|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Peruvian Dance and Culture

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

Peru is a dancing society. There is not one manifestation of life in Peru that does not involve some form of dance. In Peru, dance is a sublimation of everyday occurrences and deeds and of the philosophical and religious nature of the people. Dance in Peru is as rich as the society and it reflects the concepts and values that Peruvians have regarding the world and human life. It could be said that in Peruvian society, dance is an instrument of life because it not only contains the essence of life, but also contributes to the subsistence and continuity of the society.

Peru is a dancing society. There is not one manifestation of life in Peru that does not involve some form of dance. In Peru, dance is a sublimation of everyday occurrences and deeds and of the philosophical and religious nature of the people. Dance in Peru is as rich as the society and it reflects the concepts and values that Peruvians have regarding the world and human life. It could be said that in Peruvian society, dance is an instrument of life because it not only contains the essence of life, but also contributes to the subsistence and continuity of the society.

Dance reflects Peruvian society through its different phases of history. According to Peruvian ethnomusicologist Cesar Bolaños, the history of the musical and choreographic arts in Peru dates back 15,000 years. In remote times, nearly 2,000 years ago, it represented the creation of the Quechua people. These are better known as the Incas, the magnificent civilization of Peru that flourished there before the Spaniards came to the South American continent. Dance later assimilated the elements coming from the Western world, principally from the Spaniards who conquered Peru beginning in the third decade of the 16th century. The ancient Quechua people absorbed and transformed Spanish cultural elements into their own culture, creating new forms of dance and music.

Along with the Spaniards came the African Blacks, brought to work as slaves. These also influenced the physiognomy of Peruvian dance, producing more new forms of dance and music. These three cultural strains: Indian, Spanish and Black, are the primary sources from which Peruvian dance and music developed in history. The coming together of these strains, however, did not occur as a simple addition of elements; it was an intense cultural blending taking place over many years and historial circumstances that produced a new culture, different from original component cultures, with new forms, personality, and concepts. This new culture (originally referred to as Mestizo or Criollo, referring to its national character) constituted Peruvian culture. The process of cultural "mestizaje" (blending or mixing) was the original base for a rich dance and music tradition that has developed with such character to this day.

The function of dance is omnipresent in Peruvian culture. It is part of the regular cycle of life, including birth, puberty, marriage, and death. The symbolic content of dance is drawn from the complex of religious and mythical beliefs of the people, from the patterns of relationships between the individuals and their environment, and from their feelings of identity with their society. Through history, dance manifestations have evolved in deep correlation with the lives of people. Dances have varied their forms and accents according to social changes and those featuring modes that no longer exist have disappeared or are dying out. Some forms of dance that have lost their social function have remained as gorgeous pageantry.

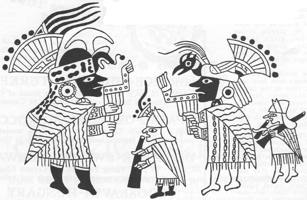

A general classification of Peruvian dances should be done according to their historical origin: in (1) dances of precolonial origin, and (2) dances of postcolonial origin. Pre-Columbian dance and music is that created by the ancient inhabitants of Peru (pre-Inca and Inca cultures), prior to the advent of Western civilization: starting approximately 15,000 years ago, much of this dance and music remained unaffected by the Spanish culture through the centuries and can still be seen today. We know about pre-Columbian dance and music through archeological sources, mainly pictographic figures found on pottery, such as scenes of people holding hands in circles and showing dance poses as musicians are playing instruments. With the advent of the Inca Empire around the year 1,400 CE, dance and music underwent a revitalization, because the Inca emperors were very fond of dance and music and included these in their royal ceremonies.

A general classification of Peruvian dances should be done according to their historical origin: in (1) dances of precolonial origin, and (2) dances of postcolonial origin. Pre-Columbian dance and music is that created by the ancient inhabitants of Peru (pre-Inca and Inca cultures), prior to the advent of Western civilization: starting approximately 15,000 years ago, much of this dance and music remained unaffected by the Spanish culture through the centuries and can still be seen today. We know about pre-Columbian dance and music through archeological sources, mainly pictographic figures found on pottery, such as scenes of people holding hands in circles and showing dance poses as musicians are playing instruments. With the advent of the Inca Empire around the year 1,400 CE, dance and music underwent a revitalization, because the Inca emperors were very fond of dance and music and included these in their royal ceremonies.

