|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

History of By Don Buskirk

YouTubes illustrating or amplifying the topic discussed are

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia |

Periodicals | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

1st Phase: 1880's – 1930's; From the (intellectual) Top

What are 'we' going to do about 'them' in our midst? Making 'them' more like 'us'?

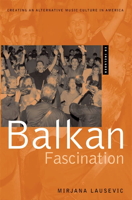

I am indebted to Mirjana Laušević, whose book Balkan Fascination [Oxford University Press, 2007] is the foundation of the historical references in this article. I have borrowed extensively from her writings. Excerpts from Laušević's book are in italics. However, it should be assumed that opinions expressed regarding developments outlined here are not those of Laušević, but those arising from my personal experience.

I am indebted to Mirjana Laušević, whose book Balkan Fascination [Oxford University Press, 2007] is the foundation of the historical references in this article. I have borrowed extensively from her writings. Excerpts from Laušević's book are in italics. However, it should be assumed that opinions expressed regarding developments outlined here are not those of Laušević, but those arising from my personal experience.

Below I describe the first of three rather distinct phases in the development of what we now call recreational or international folk dancing. In each phase 'we,' the settled Americans driving the phase, had a different idea of who 'they,' the 'folk' were, and therefore why 'we' wanted to dance 'their' dances. For let's be clear – folk dancing is not, among recreational folk dancers anyway, dancing BY the 'folk,' it's US dancing our IDEA of the 'folk.' It's one culture selectively imagining another for its own purposes. What those purposes are helps define what we imagine the 'folk' to be, and how we conceptualize and dance 'their' dances.

Immigration in the United States

The ethnic composition of those immigrating to the United States during the first 75 years after Independence [setting aside for the moment the nearly-exterminated Native Americans, the forcibly-imported, de-humanized Afro-Americans, and the marginalized Latin-Americans], consisted mostly of North and West European stock, including Germans, Irish, French, and Scandinavians – the 'first wave' of immigrants. Though they might not speak English, they were still mostly from related cultural backgrounds, as well-educated as the English, Scottish, and Dutch immigrants considered 'real' Americans, and relatively easily assimilated into the American experiment.

The ethnic composition of those immigrating to the United States during the first 75 years after Independence [setting aside for the moment the nearly-exterminated Native Americans, the forcibly-imported, de-humanized Afro-Americans, and the marginalized Latin-Americans], consisted mostly of North and West European stock, including Germans, Irish, French, and Scandinavians – the 'first wave' of immigrants. Though they might not speak English, they were still mostly from related cultural backgrounds, as well-educated as the English, Scottish, and Dutch immigrants considered 'real' Americans, and relatively easily assimilated into the American experiment.

After the Civil War, industrialization became the driving force of the economy – raw capitalism [as in Britain, France, and Germany] with few constraints on greed. A flood of immigrants from beyond Anglo-Saxon Europe arrived to feed the machines – 25 million between 1880 and 1930. The bulk of this 'second wave' consisted of southern and eastern Europeans – Italians, Greeks, Poles, Yugoslavs, Bulgarians, Russians, Hungarians, Romanians, Jews, and Roma from all those countries. They usually didn't speak English, were often illiterate, and were thus easily exploited [children as well as adults] by factory owners. They congregated in unsanitary city slums, worked unspeakably long, dangerous hours for low pay. They were often too poor or exhausted for 'socializing, dining, and dancing together.' The first phase in the development of folk dancing in the United States was concerned with what to do about this 'second wave' flood of new immigrants.

American attitudes toward the new immigrants were far from uniform. Milton Gordon, in Assimilation in American Life [Oxford University Press, 1964], writes of three main axes around which the 'philosophies' of immigration have grouped themselves (and still do!):

1. 'Anglo conformity.' "Central to the Anglo conformity theory was the demand for a 'complete renunciation of the immigrant's ancestral culture in favor of the behavior and values of the Anglo-Saxon core group."

2. 'The melting pot.' "A vision of America as a melting pot supported "a biological merger of the Anglo-Saxon people with other immigrant groups and a blending of their respective culture into a new indigenous American type."

3. 'Cultural pluralism.' "The preservation of the communal life and significant portions of the culture of the later immigrant groups within the context of American citizenship and political and economic integration into American society."

