|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

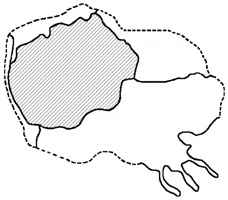

Macedonian Dances of Promahi

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

I first visited Promahi in the winter of 1964. I arrived in this northernmost, literally end of the road, mountain village just as a fierce snowstorm struck. Forcing me to hunker down for a longer stay than I had planned, it also freed up the villagers from work as usual and gave me the perfect opportunity to extend my research. I had no inkling of the wonderful dances that awaited me and the adventure in learning how to do them that was ahead.

I first visited Promahi in the winter of 1964. I arrived in this northernmost, literally end of the road, mountain village just as a fierce snowstorm struck. Forcing me to hunker down for a longer stay than I had planned, it also freed up the villagers from work as usual and gave me the perfect opportunity to extend my research. I had no inkling of the wonderful dances that awaited me and the adventure in learning how to do them that was ahead.

I had come from Athens, and before that, a year in the poorest rural areas of Yugoslavia and Bulgaria where the folklore was. We might sleep five in a bed but those people knew songs and dances. In those countries I almost had to fight to meet peasants. The Communist authorities wanted to show me new tractors and factories. When I said I was interested in folklore they took me to concerts. I've told that story elsewhere.

In Athens I stayed at the home of Nana (na-NA) Stefanaki. As it happened she came from a wealthy family. For her, this was the wherewithal to pursue folklore research, particularly to collect authentic costumes, her first love. She was a dance instructor, researcher, and patron for the women's lyceum of Athens, which was very keen on authentic village dancing. Several times a week I joined the men invited to rehearsals and practiced the basic repertoire.

Nana had visited Promahi several times. She arranged for me to go. Promahi, on the Yugoslav border, was a forbidden zone for tourists then. Greece was just coming out of a terrible civil war. The Army was afraid that people looking to travel in the north might be agitators. Nana through her political friends in high places arranged for all my travel papers. Finally I headed north to Macedonia, in a borrowed Volkswagen, with my trusty Uher tape recorder. The Army stopped me just south of Edessa. They cleared me for travel to the border villages but assigned a police guard to keep me from trouble. Recording songs in the Slavic language was strictly forbidden. It was inconceivable to them that I might want to record songs because I was a folklorist.

I was to stay with the village arhon (AR-khohn; the lead citizen of a village, often the most wealthy; the English word "monarch" has the same Greek root). Today his home is preserved as a museum to show a typical large house of that time, with kitchen, living rooms, bedrooms on an upper floor, and stalls for animals on the ground floor, the custom in this part of Macedonia. The upper floor has a chardak, a balcony or porch. I was born in Minnesota and knew cold winters, but my idea was that bedrooms should be heated. Not here. Beds were covered by what seemed a ton of thick blankets, flokati (in Greek) or yamboliya (in Slavic), made with five-inch strands of lamb's wool. Only in the kitchen a wood fire burned through the night for baba (grandma), who slept next to the stove. In the morning my challenge was to get up and dress in the freezing cold and then run to the kitchen as fast as possible where baba had put more wood on the fire and breakfast was being prepared.

On my first morning, after a few minutes of warming up next to the stove, I asked where I could wash and shave. My hosts pointed to the chardak outside, where a water basin was sitting on a table. I dashed out as snowflakes fell. The basin was under an inch of ice. What should I do? I quickly went back to explain that the water was covered with ice. I think it was one of the women who gave me that You Americans must be really dumb look and said "It's simple. Just break the ice and shave!" "But," I protested, "I am used to shaving with hot water!" Everyone began to laugh. Imagine, a country where men shave with hot and not cold water! But in keeping with Balkan rules of hospitality, the women of the house ran out and grabbed the basin and heated the water on the stove for me. Then one of the men piped up, "Would you like to sleep in the kitchen with baba too?" This brought another round of hearty laughter. My new friends were convinced Americans were a very soft and spoiled people with strange habits.

I was eager to start dancing but I was told it would take a few days for the local gajda (bagpipe) player to reach us on donkey-back because of all the new snow. We also couldn't get the local brass band together until the following Saturday.