Archaeological sources for pre-Columbian dance and music are supplemented by written descriptions by such early chroniclers as Garcilaso de la Vega and Felipe Guáman Poma de Ayala, both of whom were born of Inca mothers to Spanish fathers. Garcilaso described Inca instruments and their method of performance, their sound and their significance, as well as the technical features and functions of Inca music and dance. He reports that the Incas (rulers and populace alike) had a smooth and stately style of dancing, without leaps, jumps, and the like. He informs us that only men danced. In large groups (200 to 300 people), dancers stood side by side and held hands or passed one arm around around the other's waist and danced in long lines. In his book, "Royal Commentaries of the Incas," published in 1609, he describes how Inca soldiers fighting during the conquest came marching back into Cuzco, their weapons in their hands, dancing to celebrate the deeds of the Incas in war. He informs us that "these dances declared the greatness and excellence of the Incas in battle, their skill and perseverance, their patience and kindness in suffering the insolence of the enemy, their clemency to the vanquished, their prudence and wisdom" (Vega 1871, 1609: 279).

Garcilaso also tells us how the festivities that followed the triumphal entrance of the soldiers and the worship in the Temple of the Sun were impressive occasions for dancing and singing to the accompaniment of drums and flutes (clay or shell), trumpets, gongs, clappers, seed rattles, bronze rings and various kinds of pipes, and these celebrations would last, amidst eating and drinking, from several days to a month. Garcilaso reports that these celebrations also featured dramatic presentations and tragedies on feats of past kings and other heroic themes and comedies with agricultural or homelike themes. He describes these dramas as narratives, or dialogues sung by one or two persons with an assisting chorus. He indicates that the parts were played or sung by nobles and military officers, sometimes by the chief Incas themselves, and that they were interposed as part of public dances. He also notes that there was as much dancing and singing at those religious fiestas (with many days of processionals and rites) as at the agricultural rites (Vega 19960, 1609:333-4).

Dances of postcolonial origin emerged after the Spanish conquest of 1532, resulting from the merging of the European with the Indian culture. This mingling, from the 16th century onward, constitutes the process of mestizaje, whose outcome is the mestizo dance and music. Acculturated Indian people adopted and modified European instruments, poetry, musical systems and dances, as well as created others to suit their customs and beliefs. Syncretism (the amalgamation or attempted amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought) was the definitive character of the new forms. This feature is evident today in many Indian rites and ceremonies and in the dance and music associated with them. For example, K'Chanchis, a popular Andean dance, is danced to pentatonic (relating to, based on, or denoting a scale of five notes) melodies with songs with Christian lyrics translated into Quechus, the Indian language.

The cultural transformation, retranslation, and integration of cultural elements not only created new forms but, more significantly, created new functions. Syncretic dances and music symbolized things of another universe. For example, the Catholicism of the Indians only faintly resembles that ot the Spaniards, as evidenced in Indian religious festivities, such as Corpus Christi (Christmas) in which even baby Jesus becomes "Niño Manuelito." Another example is the new symbolism of the Spanish bullfighting that became the "Yawar Fiesta" or "Festival of Blood" for the Indians. These illustrate how, with acculturation, not only the forms by the content of the dance, costume, and paraphernalia assumes a new function, reflecting the new Indian universe.

Another important element comprising postcolonial dances was the Black influence. African Blacks were brought by the Spaniards as slaves since the very beginnings of the conquest. These settled mainly on the Coast of Peru where they developed a rich dance and musical tradition that came to be known as Afro-Peruvian folklore, in which Indian and Spanish elements were assimilated into their African heritage.

Successive contacts with other European cultures further influenced mestizo dance and music. On the Peruvian Coast and in some lower elevations of the Andes, this gave rise to the so-called "criollo" dance and music, now representative of urban mestizaje and exhibiting a national character.

Today, Peruvian dances can be classified geographically in three main areas and to these geographical areas correspond different ethnic, historical, and sociological backgrounds. These areas are the Coast, the Andes, and the Amazon. Those of the coastal area show more Hispanic and Black influence. As the mountains become higher, Hispanic and Black elements weaken and Indian elements begin to predominate. Dance and music of the Amazon area is the least studied of them all. We know that the Incas did not colonize most of the population living in these tropical forests. Nevertheless, this area shelters more than thirty aboriginal groups, speaking a variety of languages.