By the 1880's, what to do about immigrants' sufferings had become a concern among well-meaning 'established' Americans. Liberal middle-class Americans had already joined their European brethren in denouncing the materialism and spiritual sterility of modern society, and believed social reform was necessary. The writings and ideas of Leo Tolstoy, Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, and William Morris, as well as Americans Stanley Hall, Felix Adler, and John Dewey coalesced into the notion that, as Carlyle put it, "We are all bound together, for mutual good or else for mutual misery, as living nerves of the same body. No highest man can disunite himself from any lowest." The idea of progress was framed by the idea of a universal humanity which, since all people were connected, the betterment of one led to the betterment of others. Thus, the progress of humanity was not progress in terms of modernization and economic efficiency, but through democracy, 'cultural pluralism,' equality, mutual appreciation; it would be achieved by partaking of one another's lives and cultures, learning through experience and example, finding artistic means of self-expression.

The Settlement Movement

Again quoting Milton Gordon's Assimilation in American Life, "The first manifestation of an ideological counterattack against draconic Americanization came not from beleagered newcomers, who were, after all, more concerned with survival than with theories of adjustment, but from those idealistic members of the middle class who...'settled' in the slums to 'learn to sup sorrow with the poor.'"

Again quoting Milton Gordon's Assimilation in American Life, "The first manifestation of an ideological counterattack against draconic Americanization came not from beleagered newcomers, who were, after all, more concerned with survival than with theories of adjustment, but from those idealistic members of the middle class who...'settled' in the slums to 'learn to sup sorrow with the poor.'"

The majority of established, comfortable Americans were unaware of the living conditions of the American poor and recent immigrants. Some pioneers of the settlement movement literally stumbled across the poor, and this initial contact motivated some of them to establish a 'settlement house.' Settlement houses, built and inhabited by comfortably well-off 'mainstream' Americans were located in the midst of poor neighborhoods in the hope of educating and Americanizing their inhabitants. Calling the poor and immigrants 'neighbors' emphasized not only physical proximity, but intimacy and interdependence. The idea behind settling among 'neighbors' was that this immersion would enable the 'residents' to learn more about the needs and deficiencies of the 'neighborhood' settled. At some time the 'neighbors' would become good American citizens by modeling themselves after the highly educated, upper-middle class 'residents.' The first settlement house in the United States was founded in New York in 1886, followed by Chicago, 1889. By 1897, there were 74 nationwide; by 1911, 413.

The bulk of settlement work was realized through clubs, classes and services. Supervised by the head of the settlement, a number of residents, usually college graduates from well-off families, interested in social work, lived in the settlements and provided and organized various kinds of services and activities for "the neighbors". These ranged from distributing milk, arranging visiting-nurse services, giving hygiene and cooking instruction, providing childcare and playground space, to teaching English and citizenship classes, founding music schools, and organizing folk dancing. Why Folk Dancing?

American settlement workers fought the perceived evils of urban life – saloons, dance halls, and prostitution – which reflected a lack of moral laws and traditional values of order and respect. The American cultural elite, to which most leaders of the movement belonged, were generally opposed to commercial forms of entertainment for youth; American and immigrant alike. The dance hall was seen as an embodiment of many ills in contemporary American society. Youth gathered, unsupervised by adults, to dance popular couple dances to racy 'syncopated' music, free to change partners from one dance to the next; creating social promiscuity. What's more, many working-class dance halls were attached to saloons, with liquor and prostitution as part of the scene.

Jane Addams, a leader of the settlement movement, wrote in 1909, "Perhaps never before have the pleasures of the young and mature become so definitely separated as in the modern city...the public dance halls filled with frivolous and irresponsible young people in a feverish search for pleasure, are but a sorry substitute for the old dances on the village green in which all of the people of the village participated." The promotion of folk dancing thus needs to be seen partly as a substitute for the scourge of dance halls and associated activities.

This longing for a pre-urban, pre-industrial lifestyle, considered an antidote to the ills of the modern city, was among the motivating factors in the organization of 'international' festivals, pageants, and folk dance classes. The young 'residents,' while working to execute the ideals of the cultural elite, "found in these exotic celebrations the brighter side of the urban 'reality' they sought. Here were genuine manifestations of the European folkways they had read about in college, nostalgic survivals of 'simpler' pre-industrial cultures" wrote Addams in 1910.

