhammed Shayband and established themselves south of the river. Both were, however, derived from the same ancestral clans. . . (Hambly, 1969:142)

With these kinds of linguistic and nomenclature difficulties, in addition to the lack of written records, the fortunes of these groups remains an historic problem.

The Turkomans were fierce invaderes, speakers of Oghuz or western Turkish dialects, related to Azeri and Anatolian Turkish,

". . . the Turkomans, the Kara-Kalpaks, and the Kazakhs retained, down to the period of the Russian conquest, their traditional nomadic life as stock-breeders, continuing their ancient quarrels with the inhabitants of the oases who were now as often of Uzbek origin as of Tajik." (ibid.:173)

The Uyghurs are a little known Turkic group who founded several small but elegant civilizations on the Chinese frontier in the Tarim and Turfan basins. They have been Manicheans, Nestorian Christians, and Moslems. To date, little has been published regarding their dance and music. The Uyghurs live scattered among several of the Central Asian Republics and in Sinkiang province in China.

The Tajiks are Iranian language speakers and form the oldest, most continuous ethnic group in Central Asia. The work 'Tajik' has an unknown origin. The only clue I have found to date is the following:

"In reality this represents a recrudescence of Turoman-Persian antipathy in its most violent form. More than anything else, the Qisilbash resented being placed under the command of a Persian, the wazir, Mirza Salman. It was over seventy years since a Persian, or, to use the pejorative term favoured by the Cizilbash, a Tajik, had held such high military command. The fundamental dichotomy is the Safavid state between Turk and Persian was nevertheless as sharp as ever." (Cambridge History of Islam, 1970:412)

In addition to the river valleys and oases of Transoxania, The Tajiks also inhabit the mountain fastnesses of the Pamirs in Tajikistan and Afghanistan. The Persian element in Afghanistan, whether called Tajik, Afghan, Iranian, etc. are the second most numerous group in Afghanistan, and because they were the economic power of the cities, they have been the rulers of state until quite recently when the Pashtun-speakers have been forcing their way into sharing positions of power. Although officially a bilingual state, it was significant that the banks carry on all of their business in Persion, now called Dari in Afghanistan.

Because of the shifting political units, ethnic groups, and historical currents, it is sometimes difficult to keep the names of the different regions clear. For example, the area that is currently Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenia, or parts thereof, has been known as Mawarannahr, Transoxania, Turkestan, plus the names of the aforementioned republics, the emirate of Bukhara, emirate of Khiva, etc. Maps of different historical time periods will contain different geographic terms. All of this historical data is important to discern the many threads in the tapestry of Central Asia performing arts.

MUSIC AND DANCE1

When discussing the music and dance of any Asiatic tradition, it is important to distinguish among several social milieus in which dancing may be seen and heard: 1. nomadic groups2. sedentary rural village – domestic, non-professional3. professional village performers – often itinerant, 4. urban folk – professional and non-professional, 5. urban professional, classical, artists.

Folk songs are of anonymous origin and accompany most phases of life from cradle-to-grave, and in this way, they function intimately in and reflect all of the aspects of folk life style. Whether or not the performers are amateurs or professionals hired for special festive occasions such as circumcisions, weddings, or no-ruz (New Year), for example, the performances are a part of the life cycle. The professional bards (akin, bahkši, etc.) function as both entertainment and as a tie with the past and the larger ethnic unit.

Art and classical music and dance is performed by urban, professional performers, however, and these classical traditions deal with concepts beyond the mundane life cycle. Here dance, music, and poetry reflect the intellectual, religious, learned philosophical, and aesthetic trends and currents of the educated elite in an elegant, sophisticated, and mannered fashion. These traditional forms are, however, not effete, but rather vigorous and exciting in form, content, and performance.

The interest and excitement of the music and dance of Central Asia is the co-existence and interplay between all of these artistic and cultural traditions and the societies they reflect. Because of the two opposing life styles represented here – sedentary and pastoral nomad – we can divide the music and dance of the sedentary Tajiks and Uzbeks on the one hand from the traditionally pastoral Kazakhs and Kirgiz on the other, with the Turkomans serving as a transitional group.

Aside from a body of domestic folk music, the Kazakhs and Kirgiz have developed a very broad and rich heroic, epic tradition in which bards called akin accompany themselves on string instruments. This is a three-stringed, fretless, plucked lute called a komuz in Kirgizia, and a two-stringed lute with tried-on frets called dombra in Kazakhistan.

