|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Tahiti in Music and Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

Today, dance seen in Tahiti is of two kinds: popa'a (European-style) and 'ori Tahiti (or t m r, traditional Tahitian dance). Popa'a is commonly seen at parties, large feasts, balls, and in Papeete nightclubs. It is accompanied by Western music in terms of melody, rhythm, and harmony. 'Ori Tahiti, found in these settings, tends to be a hybrid of traditional Tahitian dance movements and the Western notion of dance partners. 'Ori Tahiti is generally characterized by group presentation, choreographed, rehearsed movements, traditional musical accompaniment and/or singing, the wearing of special costumes, and performance at predetermined occasions. The music is an integral part of the dance, and is generally played on traditional instruments.

Today, dance seen in Tahiti is of two kinds: popa'a (European-style) and 'ori Tahiti (or t m r, traditional Tahitian dance). Popa'a is commonly seen at parties, large feasts, balls, and in Papeete nightclubs. It is accompanied by Western music in terms of melody, rhythm, and harmony. 'Ori Tahiti, found in these settings, tends to be a hybrid of traditional Tahitian dance movements and the Western notion of dance partners. 'Ori Tahiti is generally characterized by group presentation, choreographed, rehearsed movements, traditional musical accompaniment and/or singing, the wearing of special costumes, and performance at predetermined occasions. The music is an integral part of the dance, and is generally played on traditional instruments.

In ancient Tahiti, the drums used for dance accompaniment were called pahu 'upa'upa. These were single-headed drums of varying sizes, placed on the ground and played with open hands. Generally, they were made of single hollowed-out logs. Additionally, there were bamboo slit drums, made of closed segments of bamboo with narrow slits cut horizontally. The only other instrument known from those times was the bamboo nose flute.

In modern ensembles, there are four different types of drums, as well as the ukelele and guitar (both imported instruments). The drums include the to'ere, the fa'atete, and the pahu, and occasionally the pahu tupa'i rima.

In modern ensembles, there are four different types of drums, as well as the ukelele and guitar (both imported instruments). The drums include the to'ere, the fa'atete, and the pahu, and occasionally the pahu tupa'i rima.

The bamboo to'ere (slit drum) has been replaced with one hollowed out from a single log. Of various sizes, they are struck on the sides with sticks made of soft wood. Several tones are produced because of the varying thickness of the drum at the top, bottom, and sides. A full, resonant is produced if the drum is hit near the center, while a higher, tighter sound is made when the drum is hit on either end.

The fa'atete is a single-headed, membrane-covered wooden drum. The head is attached to the drum with sennit (coconut fiber). All either have footed bottoms or are set on pedestals to allow the resonating chamber to sit off the ground. Traditionally, these drums are played with the hands, but now they are often beaten with two soft wood sticks.

The pahu is a double-headed drum with a body of wood. The diameter of the head is approximately the height of the drum, ensuring good tone. Set on its side on the ground, the drum is beaten with a soft wood stick. The pahu tupa'i rima is similar in construction to the fa'atete drum, but is larger and played with the hands.

Emphasis in Tahiti is on group (versus individual or couple) dancing. In this way, children are exposed to dance at a very young age, and on multiple social occasions. Through this exposure, they learn what songs go with what movements, which movements are male and which are female, and to associate dancing with large groups of people. As they grow older, they attend schools and/or churches that organize children's dance groups. Later still, they may join amateur groups formed for performance and competition (especially for the July Fete), and may even join in one of Tahiti's eight professional groups.

CONTEMPORARY DANCES

No historical reference has been found for Tahiti's four dance genres, 'ote'a, 'aprima, hivanau, and pa'o'a. Of the sixteen mentioned in historical texts, none are performed in Tahiti today.

'Ote'a

'Ote'a is a group dance organized around a central theme (usually based on an element of nature, such as the wind, a flower, an island legend, or a person) and performed in well-defined columns of sexually-segregated dancers. Though the columns usually face the audience, they are not static, and can move or interweave to form a "V," "X," or asterisk pattern.