To quote Laušević: "The immigrants who were the focus of American settlement work were positioned ambivalently. They were seen, at once, as an embodiment of pastoral, pre-industrial culture and as the main spinners of the industrial wheels, their poverty symbolizing both the failure of modernism and the destruction of traditional values. The immigrants were seen as possessing the "tradition" and "cultural wealth" of the Old World (folklore, close-knit community, and traditional values), a wealth that America needed. But urban industrial America was seen to be destroying the best of the immigrants' possessions while at the same time longing to have those possessions herself."

Folk Dance as practiced in the settlement movement

Like the settlement movement itself, folk dance as practiced in settlement houses was a top-down affair – the dances filtered pre-approved as appropriate for the purposes intended. Among the purposes intended, learning in-depth information about other cultures was not high on the list. What was deemed important was that dancers of many ethnicities left their ghettos and attempted to communicate across ethnic boundaries – that they mingled and learned to get along as a step toward integrating into their new homeland. Cultural pluralism meant that each was allowed to hold on to and display one's heritage, while recognizing he/she was part of a larger picture – the panorama of the new, multi-ethnic democracy.

Like the settlement movement itself, folk dance as practiced in settlement houses was a top-down affair – the dances filtered pre-approved as appropriate for the purposes intended. Among the purposes intended, learning in-depth information about other cultures was not high on the list. What was deemed important was that dancers of many ethnicities left their ghettos and attempted to communicate across ethnic boundaries – that they mingled and learned to get along as a step toward integrating into their new homeland. Cultural pluralism meant that each was allowed to hold on to and display one's heritage, while recognizing he/she was part of a larger picture – the panorama of the new, multi-ethnic democracy.

Dances were not traditional dance patterns from the 'village' taught by natives, they were symbolic representations of a country's 'essence.' To accompany folk dances, fidelity to the musical practices of a source culture was seldom taken into account. Little attempt was made to employ 'folk' instruments. Sound recordings had only recently been invented, and nothing 'ethnic' had been recorded. Dances were accompanied by a piano, violin, or a brass band – whatever local musicians were available. Ethnically appropriate sheet music was almost impossible to come by, so classical music of a similar tempo or phrasing structure was substituted.

When the settlement houses sponsored a festival or pageant, as stated in the Report of the Henry Street Settlement, 1893-1914 ... "To the music of the festivals we have given great consideration. The ritual chants and synagogal melodies have been gathered after careful research. For the dances and other musical settings we have incorporated classical compositions that seem to suggest the idea most fittingly. Symbolism has been the keynote of the color schemes in costume and stage-setting, and it is with utmost regard for the symbol or idea that the dances have been developed. On every hand we attempt to suggest rather than represent, to interpret rather than describe." This is a good illustration of the treatment of folk material in pageants and festivals, where neither the "authenticity" nor the "stylistic purity" of the repertoire was a concern.

The Physical Education and Recreation Movements

The intellectual environment that produced the settlement movement in the United States also had a great influence on the development of physical education and recreation movements. While immigrants were increasingly doing the nation's manual labor, native-born Americans were leaving farms and migrating to cities to fill newly-created factory and office positions. Dance halls and saloons affected them as well, so the solutions prescribed for the ills of immigrants were also applied to the native-born.

The intellectual environment that produced the settlement movement in the United States also had a great influence on the development of physical education and recreation movements. While immigrants were increasingly doing the nation's manual labor, native-born Americans were leaving farms and migrating to cities to fill newly-created factory and office positions. Dance halls and saloons affected them as well, so the solutions prescribed for the ills of immigrants were also applied to the native-born.

"The Provost Marshal General reported in 1918 that about 30 to 53 percent of men called up in the Selective Service Draft were rejected...The reported number represent only a statistical confirmation of a concern shared widely by physicians, anthropometrists, and physical educators that American Urban Youth (male and female) were physically underdeveloped and deformed due to insufficient physical activity and systematic exercise. Urban living conditions were seen as the main cause of this sloth. Working youths spent their days sitting in offices or doing repetitive movements in factories. Even children, cramped in crowded neighborhoods without space for play, were physically inactive. The dirt and traffic on city streets kept children from playing and socializing on the only available outdoor space."