Finally the gajda player arrived, resplendent in his kalpak (lamb's-wool hat) on a well-groomed donkey. He played solo. Oh, what incredible music. I managed to follow the steps after a few days if someone else was leading, but I could find absolutely no relation between the dances and the music. Without percussion instruments to help I couldn't hear the beat at all. Who were these people? Was it something in the water? Had I discovered new rhythms never before known to man?

Finally the gajda player arrived, resplendent in his kalpak (lamb's-wool hat) on a well-groomed donkey. He played solo. Oh, what incredible music. I managed to follow the steps after a few days if someone else was leading, but I could find absolutely no relation between the dances and the music. Without percussion instruments to help I couldn't hear the beat at all. Who were these people? Was it something in the water? Had I discovered new rhythms never before known to man?

Way too soon the gajda player returned to his village and I was forced to continued my studies to taped recordings made on my trusty Uher tape recorder. At first I started on the chardak where the ice water had been, outside, above the livestock – dressed in full winter garb. But as more villagers arrived to help teach me (as a letter from Nana had asked them to do), we were forced to go down to the more spacious courtyard below where we continued to go through these unusual and intriguing Macedonian dances from Promahi. When Saturday came and the band arrived I at last began to comprehend how the dances went to the rhythmic phrases and melodies. Melodies! What melodies? With the local combo of clarinet, trumpet, and trap-set drums the rhythm was clearer, but their harmony seemed to be from another planet. Gradually I understood. I recorded the band and practiced just about daily, during my stay and after I left the village for the next few months, alternating between the two: gajda and brass band. I was afraid I'd forget these dances for sure.

Back home I tried to teach the Promahi dances. I wondered if I myself had been transformed. There seemed to be only three or four people across the U.S. and Canada who could follow them. I gave workshops, appeared at festivals, and directed performing troupes, with good success in various folklore. If the moment felt right I would offer dances from Promahi. People couldn't tell what I was so enthusiastic about, and they couldn't do the dances. I heard reports of other travelers saying "No one in Greece dances like that." After a while video recording was a lot easier, and videos of Promahi got around. The yearly Folk Dance Festival of the West Coast Diocese of the Greek Orthodox Church in America began to take an interest in many folklore regions. I taught folk dance groups, and worked hard to give some of them Promahi dances. By now hundreds of dancers or more in America, France, and Germany have found how much fun these dances are.

I have been going through my library re-issuing music on Compact Discs. For these compact disks I have used modern electronic hardware and software, greatly improving the published sound quality. My CD FA-11 Edessa has music of Promahi and the nearby region, including my 1964 field recordings. I recommend it as the best I know. Here are the main dances:

Gajda (GUY-duh) in 2/4 rhythm is a local version of the common Sta Tria or Hassapiko found throughout Macedonia.

Hasapia (ha-sap-YA) is another local version. The Serbian dance tune Užičko kolo often appears.

Patrounino (pa-TROO-nee-no) is in 11/16; music 3+2+2+2+2, dance 3+4+4. "Patrouna" is a woman's name.

Sarakina (sa-ra-KEE-na) is an eleven-measure dance originally in 3/8, that is, 1+2; recently also in 7/8, that is 3+4. Also called Paidouskino (pie-DOOSH-kee-no); other dances in the family, farther north in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and in Bulgaria, are often in 5/8 or 5/16, that is, 2+3. Recently I dug up the words to the song, Sarakina moma (moma is young unmarried woman in Slavic). A popular 7/8 tune Raiko is named for a nearby mountain.

Stankino (STAN-kee-no) is in 11/8 (slow music) or 11/16 (fast music); music 2+2+3+2+2, dance 4+3+4. "Stanka" is a woman's name. Other local tunes are Molaevo (mo-LIE-eh-vo) from mullah, a Muslim clergyman, and Suleimanovo from a Muslim man's name. South of Aridea can be found other versions of this dance, that is, Bukite Razviat and Marina.

Tikfeškino (tik-FESH-kee-no) is in 2/4. Tikveš is a pumpkin, also a town in F.Y.R. Macedonia. Also called Krivoto (the crooked dance) or Koutsos (koo-TSOHS, limping; Greek).

Trite Pata (TREE-teh PA-ta) is in 7/4 (slow music) or 7/8 (fast music), that is, 3+2+2. Trite Pata means "three times" or "three steps". Also called Saflitsena (saf-LEE-tseh-na).

DOCUMENTS

- Dennis Boxell, an article.

- Greece, a country.

- Macedonia, a region.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.