This is, then, a kind of professional music, since the bards are often professionals. They are noted for their ability to embellish texts, vocal styling, and instrumental playing. The music serves to enhance the text, and is secondary in importance and not highly elaborated. In Kazakhistan and Kirgizia, the poetry is in folk style (non-literary) and metre and is traditionally orally transmitted history. Aside from the massive national histories of each of these groups, such as the Kirgiz Manas, there are many shorter epics of heroes and battles, brave maidens, and of love stories. The Kor-oğli or Gur-oğli cycle is common to all the groups and extends all the way into Antolian Turkey, Azerbaijan, and other Turkic-speaking areas. The Tajik literature, Ferdowsi's Shahname, the King's Books, finished around the year 1,000 BCE. It holds a place in Iranian and Tajik literature similar to Shakespeare in the English-speaking world.

Only in recent times has the epic poetry of the Kazakhs and Kirgiz been set down in writing.

The Turkomans also have an epic tradition, but because of their longer association with the Uzbeks and Tajiks, much of their professional poetry is composed by use of the aruz system of vowel length utilized by classical Persian poets, and literary poetic forms such as the ğazal are composed by Turkoman poets and bards. Their novelistic epics are termed destan (Persian for "story") and are shorter and not connected like the Kirgiz Manas cycle. Among the Tajiks and Uzbeks literary epic love stories that are current throughout the entire Middle East such as Leila and Majnun, Farhad and Shirin, etc. are still recounted.

The Turkoman also show their cultural association with the Uzbek and Tajik tradition by the use of the dotar (dutar), a plucked lute for musical accompaniment. It should be mentioned in passing that some instruments are associated with professional musicians while others are considered only suitable to informal and domestic use.

All of the groups in Central Asia use a bowed fiddle (played in the manner of a cello, but balanced on the knee and much smaller). These instruments have several forms, but are called variously rabob, ğičak, kiak, kobiz, etc. and they are related to or similar to the Iranian kemanče and Indian sarinda. These bowed fiddles were apparently once more popular with bards than now.

The plucked instruments have increasingly taken on a status of a virtuoso, solo instrument and their players have developed a wide body of musical selections that might be likened to etudes. Non-professional folk musicians also play these instruments for accompanying songs and dances as well.

The folk songs of the Turkomans and Kirgiz are very narrow in range, rarely exceeding a fifth or sixth, while Kazakh songs have a wider range, often exceeding the octave. The folk music of these three groups does not contain the more elaborate range and embellishment of the Tajiks and Uzbeks. Art music in the sense of the Tajik-Uzbek classical traditions does not exist, although instrumental music since the time of the Soviet regime shows a trend in the direction.

The professional musicians, as one might expect, utilize a wider range of tones. In addition, the professional Turkoman singer employs a wide range of vocal sounds and sound effects to embellish his music, and once heard, are not forgotten. This vocal style lends a special piquancy and a charm to Tukoman music. (For those who attended the concerts of the Mahalli Dancers of Iran, one of the most outstanding moments was the performance of a trio of Turkoman musicians employing this vocal styling.)

The jew's harp is an instrument played throughout Central Asia, almost exclusively by women and/or children and called variously čang, san kobiz, gopis, etc.

For Turkmenia, Kirgizia, and Kazakhistan, no mention of percussion instruments for musical performances is mentioned, but I believe that frame drums may have been used for shamanistic ceremonies.

All of these areas used a military orchestra of winds and percussion. These double-reed instruments are such as sarnai (surna), karnsi, etc., and accompanied by large and small kettledrums, daulpaz, čindaul, nagora, etc. were a feature of nomadic and urban court life.

"The Tajik military was band was an indispensable accessory of court life and was housed in a special open pavilion, built over the gates of the citadel, the residence of the feudal ruler. In telling the hours of the day, the orchestra played specific works. . . In addition to these basic functions, the military orchestra also took part in campaigns, parades, and military exercises of the sarbas, the Khan's soldiers. . ." (Delisev, 1975:222)

The director of this orchestra was known as mehter or master, and this orchestra is called mehter in Turkey today. The instruments and the functions these orchestras fulfilled are very ancient, and are originally Near Eastern.