Enter the Physical Education Movement. Before 1900, as a part of physical education in school curricula and various recreational organizations, folk dancing was already being taught in Germany, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, England, and other European countries. These programs were designed to foster patriotism by teaching only the dances of their national ethnicity. Those ethnic groups had similar programs among their immigrants in the United States, but for the United States, patriotism would be fostered by teaching dances of all ethnicities – showcasing democracy by highlighting inclusiveness.

Although gymnastics and other exercise programs were promoted in schools, "folk dancing took priority over other forms for a number of practical reasons. The cost of establishing a folk dance program was extremely low compared to building properly furnished gymnasia. Folk dance required very little room and could be done in existing spaces such as school roofs or classrooms, playgrounds, church basements, community rooms, parks, even streets. The activity was suitable for all ages and both sexes, whether they were dancing together or independently. A single teacher could simultaneously instruct large numbers of students. The time allotted for physical education was used to its maximum – there was no waiting since everybody danced together. It was due, in part, to these practical advantages that folk dancing became so popular in recreational and physical education."

"Folk dance programs were not established for the purpose of studying folk dances themselves. Rather, these programs were the vehicles for achieving a specific set of goals, such as physical fitness, nationalism, patriotism, social cohesion, character building, and racial superiority."

However, there was a hitch. Hardly anyone teaching phys ed had seen folk dances in 'the village.' It wasn't taught in teaching academies, it hadn't been experienced in middle-class school playgrounds. How were instructors supposed to acquire this knowledge?

"It is difficult to determine when and where the first folk dance classes were offered in school and college physical education programs. Folk dancing was introduced independently at several schools and colleges around the country...as early as 1884 and much more frequently in the first years of the 20th century. The generic term 'dancing' was often the only term used in course descriptions before the turn of the century...Even if the the dance programs were labeled folk, we cannot say with certainty what the label meant at the time, or what material was presented. For example, Mary Wood Hinman defines her classes as 'a combination of ball-room and folk dancing.' The titles of dance instructors are not much more helpful, as they varied from one institution to another. [One year after] dancing was introduced into the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics [in (1898-99),] Melvin Ballou Gilbert was appointed as 'instructor in aesthetic dancing.' Two of the most prominent folk dance teachers, Mary Wood Hinman and Elizabeth Burchenal, studied dance with Melvin Ballou Gilbert, although there is no evidence that he gave instruction in folk dancing.

The Pioneers: Hinman, Gulick, Burchenal, Chalif – and Henry Ford?

"Mary Wood Hinman was one of the first professional folk dance teachers in the United States – an inspiration for many women who were trying to make a living in dance...beginning in 1898...she offered classes at Hull House...and taught at other settlements around Chicago, providing a direct link between the settlement house and physical education movements. She also taught in John Dewey's schools...and later provided summer school instruction at Columbia University in New York. In 1904 she opened the Hinman School of Gymnastic and Folk Dancing, and Hinman Normal School. She achieved considerable national influence both through her own instruction and that of her students.

Perhaps Hinman's most far-reaching influence came through her numerous publications of folk dance instruction and musical accompaniment that were used by teachers across the country...In some cases, along with the usual piano arrangement of the music and sketchy step description, Hinman left us brief and somewhat enigmatic references to the sources of her material...Hinman studied various kinds of dance with Chicago dance teachers, dance callers, and perhaps even people in Chicago's ethnic communities [emphasis mine]. She also 'visited Sweden to study folk dances and games at the college of Naas, and traveled in northern Sweden learning dances. At other times she journeyed to Denmark, Russia, and Ireland, in each case studying and collecting traditional dance material firsthand.'"

"Luther Halsey Gulick, one of the strongest advocates of the folk dance movement, received his degree from the YMCA School in Springfield, Massachusetts, but I have seen no evidence of Gulick receiving folk dance instruction there." He later became director of training for New York Public Schools, and helped found the boys-only Public School Athletic League (PSAL) in 1903. Though folk dancing was not on his curriculum, he admired Elizabeth Burchenal's work at the Teachers College New York, and recruited her in 1905 to form the Girls' Branch of the PSAL – the Girls' Athletic League (GAL). She introduced folk dancing as its main activity.

"The beginning of the folk dance movement is sometimes taken to be 1905, the date when Elizabeth Burchenal established folk dancing in public schools in New York."