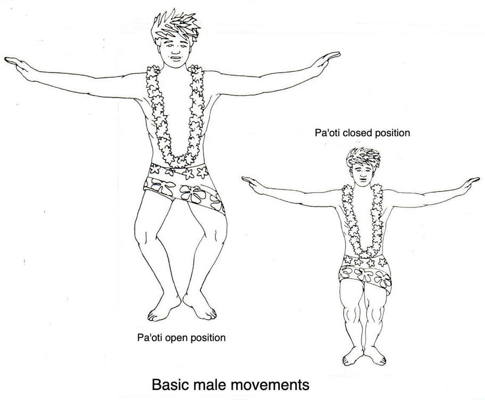

The dance movements are sex-specific. Male movements include, but are not restricted to, the pa'oti, tu'e, horo, and 'otaha. The pa'oti is the characteristic male movement and depends exclusively on the legs, that are opened and closed in a flapping or scissor-like fashion. The step is done with the heels together and either flat-footed or slightly on the balls of the feet. Importantly, the hips do not move. Legs are opened and closed at the rate dictated by the rhythms of the drum accompaniment. The tu'e is a forward kick, repeated quickly on alternating feet. Often, the arms accent the movement by pushing down with the fists repeatedly. The horo is a spirited running step, and the 'otaha, used for forward locomotion, is a one-legged hop performed with the unweighted leg extended to the side or backwards, and arms are extended to the side for balance.

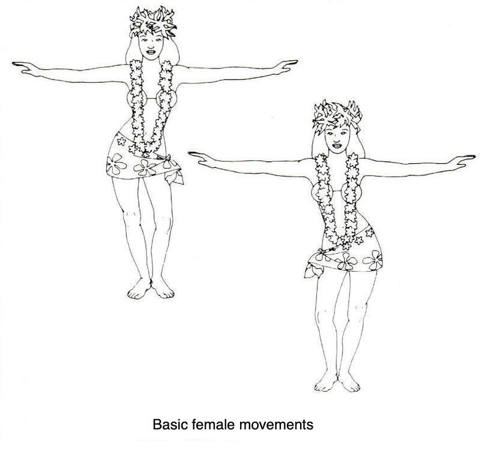

Female movements center around the hips. The hip movement is naturally created by bending and straightening one knee after the other. As the knee never totally straightens out, the hip sway is exaggerated. Feet are flat on the ground with heels together and toes slightly spread apart. The motion can be modified by adding a tight circular pelvic motion, or by throwing the hip strongly to one side or the other for accent. The hips are never rotated forward and back, and the shoulders and upper torso remain stationary.

Arm gestures are not used to tell a story. Rather, they are very abstract and tend to be large, angular, and abrupt. Male and female arm movements are basically the same, with arms held high and away from the body. The two basic positions are out to the side at shoulder level and in a "rest" position, with hands on the hips.

Accompanying the dances is a drum ensemble consisting of three to'ere (slit drums), one fa'atete (single-headed drum on a pedestal), and one pahu (double-headed drum). The rhythmic patterns provided by the drummers are many and varied, serving to cue the dancers to changes in the dance patterns and to provide tempos of the dances.

Costumes for the 'ote'a include a more (a "grass" skirt, actually made of shredded tree bark or other materials), a hatua (dance belt), a flower or shell lei around the neck, a tape'a titi (breast covering for the females), sometimes a tahei (abbreviated shawl) for the men, flowers or elaborate headdress, and 'i'i (hand-held whisks).

The more is worn low on the hips for the females, and serves to accentuate their hip movements. Generally, it reaches to the ankle. Men wear the more at the waist and have it cut just below the knee. The woman's breast covering can be made of two polished coconut halves fashioned into a bra, or of a normal strapless bra covered with tapa cloth (made of bark) and decorated with shells or feathers. The headdresses, when used, come in wide varieties, some up to two or three feet tall.

'Aparima

'Aparima are dances that use the hands to tell stories. There are two forms: 'aparima vava (the mute 'aparima), in which the story is told only through danced pantomime and the dancers accompanied only by rhythm; and 'aparima himene (the "sung" 'aparima), in which narrative gestures accompany a sung text and stringed instruments join the drums to accompany the dance.

In 'aparima vava, scenes from daily Tahitian life are pantomimed. Attention is focused on hand movements, and use of hand props is common. There is very little other movement. In fact, often these dances are done in a kneeling position. Music is of secondary importance, used only to accentuate the story. The rhythms, played by the same type of drumming ensemble that accompanies the 'ote'a, are often repetitive and low intensity.

