|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Peoples of the North Caucasus

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

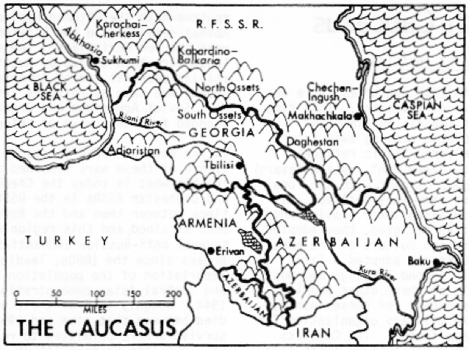

The Caucasus Mountains, which stretch for approximately 250 miles from the Black Sea in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east, and the fertile plains to their north have been the homelands of numerous ethnic groups.

Ethnically and linguistically speaking, this region is the most heterogeneous on Earth. The North Caucasus is so linguistically diverse that it was referred to by Arab geographers as "The Mountain of Languages." Within this relatively small region over fifty distinct languages are spoken in eight different language families. As well as being the homeland of the indigenous Causcasic peoples, the fertile grasslands of the North Caucasian foreland have attracted many nomadic peoples (Huns, Turko-Tartars, Iranians, and Mongols) and settled agriculturalists (Slavs, Greeks, and Armenians). Virtually all of these peoples left their mark on the ethnic and linguistic composition of this region.

|

The region also exhibits a varied religious pattern. Although the majority of the inhabitants of this region are Sunni Moslem, other religions are represented. The majority of the Abkhaz and the Ossetians are Eastern Orthodox, as are the local Russians, Ukrainians, and Greeks. The Armenians are Armeno-Gregorian Christians. There are Mountain (Daghestani) Jews, Kalmyk Buddhists, and the Shiite Moslem Azerbaidzhans in Daghestan.

The earliest known inhabitants of the North Caucasus were the Causcasic peoples, related to the ancestors of the Georgians. In the northwestern Caucasian plains lived the Circassians, now a small remnant of a once more numerous and powerful people. Related to them were the Abazgi (Apsua). As a result of invasions by the Iranian and Turkic peoples in the Middle Ages, a group of Abazgi crossed the Caucasus and settled on their southern slopes among the Mingrelians (in Georgia). Those who remained in the North Caucasus are called today Abaza (Abazinians), and those who resettled in Georgia are called Abkhaz. A last group of northwestern Caucasians were the Ubykh, who inhabited the Black Sea coast area. During the 16th to 18th centuries almost all of these people were converted to Islam by the Golden Horde (Nogai and Crimean Tartars) and the Ottoman Turks.

NOMADIC INVASIONS

Between the 5th and 13th centuries the North Caucasus served as a battleground between the local Causasic inhabitants and numerous invading nomadic groups. In the 5th century the plains of western and central North Caucasus were taken by the Huns, who had been driven out of Europe by the Germans. They (by that time called Bolgars) remained in this region until being defeated by the Khazars (a Turkic people who adopted the Judaic religion and formed a large empire) in the 7th century. These Bolgars then divided into three groups. One moved northward along the Volga where they established the Bolgar State of the Middle Volga (the Chuvash are the descendants of this group). Another group, under their leader Asperukh, invaded the Balkans and established the Bulgarian State. The last group fled into the mountains of the Caucasus, where they formed the ancestors of the contemporary Balkars.

The Iranian Alans moved into the North Caucasian foreland in the 6th century. After their defeat by the Tartar-Mongol hordes of Ghengis Khan in the 13th century, they were forced to take refuge in the central Caucasus where they became known as Osi (now called Ossetian). The lowlands were then taken by Kypchak Turkic peoples (most notably the Nogai) who destroyed the Khazar empire. The remaining Kahzars mixed with these Kypchaks, adopted the Islamic religion and went over to speaking a Kypchak dialect. Their descendants, now called Kumyks, live in the northeastern plains of the Caucasus region. All of these peoples adopted Islam with the conversion of the Golden Horde and the spread of the Kypchak Turkic languages between the 16th to 18th centuries.

The eastern North Caucasus region is linguistically the most diverse. Almost thirty different languages are spoken there. These peoples (with the exception of the Chechens and Ingush) are collectively known as Daghestanis. Islam was introduced to this area by the Arabs much earlier than to the west. It was adopted universally except by a group of Iranic Jews, moved into the far eastern North Caucasus in the 5th century by the Persians in an attempt to halt the movements of the Turkic invaders from the north. These Jews formed a military colony and some retain the Jewish religion to this day.

UNITY OF FOLK CULTURE

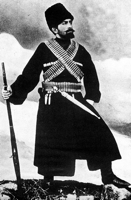

In spite of this great ethnic, religious, and linguistic complexity, the North Caucasians display an unusual unity in their folk culture. In contrast to the Balkans, where every regional and sub-regional group has it own costumes, music and dances, the North Caucasians maintain a common culture. The most striking example is the men's costume. Regardless of racial, ethnic, cultural, linguistic, or religious background, all male North Caucasians wear the same black sheepskin hat (papakh or kalpak), black waist coat (cherkeska), and soft black leather boots. This is the same costume worn by the Northern Georgians, the Svanetians, Mingrelians, and others who inhabit the southern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains. Women's costumes also display little variation (though more than those of the men). The groups also share many folk beliefs. For example, the Nart epics have been adopted by virtually all North Caucasians as their own.