Little investigation has been undertaken in regards to the dances of the Kirgiz, Kazakhs, and Turkomans, and indeed, it has been often stated (by Russians) that choreography is a young art among these peoples.2 Certainly, most of the current repertoire of the "national" companies is new, and very Soviet in concept execution. Percussion instruments, as has been mentioned, are few and recordings and musical notations of dance tunes other than newly composed, do not seem to exist. Soviet researchers are of the opinion that this is because of their nomadic lifestyle, which they claim was not conducive to dancing. I have seen Turkoman men dancing in Gonbad-e Qābus. The men's dance, djigit, is performed both by soloists and groups, and depicts aspects and movements of horesback riding. Other men's dances are performed as well. They are simple in form and ponderous in movement, danced with no musical accompaniment other than guttural sounds made by the dancers – somewhere between a grunt and a belch – and the stamping of the feet. The dancing is quite awe-inspiring in its strength. The power of the dance makes up for its almost total lack of grace.

I have never seen women's dancing, except for the dance piala (bowl), performed by a soloist from Bahor, the Uzbek State Company. This dance is also described in Tkachenko (see bibliography). This does not mean that female dancing does not exist, but it does mean that male researchers are hampered in Islamic societies when enquiring about female dancing.

The Uzbeks and Tajiks share a common urban and rural musical dance tradition. This is because of the Uzbek conquest of Transoxiana (the area north of the Oxus or Amu-Darya River which includes most of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan). The Uzbeks rapidly adopted the Tajik lifestyle, and in many areas, the two groups became bilingual.

Folk styles have some regional variation; especially the mountain Tajiks of the Pamirs and Badakhshan in neighboring Afghanistan have maintained a distinctive, ancient tradition that is much less elaborate than that of the river valleys and the urban centers.

Unlike the Turkoman, Kirgiz, and Kazakh traditions, the historical data for Tajik and Uzbek urban music is clearly documented. The Aitrim frieze in Termes, Tajikistan, dates back to the first centures before Christ and clearly shows the instruments played. During the medieval period several treatises and biographies of musicians were written, the most important of which are those by Al-Fārābī and Abu-Ali Sina (Avicenna). (These have been translated into French – see D'Erlanger in the bibliography.) In Korazmia, a musical notation system, was developed and when compared with the Šaš maqam (six modes), as published by the Tajik Academy of Sciences, the playing and performing of the vocal and instrumental suites has little changed in four centuries.

All of this investigation reveals an elaborate and brilliant dance and music tradition. This dance and music tradition is, in its own way, as highly developed as the classical traditions of the West.

Folk music of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan also demonstrates more elaboration than the Turkoman, Kirgiz, and Kazakh traditions by having wider ambience to tonal range, more scales, more musical instruments, and considerable elements from the classical tradition.

Basically, the poetry of folk music is folk, which is to say, the ruba'i or quatrain (four lines). This style of the quatrain is avoided by professional poets because of its folk (that is, vulgar) associations and origins; it is in a word, doggerel. This is incidentally why Omare Khayyam is not considered a major poet in Iranian-Tajik traditions. (Ruba'iyyat is the plural of rub-a, and is a collection of unrelated quatrains.)

Among the many charming folk songs of the Tajiks and Uzbeks is a special type called lapar. Lapar are exchanges of wit between two contestants, often a man and a woman. Verses are made up on the spot and sometimes the onlookers clap and repeat some of the lines made up by the principals. Dance movements also accompany these contests of wit, and they are a source of great entertainment to the people.

Folk plays also feature folk poetry, music, and movement in miming that approach dancing.

Folk poetry is based on the amount of syllables to a line, whereas, literary poetry which is used for classical vocal music is based on the strictly formal system of metrics of vowel length known as aruz. This type of poetry firmly links Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to the mainstream of Middle Eastern culture. Classical music is highly elaborate and suites of vocal and instrumental music played by large instrumental ensembles is a long tradition of this area.

After the establishment of the Saffavid dynasty in the 16th century in Iran, the Shi'i sect of Islam was elevated to the status of official state religion. At this point the Sunni Moslems (Orthodox) of Central Asia ceased almost all cultural exchange with the Middle East, with which they had formed an integral cultural and historical unit. This split between Shi'i and Sunni Islam is somewhat analogous to the Catholic-Protestant schism of about the same time in Europe. Many scholars felt that this resulted in a long period of cultural decline and stagnation, characterized by a "freezing" or "fossilization" of musical style and performance. Thus, improvisation on the scale of elaboration and artistic level of that performed in Iran, and its paramount importance in Persian classical music does not exist in Uzbek and Tajik music with its more fixed performance.