"... a brief description of Burchenal teaching the Hungarian Czardas to the group of forty girls at the East Side Public School in New York (fig. 4.4) is a valuable contribution to our understanding of her method of instruction: 'At the close of the program Miss Burchenal inquired if there were any Hungarian girls present who knew the Czardas. The hands of two went up. In a twinkling she had seized the bigger girl by the waist and was whirling her down the room. Immediately the children scrambled for partners and with eyes on the Inspector began to imitate her steps. Falteringly at first, and then more surely and finally with complete confidence, couple after couple made the movement their own until nearly the whole roomful was successfully tripping the intricate steps of the Hungarian national dance.'"

"The long list of Burchenal's folk dance publications includes several hundred dances. However, Burchenal's most significant achievement was the institutionalization of folk dancing in schools across the county."

I have a 1913 edition of Burchenal's Dances of the People. It lists "28 folk dances of the United States, Ireland, England, Scotland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Germany, and Switzerland, with the [sheet] music, directions for performance, and numerous illustrations [photographs]." I could find YouTubes for several:

- Strip the Willow – Scotland. Burchenal lists the dance as English, but nowadays it's mostly Scots who dance it.

- Rinnce Fada (Kerry Dance) Ireland

- Fairy Reel (6-hand Reel) Ireland

- Tantoli – Sweden

- Trekarlspolska – Three Men's Polska – Sweden

- Bleking – Sweden

- Gustaf's Skoal – Sweden

- Feiar – Norway

- Reinlandar – Norway

- The Crested Hen – Denmark

- Syvspring – Seven Jumps – Denmark (Michael Herman's Orchestra)

- Come Let Us Be Joyful – Germany

- Besentanz – Broom Dance – Germany. There are MANY different kinds of broom dances from many countries. This is closest I could find to the singing game described by Burchenal.

Where did she learn all those dances? "... in parts of Europe, folk dancing was already established in school curricula and seminars, and workshops and summer schools of folk dance were available to those interested in learning the national folk dances of a particular country. Elizabeth Burchenal, Mary Wood Hinman, and many other physical education teachers attended such schools of folk dance, including those organized by Cecil Sharp in England."

"The trips were generally focused on "approved" sources of material, that is, those provided by urban intellectuals, national folk societies, and "credible" educated dance instructors. While it might have been much simpler to learn folk dances from immigrants in the United States, such an approach required a mental leap most educators were not ready to make [emphasis mine-DB]. Besides, immigrants were typically only capable of teaching dances from their native locality. I have not encountered a single account from this period of an immigrant being invited to teach a folk dance from his/her tradition to school children. On the contrary there were concerns expressed about learning dances from uneducated immigrants. This attests to a feeling that it was foreign lands themselves, more than the people, who were the cradles of tradition. Material gathered abroad was treated as the most authentic, though it might have been much more stylized than a dance enjoyed in an immigrant community at home." Immigrants already in the United States were not considered 'pure' enough to be trusted as the 'embodiment of pastoral, pre-industrial culture.' Information about peasant dances did not flow from 'their' peasant-to-'our' scholar, it flowed from scholar-to-scholar.

Such an 'approved' source of 'folk' dances in, say, Serbia in the early 1900's, would likely be the court and urban dancing masters. Dick Crum, in a 1954 article in Viltis magazine, explains, "A long struggle to liberate itself from the Turks had built up within the Serbs an intense nationalism which appeared in their literature, music, and other facets of their culture. The way in which this national pride evidenced itself in the city dances is particularly interesting. City dancing masters began looking toward the folk dances for inspiration, and started composing ballroom dances in the native idiom. Along with the French quadrilles and other dances in vogue at urban balls, there began to appear 'kolo' dances, done in circles and lines, patterned after the kolos done in the villages. In many cases the dancing masters borrowed melodies and steps directly from the village dances, but these were usually a bit too brusque or crude, so they composed melodies and manufactured steps and figures, in an attempt to combine the folk element with the courtly style that was fashionable at the time."