These people also share a common way of life. Horsemanship was of particular importance. What is commonly called an "Arabian" stallion in the West (as the Europeans purchased them from Arabs) actually has its origin in the North Caucasus. Traditionally the eastern Circassians (the Kabards or Kabaratai) were the source of racing and show horses for the nobility of Turkey, Persia, and the Arab States. Marksmanship also was commonly important among all North Caucasian male cultures.

Dancing also formed a major part of North Caucasian male culture. The dance Lezginka (which is named for the Lezgin people of southern Daghestan) is done by all North Caucasian and Transcaucasian peoples. Many other dances also are common to all of these peoples.

So important were the three elements of horsemanship, marksmanship, and dancing in this region that a man's status was measured by them. One could not be considered a man (or have the right to marry) without showing proficiency in these activities. Men would get together at the Dahigit to display their abilities and compete with each other. To show their strength and agility they did dances in which they performed a variety of squat steps and danced on the knuckles of their toes.

LATER INVASIONS

Between the 16th and 19th centuries there was a different wave of invasions. This time it was by Slavs (mainly Russians and Ukrainians) who were running away from serfdom. These early Slavic refugees, called Cossack ("free man") by the Tartars, worked out a modus vivendi with the local Caucasians among whom they settled. Although they maintained their Slavic languages and Christian religion, they adopted the way of life and culture of the host peoples. The Cossacks adopted a Tartar dialect as their second language and most of the lifestyle of these other peoples, including the penchant for horsemanship, marksmanship, and military organization for which they became famous.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries there was a different wave of invasions. This time it was by Slavs (mainly Russians and Ukrainians) who were running away from serfdom. These early Slavic refugees, called Cossack ("free man") by the Tartars, worked out a modus vivendi with the local Caucasians among whom they settled. Although they maintained their Slavic languages and Christian religion, they adopted the way of life and culture of the host peoples. The Cossacks adopted a Tartar dialect as their second language and most of the lifestyle of these other peoples, including the penchant for horsemanship, marksmanship, and military organization for which they became famous.

The Cossacks also adopted the dance culture (with some modification) and the male costume of the North Caucasus. What is today associated with Ukrainian and Russian culture (in terms of the squatting dances of the men and the "Cossack" male costume) is actually North Caucasian. The event at which Cossacks displayed their horsemanship, marksmanship, and dance abilities was called the Dzhigitovka (a Slavic version of the Dzhigit).

In the early 19th century relations between the Cossacks and the local Moslem peoples broke down with the outbreak of hostilities between the Russians and the Ottoman Turks. These Russo-Turkish Wars were fought on three fronts: in the Balkans, in the Crimea, and in the Caucasus. The Cossacks were called upon as good Christians to aid the Russian government in its way against the infidel Moslems. The Caucasian Moslems received the same call from the Moslem Turks. The wars in the Caucasus region were particularly bloody. That and the movement of hundreds of thousands or Russian and Ukrainian peasants into the North Caucasus looking for free land after Russia freed its serfs in 1862 led to the decimation of the Moslem population. By 1864 it is estimated that nine-tenths of the Caucasian population was either killed or forced to flee. The vast majority of Circassians, Abaza, Abkhaz, Karachai, Balkars, Nogai, and Crimean Tartars who survived these devastating wars (and the entire surviving population among the Ubykh) emigrated southward to the Ottoman Empire. The only Abkahz remaining in the Russian Empire were the few Christians. The abandoned lands were then seized by Russian and Ukrainian peasants and by Armenians and Greeks who came as refugees from Turkey. Most Soviet Armenians and Greeks are descended from this wave of refugees.

In the eastern North Caucasus, the survivors of these wars remained and still inhabit what is today the Chechen-Ingush and Daghestan ASSRs in the USSR. Relations among them and the Russians have been strained, and this region experienced several anti-Russian and anti-Soviet outbreaks since the 1860s, leading to mass deportation of the population to Siberian and Central Asian concentration camps in 1944. Roughly half of their populations died between that time and 1958 when the survivors were permitted to return to the Caucasus (the Crimean Tartars, Moslem Armenians and Georgians, and Kurds have yet to return).

In spite of the facts that the surviving North Caucasians form only small remnant populations of once more numerous groups, and that most live as minority groups surrounded by a sea of Slavs, the North Caucasians remain among the least Russianized peoples in the entire Soviet Union. Considering the massive destruction of their populations in the 19th and 20th centuries, it is surprising that their cultures should survive at all. This is probably attributable to their own self image as morally, culturally, and in all ways (but sheer numbers) superior to the Slavs. It was not the CAUCASIANS who had to adopt the SLAVIC way of life in order to survive, but rather the other way around. In addition, the North Caucasians are acutely aware that the Slaves borrowed from them some of the most important aspects of their culture (the squatting dances, horsemanship, the North Caucasians male costume, many foods, etc.). Although small in number, the North Caucasian peoples have not only maintained their own cultures, but have strongly influenced those of their neighbors.

DOCUMENTS

- Ron Wixman, an article.

- Transcaucasia, a region.

Used with permission of the author.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, March 1983.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.