Nevertheless, the scales and modes and musical terminology used in Uzbek and Tajik classical music demonstrates the common aesthetic bases and relationships and origins of these musical forms.

Also, the musical instruments, sometimes called by different names (čang, santur, kemanče, ğičak, etc.) were developed jointly in Iran and Central Asia.

The technical details of music are beyond the scope of this presentation, but the interested reader may find detailed information in works cited in the bibliography.

Music for dancing is extensive in Tajikistan.3 It is accompanied in several ways: 1. by solo daireh (doire), a kind of frame drum, played in virtuoso manner as a solo instrument. (Professional daireh players learn a complex series of rhythms known as usul. Several examples may be found in Karimova: 1975 and D'Erlanger: 1930-59). 2. Solo instruments such as dotar with the kaireh or tavlak (goblet drum similar to the Iranian dombak). 3. orchestras. 4. group or solo singing with or without instrumental accompaniment and handclapping.

The dancing is by soloists or group dancing as an extension of the solo dances. Line and circle dances where the dancers hold hands are not performed in this area, although circle dances with each dancer functioning by his or herself are common. Solo dancing is highly virtuosic, especially that of women, where acrobatic elements are featured. The finest dancers will improvise with thedaireh player. The classical dance style of this area, however, unlike the almost totally improvised Iranian solo dancing, has been elaborated by its performers into a series of very complex, stylized movements which convey, 1. work movements of domestic and field chores, or 2. poetic concepts and a terminology has been developed to designate the movements and series of movements.

As in much of the Middle East, the social status of the professional dancers, young female and male, is beyond the pale of society. Whereas in Iran with the end of the Qajar dynasty, this caste-like group largely faded away, in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, the Soviet authorities with an essentially Western moralistic outlook, have encouraged and subsidized the more quality aspects of this art form, and suppressed the considerable erotic content of this dancing. In Afghanistan, young males as professional dancers plied their trade until quite recently. (A vivid description of this is Jams Michener's "Caravans," a portrait of life as it was in Afghanistan around 1958 to 1963.)

Among the finest exponents of this art form are the soloists, corps, and musicians of the Bahor Dance Company of Uzbekistan, under the expert direction of Mugharam Turgenbaeva, who has developed a rich repertoire of solo and group dances of all of the areas of Central Asia.

Rural dances of women portray, for the most part, domestic and field work movements, many mimetic dances of animals and old people, etc., often highly comic, and dances with swords.

Unlike Europe and adjacent areas of the Middle East such as Turkey, Lebanon and Syria, step patterns and footwork are relative unimportant. The main concentration of the dancing is in the hands, fingers, head, face, and torso. The movements and isolation movements of these parts of the body is the main focus of the dance. The Pathan (Pashtoon) men for example, move in a circle using a simple step in the dance Aten, but the salient feature of the dance is the gyrating of the heads with their long hair whipping wildly about until the dancers, with ever increasing tempo, reach an almost ecstatic state.

In Uzbek and Tajik classical dancing, the movements of the hands, arms, upper torso, facial features, and head, give the watcher the feeling that these performers have no bones, so plastic and supple are the gestures.

Central Asia is one of the last researched areas of the world in music and particularly dance. Theirs is a rich, multifaceted dance tradition, and it is hoped that this brief survey will encourage dance researchers to explore this untapped area of choreographic wealth.

NOTES

- For the discussion of music, I relied very heavily on Beliaev's work on Central Asian Music, with Mark Slobin's excellent commentary and editing. Because much of the available research work in this area has been done by Soviet scholars, it should be mentioned that they work in a particular theoretical framework. For example, they have an evolutionary social scheme in which groups of seemingly "primitive" social and economic development have simpler forms of music and dance. This is why they state that choreography is a young art in Kazakhistan (heard in a film soundtrack). I feel that this is a simplistic theoretical approach, however, for in Iran tribal groupings such as the Qashqa'i have better developed, more elaborate dancing than the sedentary groups in the same area because of other factors such as religion. Also, Soviet musicologists do not notate in microtones, an integral feature of Central Asian and Caucasian music, because Soviet music should be played on the tempered scale. This means that all musical notations in Soviet musical publications must be used with care.

- Again, not enough research has been done in this area. Also, one of the factors in the development and elaboration of dance forms and movements, is the degree to which the members of any society find dancing a desirable form to develop and practice. This factor is too often ignored by researchers.