Aside from the historical and geographic criteria mentioned for classifying Peruvian dances, a more meaningful criterion would probably be to classify according to content and significance, that is, according to the role they play in society. Basically: (1) religious dances, (2) totemistic dances, (3) war dances, (4) satirical dances, (5) pantomimic dances, (6) amusement dances, (7) agricultural dances, and (8) processional dances.

THE ANDES

Andean dance and music today represent two major types: the Quechua and the Aymara.

The Quechua

The Quechua are the Indian descendants of the Incas, their dance and music often being described as Inca. It is the most widespread Andean music and the one that exhibits the richest tradition. Quechua language, and like their Inca ancestors, are famous for their terrace cultivation and irrigation canals, their breeding of llamas, alpacas, guanacos and vicunas, their woven materials, pottery, and, above all, their social constitution with its system of "allus sor clans" and their remarkable organization of work. The distinctive quality of Inca dance and music survives in 20th century Quechua music that can be distinguished from the music of other Peruvian Indians.

The Quechua are the Indian descendants of the Incas, their dance and music often being described as Inca. It is the most widespread Andean music and the one that exhibits the richest tradition. Quechua language, and like their Inca ancestors, are famous for their terrace cultivation and irrigation canals, their breeding of llamas, alpacas, guanacos and vicunas, their woven materials, pottery, and, above all, their social constitution with its system of "allus sor clans" and their remarkable organization of work. The distinctive quality of Inca dance and music survives in 20th century Quechua music that can be distinguished from the music of other Peruvian Indians.

Their dance and music relate to most activities of the Quechua life, the most popular being agricultural and love dances and songs. their songs may be sung in either Quechua or in Spanish, or in alternation of both. Their music is characteristically pentatonic, and generally consists of four or more musical phrases of short duration repeated throughout. The oldest and most typical musical instrumentalist, the "quena" (a flute made of cane, bone, or wood) dates back to the pre-Inca periods and is one of the oldest instruments known today. Other instruments are panpipes and drums, particularly a small drum called "tinya," played sideways to the musician.

Their dance and music relate to most activities of the Quechua life, the most popular being agricultural and love dances and songs. their songs may be sung in either Quechua or in Spanish, or in alternation of both. Their music is characteristically pentatonic, and generally consists of four or more musical phrases of short duration repeated throughout. The oldest and most typical musical instrumentalist, the "quena" (a flute made of cane, bone, or wood) dates back to the pre-Inca periods and is one of the oldest instruments known today. Other instruments are panpipes and drums, particularly a small drum called "tinya," played sideways to the musician.

The main dance and song form of the Quechuas is the Huayno. This accompanies almost all occasions in their lives It is the ost popular dance-song form in the Peruvian Andes. The Huayno can have a lyrical or joyful character, and can be solemn or playful, depending on the occasion in which it is sung.

The dance is a semi-open couple dance, done in large groups. Partners do not hold each other, though they sometimes hold hands or onto each other's waists. They relate to each other mainly by facing, changing places, crossing, etc.

The Aymara

The other major Andean dance and music tradition is the Aymara, also called the Colla. These Indians were conquered by the Incas, but maintained their own musical tradition that survives to this day. This group is located in southeast Peru, mainly in the area of Puno, a high Andean plateau approximately 2,500 feet above sea level, where Lake Titicaca is located, between Bolivia and Peru. The most characteristic types of Aymara music are instrumental, played by ensembles of the "sicu" (traditional Andean panpipe) of different pitches. Aymara panpipe ensembles may include panpipes from one to four feet long and up to twenty-five musicians. Aymara music is more melodic than Quechua, while Quechua music is more rhythmic. There is a preference for triple rhythm and less rhythmic variation than in Quechua music, that typically may vary among 2/4, 3/4, and 4/4 meters.

The other major Andean dance and music tradition is the Aymara, also called the Colla. These Indians were conquered by the Incas, but maintained their own musical tradition that survives to this day. This group is located in southeast Peru, mainly in the area of Puno, a high Andean plateau approximately 2,500 feet above sea level, where Lake Titicaca is located, between Bolivia and Peru. The most characteristic types of Aymara music are instrumental, played by ensembles of the "sicu" (traditional Andean panpipe) of different pitches. Aymara panpipe ensembles may include panpipes from one to four feet long and up to twenty-five musicians. Aymara music is more melodic than Quechua, while Quechua music is more rhythmic. There is a preference for triple rhythm and less rhythmic variation than in Quechua music, that typically may vary among 2/4, 3/4, and 4/4 meters.