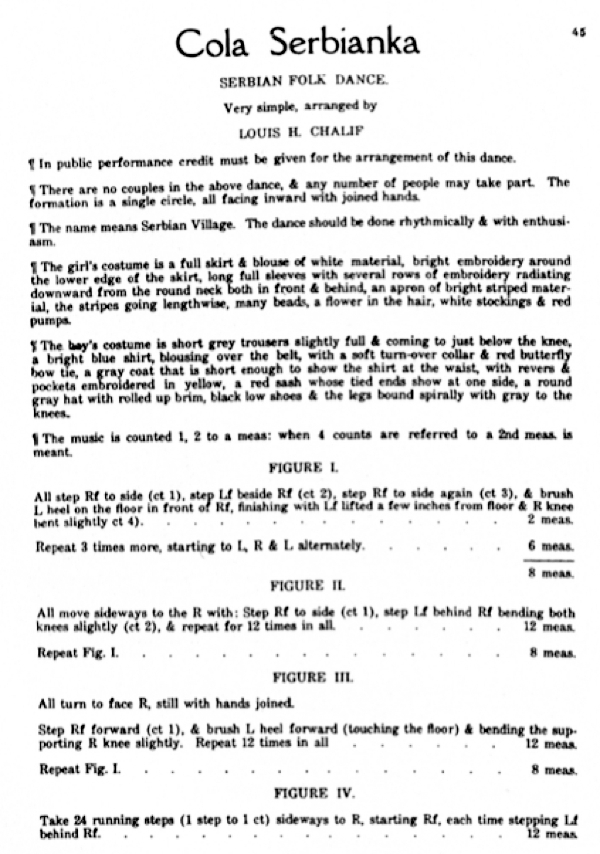

"In 1905, the very same year Burchenal established folk dancing in public schools, Louis Chalif taught a class at the American Society of Professors of Dancing. Chalif (1876-1948) was a renowned Russian ballet dancer who, in 1904, danced at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. On that occasion Luther Gulick...invited Chalif to stay in New York and start a normal school of dance...Gulick himself organized the folk dance class for physical education teachers that Chalif taught in 1905, and was responsible for Chalif being hired to teach folk dances at the Second Annual Convention of the Playground Congress of America in 1908.

Chalif was a prolific author and excellent businessman.... Once he realized that there was a wide market for folk dances he began to target that market, constantly supplying it with useful publications of both individual dances and larger compilations. He arranged over a thousand dances, and five of his textbooks have been translated into a number of foreign languages.... The dances were categorized according to their level of difficulty within the categories of 'folk,' 'national,' 'character,' 'historical,' 'aesthetc,' 'pantomime,' 'ballroom,' and, of course, 'ballet.'

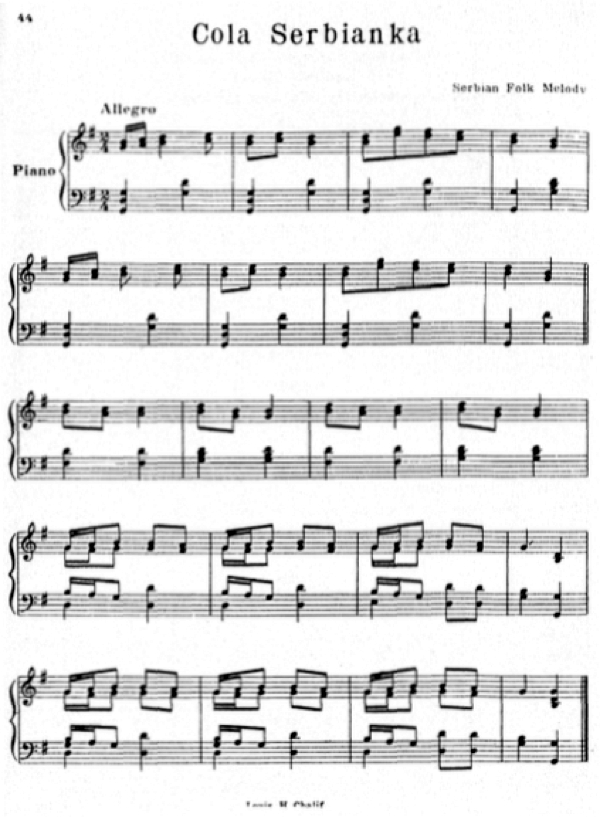

"To the best of my knowledge the first Balkan folk dances published in the United States are in Chalif's Folk Dances of Many Nations (1914), which included a 'Croatian Folk Dance.' Volume II published a 'Cola Serbianka [now known as 'Seljančica' – DB].'" Chalif likely learned this dance from an urban dancing master in Serbia.