- Many recordings of Uzbek and Tajik music, classical and folk, are available on Melodiya records. They are of excellent quality and use microtones.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

General History

- Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1, The Central Islamic Lands. Editors: Holt, P.M., Lambton, Ann K.S, and Lewis, Bernard – Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- Grousset, Rene. Empire of the Steppes Translated by Naomi Walford, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Rutgers University Press, 1970.

- Hambly, Gavin, editor, Central Asia. New York, Delacorte Press, 1969.

Dance

- Karlimova, R. Ferghanskii Tanets (Dances of Ferghans, in Russian). Tashkent, Guliamn, 1973. Highly illustrated.

- Karlimova, R. Khorezmskii Tanets (Dances of Khorazmia, in Russian). Tashkent, Guliamn, 1975. Highly illustrated. Similar to Ferghanskii Tanets but contains more information on the resource people.

- Nurjanov, N. "Razvlecheniia i narodny teatr tadjikov Karategina i Darvaza." In Isskustvo Tajkikogo Narodna (in Russian), vol. 3. Dushanbe, Donish, 1965:113-152. Illustrated article on folk dance and theatre in the Tajik districts of Karategina and Darvaza. Contains line drawings of a women's dance.

- Thachenko, T. Narodny Tanets (Folk Dances, in Russian). Moscow, Iskusatvo, 1954. A brief survey and historical overview of the dances of the major ethnic groups of the Soviet Union. Examples of dances, a compendium of the basic movements of each dance style, with clear line drawings. A basic title, portions of which have been translated into English.

Music of Central Asia

- Belisev, Viktor. Central Asian Music. Edited and annotated by Mark Slobin, translated by Mark and Greta Slobin. Middletown, Connecticut, Wesleyan University Press, 1975. This is a prime source whichwas used for the more technical discussions of music. The editor, Dr. Slobin, is probably the most knowledgeable scholar in the United States in the music of Central Asia.

- Dansker, O. "Muzykal'naia kul'tura tajikov Karategina i Darvaza." In Isskustvo tajikogo narodna, vol. 3. Dushanbe, Donish, 1965. There are several musical examples of the music of the Tajiks of Karategina and Darvaza, and on p. 252, a photograph of a man playing the tar, a musical instrument widely used in Persian classical music and not mentioned in Belisev or in the listings of the Atlas.

- Slobin, Mark. Kirgiz Instrumental Music. New York, New York. Asian Music Publications, 1969.

- Tajikova, G. "K voprusu o sootnoshenii metriki stikhoslozheniia a metroritmikoi napeva v tajikskikh pesniakh." In Akhbarot. Tajik Academy of Sciented, no. 2. 1968:84-94. A discussion of folk poetry and metre and literary forms.

- Vertkov, V et al. Atlas muzykal'nykh instrumentov parodov SSR. Moscow, Muzyka, 1963. A basic work for any study of instrumental music of all areas of the Soviet Union. It contains clear photographs of each instrument with a description (in Russian) of all of the instruments of each ethnographic unit. I did see a photograph of a Tajik orchestra with three tar players, buyt the instrument was not mentioned in the catalogue section. The musical notation must be used with card because the microtones are not notated nor mentioned.

Related Works on Middle Eastern Music

- Barkechii, Nehdi. La Musique Traditionnelle de L'Iran. (In French and Persian.) Tehran, Ministry of Fine Arts, 1963. A very important compendium of Iranian musical scales and modes (redif) and discussion of musical theory. May be compared to Šaš-maqam.

- D'Erlanger, Baron Rudolphe. La Musique Arabe (in French), 6 vols. Paris, Library orinetaliste Paul Guethner, 1930-59. Basic study of historical aspects of Middle Eastern music, including translations of the musical histories and treatises of Al-Fārābī and Abu-Ali Sina (Avicenna). Also includes studies of usul, rhythmic combinations.

- Farhat, Hormoz. Dastgah Concept in Persian Music. Ann Arbor, University Microfilms, 1965. An invaluable, highly technical discussion of scales, modes, microtones, and other aspects of the structure and performance of Iranian music.

- Zonis, Ella. Classical Persian Music, an Introduction. Cambridge Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1973. Good, but technical understanding of the basic structures and theories of Persian classical music. Somewhat easier to understand than Farhat.

DOCUMENTS

- Anthony Shay, an article.

- Asia, a region.

Used with permission of the author.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, June 1978, under the title "Music and Dance of Central Asia"

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.