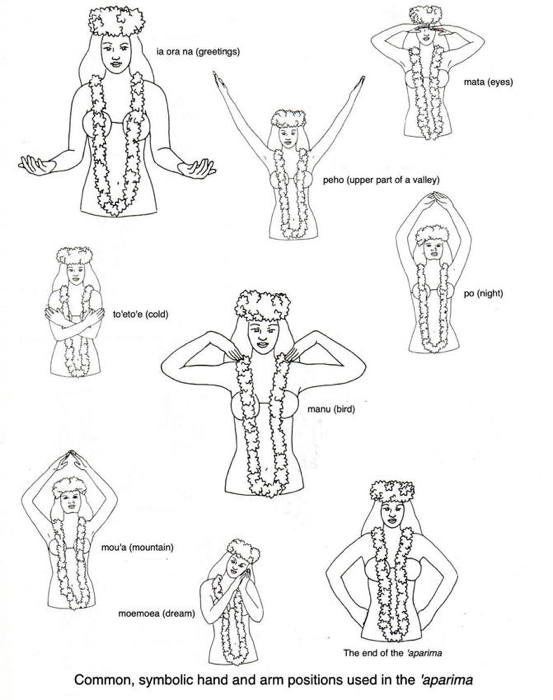

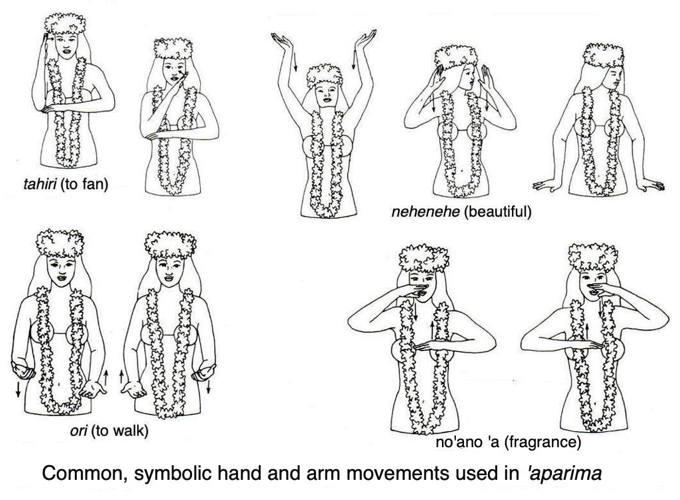

'Aparima himene centers more on island legends, thoughts and feelings, rather than on daily life. The dance compliments the song text and provides supplemental narration through movement. Hand movements can be mimetic, ornamental, or symbolic. The symbolic are the most difficult to interpret and often require some knowledge of the "vocabulary." Even then, there can be difficulties because hand movements are not fully standardized and tend to be somewhat dependent on the context of the story in which they appear.

The movement of the hands and wrists is relatively stiff when compared with similar gestures of other Polynesian groups. For male dancers, the fingers, hands, and lower arms move as one unit.

Both types of 'aparima are short (40 to 60 seconds long), and in a group performance, tend to be grouped together. The opening dance would be to a lively rhythm and serve to move the group to the performing area. The last dance in the series would be performed to a slow rhythm and used to move the group off the "stage."

Costuming for the 'aparima is quite different from that of the 'ote'a. Primarily, it consists of the pareau, a piece of cloth wrapped into short "pants" for the male dancers or a skirt for the female dancers. The female also wears a bra of matching fabric or, less commonly, of coconut shell halves. Flowers are usually worn around the neck. the head ornament, the hei uipo'o, is usually a fern wreath, but it can be made of coconut fronds and decorated with flowers. Additionally, many props, such as household utensils, and fishing and hunting implements are used in 'aparima dances.

It should be noted here that masks are never used in Tahitian dances. This is consistent with the Polynesian belief in the sacredness of the head and the Tahitian preference for beautifying rather than hiding the head and face. Also, the eyes are very important in some dances. They often follow the hands in the 'aparima and are sometimes used to make contact with the audience.