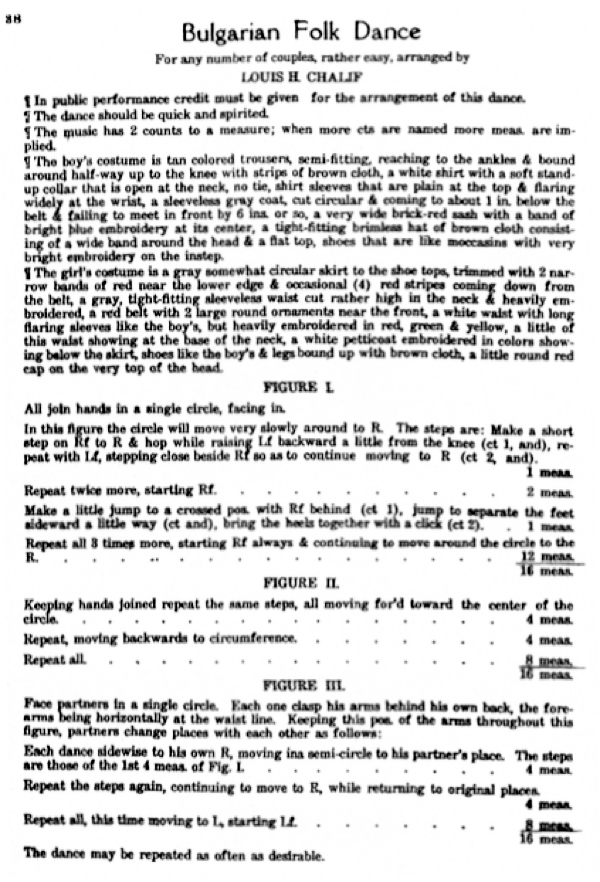

"The "Bulgarian Folk Dance" set to a "Hungarian Folk Melody" is among twenty 'slightly difficult dances.' This sample clearly shows the extent of the interpretive liberties of the era. The dance steps and the music were obviously treated as separate units. The fact that Bulgarians never danced to Hungarian tunes was not a concern for Chalif. This symbiosis was probably a matter of convenience. Most likely, Chalif learned the dance steps and in the absence of the appropriate tune he found a tune that 'matched' the steps."

In 1926, Chalif published two volumes of his "Folk Dances of Different Nations," which contained two dances still in the recreational folk dance repertoire. Volume 1 contained a "Russian Folk Dance" to a "Russian Folk Melody" very similar to what was later called Pletyonka. Volume 2 contained a dance Chalif claimed to have arranged to a traditional Russian song called Troika. According to Ron Houston's Folk Dance Problem Solvers (©1988 for Pletyonka and ©2000 for Troika), both 'dances' are of dubious origin. He could find no reference to either dance before Chalif's publications.

While Burchenal was travelling to Northern Europe to study how folk dance was being taught there, and Chalif was teaching Americans his brand of ballet-inspired European dance, traditional American folk dance, exemplified by the contra Hull's Victory and the round dance Heel and Toe Polka, found an unlikely champion in industrialist Henry Ford.

Traditional American dance, especially the relatively refined New England variety of quadrilles, contras, and European-based round dances, had been on the decline; due in part to the mass movement of rural dwellers to the cities to find better-paying jobs, and also to ragtime and jazz age dances and music, which made traditional music and dance seem passé.

By inventing the production line, Henry Ford made possible mass-produced, affordable automobiles, thus securing his position as one of America's richest men. Ford then turned his attention to reforming the country's wayward ways. He was raised on traditional dance, met his wife of 28 years at such a dance, and despised modern music, In 1926, he published a ..., Good Morning, produced with the expertise of dancing master Benjamin Lovett. It contained detailed instructions for square (quadrille), contra, and round dances that were popular in Ford's youth. Ford ordered his executives and their wives to regular Friday dances where Lovett would teach. Then Ford and Lovett organized a dancing school for children, wrote a manual for physical education teachers, hired an orchestra to produce records, and sent Lovett and his wife to teach in 31 colleges and universities.

History of RIFD in the USA – Phase 2

From Don Buskirk's website, Folkdance Footnotes.

Used with permission.

This page © 2023 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.