|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Yaqui Deer Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

Americans are familiar with the Yaqui Deer Dancer through Amalia Hernandez' brilliant choreography for Ballet Folklorico de Mexico. A muscular young man wearing a loincloth, his head crowned with the head of a stag, is pursued by two hunters. The dancer's athletic and powerful performance transforms the dancer into the deer as he frantically flees his pursuers until he is eventually and dramatically slain. The deer's death throes are countered by the reverence shown him by the victorious hunters, for whom the deer's body and spirit mean life — a dramatic and spellbinding masterpiece.

Americans are familiar with the Yaqui Deer Dancer through Amalia Hernandez' brilliant choreography for Ballet Folklorico de Mexico. A muscular young man wearing a loincloth, his head crowned with the head of a stag, is pursued by two hunters. The dancer's athletic and powerful performance transforms the dancer into the deer as he frantically flees his pursuers until he is eventually and dramatically slain. The deer's death throes are countered by the reverence shown him by the victorious hunters, for whom the deer's body and spirit mean life — a dramatic and spellbinding masterpiece.

In reality, the deer dancer is only one of several characters who enact the Yaqui version of the Christian Easter, a colorful mix of Christian and pre-Christian storytelling. He is a remnant of ancient rituals in which he represented the deer upon which the people depended for food and shelter. In the Easter ceremony, he represents the forces of good against evil.

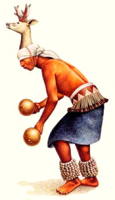

The deer dancer is indeed a muscular young man, bare to the waist, and wearing a black shawl wrapped skirt-like around the waist, belted with a wide leather belt, from which hang hundreds of tiny deer hoofs on short leather thongs. His ankles are wrapped with strings of cocoon rattles and he carries a large red gourd rattle in each hand. His head is covered to the eyes by a white cloth tied behind his head and surmounted by a real or imitation deer's head. The antlers are decorated with red ribbon forming a cross and representing flowers. His movements imitate the watchful movements of the deer and he virtually becomes the deer, the white scarf shielding his eyes and human features.

He dances in place with short, fast vibrations, turning and twisting as he listens and watches for the evil about him. The gourds are shaken, the waist twists and the legs vibrate, creating the dry rattle of deer hoofs and cocoons. His musicians play a flute, beat a gourd floating in a pan of water, and set the rhythm with a loud wood rasp.

The deer dancer dances next to the "pascola," an old man who acts as the official host. Though on the side of the church, he is a mischievous character, often interfering with and teasing the deer dancer. He wears a black wooden mask with white hair, sometimes on the side of his head, is bare to the waist with a blanket wrapped around his legs and belted similar to the deer dancer. His rattle is a wooden board with holes in which metal disks are mounted. His dance is similar to the deer dancer, except that the deer-like gestures are absent.

The church supporters include the "maestro," who directs the rituals, and a variety of flag bearers, singers, alter women, and angels.

The "Fariseos" is the society which represents those who persecuted Christ — therefore evil, through the roles of several different characters: the captain, who is "Pilate," "caballeros," and the "chapayekas."

The "chapayekas" are most visible, masked with hideous likenesses of evil spirits (politicians and hippies have been observed). Their upper body is artfully wrapped in a blanket and each carries a wooden dagger and sword, painted white with red and black designs, which are beaten together to create an ever-present harsh and evil rattle. A deer-hoof belt is also worn and effectively used to communicate. Each man carries a small crucifix in his mouth during his time as a chapayeka to protect him from the evil he portrays.

The caballeros, dressed in black, begin the ceremonies with the chapayekas, but abandon the Fariseos on Ash Wednesday for the church.

"Matachinis" are the society which protects the Virgin Mary and escort Her image in all processions. Generally they are young men and boys, many dressed as the Virgin. In a tight formation, their dance is a complex stamping rhythm, raising dust from the dry ground.

The whole Easter ceremony tells the story of ever-present evil and the need to defend against it, a story well-taken by the intended audience of children. It lasts all week from Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday in the plaza in front of the church. Yaqui churches are built with a large opening facing onto the plaza to accommodate the many processions which enter. On Saturday night before Palm Sunday, an all-night fiesta is held at the church with the matachinis and their musicians in attendance. Soft gentle music wafts through the plaza, blending with the fragrance of food from the community kitchen. The deer dancer and pascola are in their ramada to the side of the church, the pascola fulfilling his role as host and storyteller.

The chapayekas appear nearby, mimicking the dancers. Evil has arrived and the children shiver with real fear.

Palm Sunday rituals are a colorful introduction of the characters with much music, singing, and dancing. Each society or dancer has their own musicians and singers, each unique to itself. During the week several rituals occur, including processions visiting the Stations of the Cross, Chasing the Old Man (the Yaquis envision Christ as an old man), the Capture of the Nazarene, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection, all with prescribed ritual and ceremony performed in perfect solemnity.

The week climaxes on Easter Saturday with the "Gloria." The deer dancer, pascola, maestro, matachinis, and caballeros gather in front of the church. They are armed with an enormous mound of flowers with which to ward off the Fariseos who are preparing to attack. It is high drama, indeed, as the chapayekas attack again and again, repulsed in a shower of flowers thrown by the defenders as the deer dancer and pascola dance frantically in the fore front, musicians' drums and flutes urging them on.

Finally, the chapayekas break through the defenders and enter the church. Suddenly, it's over. With the entrance into the church, the chapayekas are "saved" and it is time to shed the identity of evil. With great ceremony, the chapayekas' masks and swords, along with props from other characters, are gathered in a pile in the plaza to be ceremoniously burned.

Members of the tribe are dedicated by their parents to the various societies as a form of gratitude for health or recovery from illness or any other event for which thanks are appropriate. Some are for life, while others may be for a certain period during the young person's life.

Yaqui society revolves around nearly 200 religious rituals each year, of which Easter is the most important. The tribe living in and around Tucson, Arizona have separated from the tribe in Mexico, who have never settled a long-standing war with Mexico. They are an integral part of Tucson society, though generally in the lower socioeconomic levels. Their Easter is a fascinating and honest example of dance as religious ritual, theater, and storytelling and can be observed to this day in the plaza in front of the church.

Visitors need to understand both the seriousness of the ceremony and the casual attitude toward any kind of schedule. Frequently the participants are delayed by their jobs and everyone patiently waits for them to arrive. Though the most visible and dramatic events take place on the Saturday and Sunday of Easter, Wednesday is a good time to arrive to see the preliminary events. Most take place at night (it's cold) and one must be patient.

REFERENCE

A Yaqui Easter, Muriel Thayer Painter. Published by University of Arizona Press.

DOCUMENT

- Richard Duree, an article.

Used with permission of the author.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.