Q'canchi

Q'canchi is a very old dance from the Quechua tradition. It is danced in the religious ceremonies of the Feast of the Holy Cross (in early May) and St. Sebastian's Day (January 20). It commemorates the Inca governors from the time of the Empire. The dancers are preceded by the "Warajok," a figure of authority who carries a silver staff. In the religious feasts, pentatonic melodies are sung with Christian texts translated into Quechua. So, this dance, as danced today, features the characteristic of syncretism.

The second Andean dance is the Huayno. This also is danced in Cuzco on joyful occasions. The dance and the song lyrics often include love themes expressed with humorous poetry.

Casarasiri

Casarasiri is a festive dance from the Aymara tradition, danced by couples who wish to be married. This dance shows European influence over Indian elements. The name is an Aymaran derivation of the Spanish word "casar," which means "to marry." Joyful groups of couples do the Casarasiri, expressing their expectations and feelings for getting married. This is one of the most popular traditions in Puno.

THE AMAZON

These dances of the aboriginal groups of the Amazon forests dramatize myths, codify their laws, and represent their cultural and religious history. Rites associated with the life cycle and fertility are extremely important. These people are hunters, fishermen, and farmers. Their rites are accompanied by dances, music, and songs. The musical instruments include panpipes, trumpets, flutes, and rattles.

The music of most of the forest Indians is characterized by imprecise pitches that sound like quarter-tones, and by unmeasured styles. Singing is commonly wordless.

THE COAST

The dance and music of the Coast is representative of Peruvian dance mestizaje. That is, it contains the elements of the three major sociocultural groups that mingled in Peruvian society – Indian, Spanish, and Black. This cultural mingling can be seen in various combinations, often with the predominance of either Hispanic or Black over an Indian base.

Coastal music, though retaining Quechua musical elements, is distinguished from the latter by its scales and its harmonic accompaniment on harps, guitars, and other guitar-like instruments &150; "láud" (a plucked string instrument), "cuatro" (a lute), "guitarrilla" (a mini guitar), and a simple triple rhythm of highland Quechua music. Harmony was introduced as a result of the harp and guitar accompaniment; the diffusion of European scales led to extra notes being added to the closed pentatonic system of Andean music.

The two major influences in Peruvian Coastal dance and music are the Hispanic and African. These two have developed into the two main genres of Coastal Peruvian dance and music: Criolla and Afro-Peruvian.

Criolla dance and music is the popular form for most occasions and celebrations. It accompanies many events, such as birthdays, weddings, births, religious events (such as street processions), lyrical occasions (such as the loss of one's beloved), etc.

This genre exists principally in the Coastal urban centers. Because of the leading role of these centers in the present modernization of the country, this type of dance and music tends to become the national trend.

The most popular Criolla dance and music forms are the Vals and the Marinera. The Vals is a social couple dance done in closed ballroom position. It is danced at almost every social celebration in Peru. Though it is mostly a Coastal genre, it has now spread to the rest of the country, and regional interpretations can be found.

The Vals

The Vals is originally from Lima, where it appeared around the year 1875. Various influences have merged in its formation, of which the Viennese Waltzis the most obvious. Also, it was influenced by the Andean Yaravi, a melancholic song type, and the Spanish Jota, a lyrical song type. Later, it developed a festive character as well.

The Vals is originally from Lima, where it appeared around the year 1875. Various influences have merged in its formation, of which the Viennese Waltzis the most obvious. Also, it was influenced by the Andean Yaravi, a melancholic song type, and the Spanish Jota, a lyrical song type. Later, it developed a festive character as well.

The classical instrumentation for the Vals consists of two acoustic guitars, one playing the main melodic line and the other playing chordal accompaniment, and the "cajon" (a wooden box with a sound hole in the back) providing percussion accompaniment. For this, the musician sits on the "cajon" and strikes it between his legs. There are from one to three vocalists as well. Hand clapping also accompanies Vals songs.

The lyric of the Vals songs reflect the life of the people. Most frequent themes are love, drama, nationalism, and historical events. the song texts dealwith current events and love stories. Themes are often sentimantal in nature, lovesongs of melodramatic character abound, but there also are many of festive, good-humored, satirical of comic character.

The Marinera

The Marinera is one of the most representative dances of Peru. For its popular appeal, it has been called the "national dance of Peru." It is an open couple dance, in which dancers never touch. It is usually danced by one couple at the end of a special event of celebration. This confers to the dance an enhanced importance, because it is deemed the "grand finale" of many special events.

