|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Ragtime Dance History

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

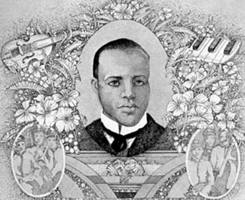

The beginning and end of the so-called "Ragtime Era" can be measured almost to the day – a twenty-year period beginning with Scott Joplins "Maple Leaf Rag" in 1898, and ending with the tragic death of Vernon Castle in 1918.

The beginning and end of the so-called "Ragtime Era" can be measured almost to the day – a twenty-year period beginning with Scott Joplins "Maple Leaf Rag" in 1898, and ending with the tragic death of Vernon Castle in 1918.

It all began when a scrupulously honest salesman by the name of John Stillwell Stark, who made his living selling anything he could to the farm community around Sedalia, Missouri, discovered a new and exciting form of music pouring out of a saloon in the thriving red-light district. It was Scot Joplin playing his creation, "Maple Leaf Rag." Stark had an idea and signed Joplin to a contract, paying him a penny for every sheet of Joplin's music that he could publish.

The wise and honest business arrangement ensured Joplin's fame and fortune and set the music world on a new course that was to lead American culture into the new 20th Century. The new "Ragtime" music was an instant hit and spread across the northern and eastern United States in a frenzy of regional styles. Even jazz, developed in New Orleans, Louisiana, far from the recording studios of the east, was a local form of Ragtime that took its own route to fame following World War I and the rise of the "Roaring 20s."

With thousands of composers creating the new Ragtime music everywhere, it quickly followed that someone would dance to it. And dance they did – funky dances, popular with the lower classes (and the upper classes, too, when they could sneak into them). Animal dances were early favorites, with now-famous names such as "Turkey Trot" and "Grizzly Bear," gleefully and unabashedly mimicking the imagined frolics of their namesakes.

America had a new middle class emerging about then, thanks largely to Presidents Roosevelt and Taft, whose trust-busting campaigns allowed new competition and created new wealth where there had been none before. These "nouveau riche" wanted nothing to do with the antics of those from whom they had so recently been a part and sought vainly for something to suit their new station in life.

And they waited. For what, they did not know, until it happened in the form of a fresh, young couple who had made their mark in Paris as nightclub dancers with a sophisticated new style of dance. They were Vernon and Irene Castle. They arrived in 1911, and they took America by storm.

And they waited. For what, they did not know, until it happened in the form of a fresh, young couple who had made their mark in Paris as nightclub dancers with a sophisticated new style of dance. They were Vernon and Irene Castle. They arrived in 1911, and they took America by storm.

The Castles were everything the new middle class was waiting for – sophisticated, stylish, handsome, charismatic – perfect. Their dance was smooth, dignified, and graceful and everyone could look good doing it. As their fame spread, they toured the country, giving lessons and performances from Chicago, Illinois, to Miami, Florida, to New York City, New York. Vernon's fee for teaching some of the country's wealthiest people topped $100 per hour, an incredible figure in 1914, or anytime, equivalent to nearly $3,000 per hour today [2020]. The Castles amassed, and spent, a tremendous fortune. Irene Castle set women's fashions for decades and caused major changes when she shortened both her skirt and her hair. Hundreds of thousands of women followed suit and, for the first time in modern history, women showed their ankles.

Vernon immediately introduced the dance movement of backing the lady, something that could not be done in a floor-length skirt, and women have danced backward ever since.

The list of Ragtime dance created and introduced by the Castles is remarkable and many of them are still with us in one form or another. The One-Step, so-called because it takes one step on each beat, was the most popular, with an exhilarating, driving quick tempo. The dance evolved into the Peabody in the 1920s and later into the Quick-Step. The sultry and "immoral" Tango was polished by the Castles into a playful, flirtatious dance that was perfectly acceptable to the new dance world and it has evolved ever since into an important part of the American ballroom dance repertoire. The Polka likewise received a make-over by the Castles. Films of them performing the dance indicate a remarkable similarity to the so-called Polish Polka as found in cities like Chicago and Detroit, Michigan, and Cleveland, Ohio – but nowhere in Europe. The remarkable Maxixe was to many the most interesting and challenging of all the Ragtime dances, in reality a Parisian adaptation of a Brazilian version of a Bohemian Polka. Though its popularity was brief (starting with the Titanic and ending almost as soon), its rich repertoire of figures and Latin movement later evolved in Brazil into the dance we know as Samba.

There were a number of ethnic dances and music created by composers who had no clue of the origins of their music and it showed: Persian, Chinese, Russian, Hungarian, and Turkish music were introduced to the Ragtime music scene – most of it bearing no resemblance to the real thing.

In spite of that, there were some very authentic ethnic dances introduced, though frequently misidentified. At least two well-known Polish dances were introduced as either Russian or Hungarian. Americans were getting too cocky. They thought they knew it all.

The Castles only performed in America from 1912 to 1916. When England was pulled into World War I, Vernon, an English citizen, enlisted in the Royal Air Force. In an act of bravery, he took the front seat of a training plane as a flight instructor and died when the plane crashed in 1918. The student in the rear seat survived.

So ended the magical Ragtime Era. With the Castles no longer there to lead it, Ragtime gave way to jazz, as the New Orleans musicians spread north following the closure of that city's famed Storeyville red-light district.

Though the Ragtime Era ended, Ragtime music never did. There has never been a time since then that someone was not composing new music. Today, Ragtime music and dance are alive and well with Ragtime orchestras playing at Ragtime festivals across the country. California is now one of the major centers of Ragtime music and dance. Festivals up and down the state are eagerly attended by skilled musicians and dancers and by wildly appreciative audiences who happily soak up this very American art form.

DOCUMENTS

- Choreogeography: American Ragtime to Swing, an article.

- Richard Duree, an article.

Used with permission of the author.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, October 2002.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.