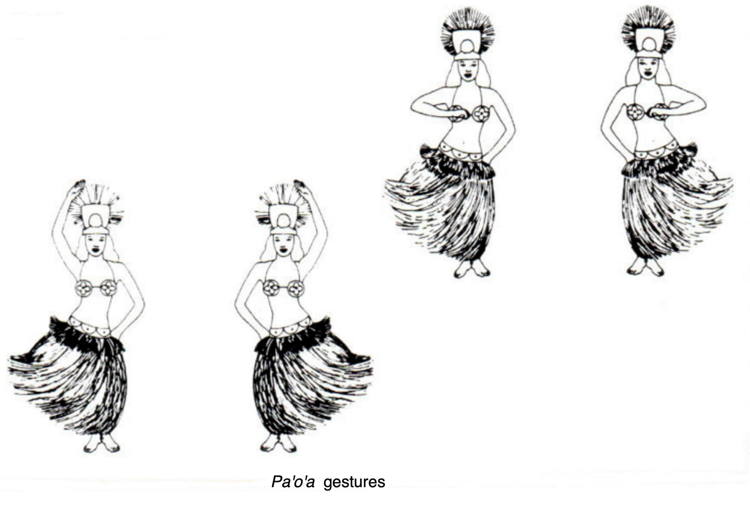

Pa'o'a

Pa'o'a is said to have originated with groups of women when they made tapa cloth. They sang as they worked, with a solo/chorus alternation. Sometimes, one of the women would spontaneously jump up to dance for a short while.

Features that distinguish this dance from the other three 'ori Tahiti include the use of a small performing group and the high degree of improvisation allowed. There are only four performing parts for this dance: a male solo vocalist, a mixed group of people forming the chorus, a drumming ensemble, and one or two dancers. The group beats out rhythms on the ground (or on their thighs, depending on the circumstances), and there is a great deal of interaction between the solo vocalist and the group. The text of the songs is of primary importance. The chorus' responses are chanted, and their beating out rhythms on the ground provides a steady rhythm for the dancer(s) and soloist.

The dance begins with the setup of the rhythmic pattern. Then the male soloist starts his recitation. Following this, a female dancer or couple stands and begins their dance improvisation. The basic movements of the dancers are the same as in 'ori Tahiti, but with more emphasis on mobility.

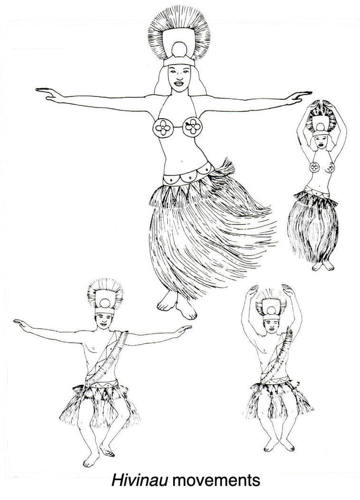

Hivinau

Hivinau is a happy dance, originally done at celebrations, characteristically in a double circle formation with the musicians and group leader in the center. The leader calls out a short verse and the rest of the group responds in "heightened speech" (somewhere between talking and singing). The chorus response is a distinctive feature of this type of dance. The final line of the leader, answered by instruments only, signifies the end of the dance. The text of most of the hivinau is concerned with fishing and the sea.

The concentric circles are usually all male or all female, and can move either together or in opposite directions. All move with exaggerated walking steps with arms extended out to the sides when the leader is calling out his lines. When the chorus begins, the circles stop and each individual faces someone in the opposite circle. The two do a short dance pattern together (using 'ori tahiti dance movements). After the chorus finishes, all resume "walking" around in their individual circles.

Though the text of the songs is the most important element of this type of dance, it is sometimes difficult to understand because many stories incorporate old words with lost meanings, or are recited so quickly that it is difficult to understand the words. Sometimes, the rhythm of the syllables used and the sound they make have greater importance than the actual words.

Costumes for this style of dance are inspired by traditional Tahitian costume dress and are similar for those worn for pa'o'a.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Barrow, T. Art and Life in Polynesia. Charles & Tuttle Co., Rutland, VT. 1972.

- Gathersole, P., Kaeplpler, A.L., and Newton, D. The Art of the Pacific Islands. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 1979.

- Moulin, J.F. The Dance of Tahiti. Christian Glceizal, Paplette, Tahiti. 1979.

- O'Reilly. Dancing Tahiti. Nouvelles Editions, Latines Dossier 22, Paris.

'OTE'A BASIC DANCE STEPS

'OTE'A BASIC DANCE STEPS

by Merilyn Gentry and Nora Nuckles

- Kapa

- Step-push, same hip. Side-to-side movement, same hip as leg.

- Ohuri

- One direction only. Hip circle, accent on back half.

- 'Otu'i

- Any pattern of uneven Kapa.

- I'i

- Hand-held whisk (two).

DOCUMENT

- Tahiti, a country.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, October 1995.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.