The origins of this dance are still obscure. There is disagreement among scholars as to its Hispanic or African origin. It is known to have derived from an older Peruvian dance called Zamacuece from which the Argentinian Zamba and the Chilean Cueca also originated, nearly three hundred years ago. At present, it is most representative of the Peruvian mestizaje and it is danced by mestizo Indians, Hispanics, and Blacks, each offering its own version.

The Marinera is a courtship dance, happy and festive, with humorous, bawdy lyrics with many double meanings. In its courtship character, it expresses the people's conceptions about the male-female relationship. The woman express coquetry and being demure, the man ribaldry and certain aggressiveness. In general, the rule is that the dancers must maintain elegance and decorum. The end symbolizes the triumph of love.

The Marinera is danced only by those with the necessary expertise. It is not done by everyone, as is the Vals. It usually is danced once, at the end of an event, by one couple, while the rest of the participants circle the dancers and provide an ambience for the dancers by hand clapping, and verbally supporting and complimenting the dancers with calls and encouraging phrases. Sometimes, a second couple dances after the first one has finished, or, nowadays, at the same time, though this is not the ideal.

THE AFRO-PERUVIAN TRADITION

The Afro-Peruvian tradition began with the first Africans that were brought to Peru by the Spaniards. The Black presence was notable primarily on the Coast. Concentrations of Blacks were to be found in the major fertile river valleys along the Coast, working in the valleys and farms mainly on the southern Coast. As early as the 1540s, religious brotherhoods or societies (called "cofradias") were begun among the Blacks (Tomkins, 1981:20). These concerned themselves with the spiritual and physical welfare of their members and thus created a certain degree of community. As the slaves' identification with former ethnic groups waned with succeeding New World generations, a new Afro-Peruvian community and culture arose. Abolition of slavery was declared in 1854, and was finally realized in 1865 under President Ramon Castilla.

The most important result of these political and moral struggles was a greater sense of national unity – reflective of the process of mestizaje. The blending of musical characteristics derived from the Hispano-European, Indian, and African traditions replaced much of the music of the slaves and evolved over several centuries to constitute the Afro-Peruvian tradition.

Dance and music of the Blacks of Peru is characterized by its brilliancy and intensity of style. The music is characteristically in 6/8 meter with much syncopation and rhythmic variation. Percussion instruments abound, of which the "cajon" is the most popular. The "cajon" appears to have been invented by the Blacks, who show great dexterity in the playing of this instrument. Another instrument peculiar to the Blacks is the "quijada" (donkey's jawbone), which is struck on the side to cause the teeth to rattle in their sockets. Guitars, voices, and hand clapping also are used in this genre.

Dance and music of the Blacks of Peru is characterized by its brilliancy and intensity of style. The music is characteristically in 6/8 meter with much syncopation and rhythmic variation. Percussion instruments abound, of which the "cajon" is the most popular. The "cajon" appears to have been invented by the Blacks, who show great dexterity in the playing of this instrument. Another instrument peculiar to the Blacks is the "quijada" (donkey's jawbone), which is struck on the side to cause the teeth to rattle in their sockets. Guitars, voices, and hand clapping also are used in this genre.

Afro-Peruvian dance and music are generally festive and joyful, although there also some laments or sad songs with a very melancholic flavor. The texts of the songs speak about elements of everyday life, such as food, housekeeping, baby raising, etc. They also have love and erotic themes. Some of the laments sung today refer to the slave times.

Afro-Peruvian dance is characterized by agile movements of the shoulders. The body position is flexed and relaxed for the dancers, the singers, and the musicians.

The most popular Afro-Peruvian dances at present are the Festejo and the Alcatraz.

The Festejo

The Festejo is a lively open couple dance done at most social celebrations of the Blacks. It exhibits many sudden turns, jumps, and brisk movements. It is a dance done to a fast tempo and is usually accompanied by calls and verbal expression from the dancers.

The Alcatraz

The Alcatraz is of an erotic nature. It is a couple dance in which the dancers bear lit candles and try to burn a piece of paper (saturated with a flammable solution) that they fasten at the back of their waists. This paper is called "alcatraz." The partners take turns in doing this. With agile and precise hip movements, the dancers try to avoid getting their "alcatraz" burned. Rather than a serious ritualistic erotic character, the dance of the "alcatraz" has a festive and light erotic flavor.

DOCUMENTS

- Americas, a region.

- Latin America, a region.

- Peru, a country.

- South America, a continent.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, June/July 1987.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.