|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Israeli Culture

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

BACKGROUND

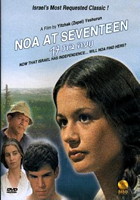

Information: A film review by Ron Houston, February 18, 1990.

REVIEW

Though the film was in color (predominantly blue and white), its socioeconomic attitudes were portrayed in black and white. The secondary theme of failing female dominance in the ubiquitous Jewish sexual wars complicated both the plot and the lives of its characters. On a deeper level, the film is a parable about the State of Israel pushed to decide between alliance with the Soviet Union or with America.

Though the film was in color (predominantly blue and white), its socioeconomic attitudes were portrayed in black and white. The secondary theme of failing female dominance in the ubiquitous Jewish sexual wars complicated both the plot and the lives of its characters. On a deeper level, the film is a parable about the State of Israel pushed to decide between alliance with the Soviet Union or with America.

On the one side were predominantly the older generation: socialist-communist, pro-Soviet, rural, communal, male, and emotional. Shraga loves Socialism because he, in effect, gave his life to the building of a Socialist kibbutz. He sacrificed his wife who, when the system failed, killed herself rather than fight, and also lost his daughter rather than accept her Mapai-nik husband. Shraga would rather see the kibbutz burn than abandon the old ways. He chooses to farm an impossible piece of land rather than live with hypocrisy. This group represents the Soviet Union and frequently wears red.

On the other side were predominantly the youth: idealistic, democratic, principled, urban, female-dominated, and pro-America. Aya and Uzi don't smoke, follow patriotic and democratic ideals blindly, and want to work on a democratic kibbutz. Hypocrisy lurks at the edges of this group and is especially prevalent in the sexual war: Aya won't sleep with Uzi but still says "I could make a man out of him. It would be very difficult, but I could." Uzi will sleep with Noa, but claims the highest idealism of his group. These youth represent America and frequently wear blue.

Caught in the middle is Noa. Above all, Noa wants to be an individual. She will drop out of school rather than conform. She eschews idealism for emotion and independent thought and will even forego further sex with Uzi because of his blind idealism. Privacy is more important to her than group cohesion, as demonstrated by the "diary scene" which opens the film. Noa serves as a parable for the State of Israel: she wants her autonomy. She wears alternately red and blue.

This contorted plot resolves as Noa chooses to remain in school. She doesn't want others with more education ever to control her life. Shraga chooses to work his farm. Only Meyer changes. He will no longer be the docile husband. He will not be forced out of his home. He will raise his children and ignore his shrewish wife. We aren't told the decisions of the Mapai-niks nor of the youth group.

This film shows the triumph of integrity, but the struggle wasn't that difficult. Noa chooses integrity over her foolish and venal friends. Shraga chooses integrity over living with people who won't have him anyway. Meyer chooses integrity over confrontation with his witch-wife. The obvious message is that Noa (and Israel), Shraga, and Meyer are better off with integrity, though alone.

As a literal reflection of Israeli culture in the 1950s, this film could destroy Zionism! Israeli women are portrayed as manipulative, self-serving, shallow, and domineering with no motive but to win their little domination games. The Israeli world view is polarized into America versus the Soviet Union with no middle ground, exemplified by the Biblical reference to Solomon's Judgment. Israeli debate and negotiation are no more subtle than out-shouting your opponent, with the loser suffering exile.

As a figurative reflection of Israeli culture, the film preaches the virtues of superiority through education, non-alignment, integrity, and quiet endurance.

DOCUMENTS

- Israel, a country.

- Ron Houston, an article.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.