|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Pontic Music and Dance

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

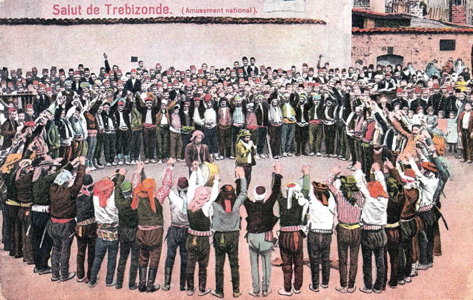

Once the easternmost of Greeks, dwelling on the southeast coast of the Black Sea ("sea" – pontos) in the general vicinity of Trebizond, Pontians were resettled into the mainland during the population exchanges of the mid-1920's, mostly in Macedonia. I met and danced with them in Naoussa and in villages near Florina and Thessaloniki during several of my research trips. In America we are greatly indebted to Nikos Savvidis, born near Kavala where his parents settled after leaving Pontos, who has inspired many with this folklore.

Once the easternmost of Greeks, dwelling on the southeast coast of the Black Sea ("sea" – pontos) in the general vicinity of Trebizond, Pontians were resettled into the mainland during the population exchanges of the mid-1920's, mostly in Macedonia. I met and danced with them in Naoussa and in villages near Florina and Thessaloniki during several of my research trips. In America we are greatly indebted to Nikos Savvidis, born near Kavala where his parents settled after leaving Pontos, who has inspired many with this folklore.

Pontic culture is alive today. You can hear its music not only in villages, often named after home towns with the prefix Nea (new), but in Athens, where there is a Pontic district, and even on commercial recordings. Those who speak modern Greek sometimes find the Pontic dialect difficult to follow, but linguists say it has strong remnants of ancient Greek. It has palatalized vowels and consonants, like ü in the German grün and chin the English "church;" there is no regular way of spelling these in modern Greek, but people who speak Pontic know to pronounce Serenitsa as shar-ya-nee-tsa, just as people who speak English know how to pronounce the words written as finger and singer. The dances catch on among Macedonian and Thracian neighbors, so that you can see other northern Greeks doing Tik and Dipat. Pontic musicians find a way to express themselves with modern instruments, but the lira and touloum are still much beloved.

The lira, also called kementse, is narrow and rectangular, played by a bow over three strings stopped by the fingers and tuned in fourths. The bow-hairs are wound with leather at the end the player holds, so that their tension can be changed by the fingers. The lira is held in the hand that stops the strings, or supported on the knee or thigh. During a fast-tempo dance, the player moves around freely with the dancers, even dancing a few steps with them. The lira is classically solo – except that the player keeps time by tapping his foot, maddening folklorists who want to record the music. This is the great Pontic instrument.

The lira, also called kementse, is narrow and rectangular, played by a bow over three strings stopped by the fingers and tuned in fourths. The bow-hairs are wound with leather at the end the player holds, so that their tension can be changed by the fingers. The lira is held in the hand that stops the strings, or supported on the knee or thigh. During a fast-tempo dance, the player moves around freely with the dancers, even dancing a few steps with them. The lira is classically solo – except that the player keeps time by tapping his foot, maddening folklorists who want to record the music. This is the great Pontic instrument.

The touloum, a bagpipe, is also a solo instrument (with the same exception). It has no drone, unlike the gaida played elsewhere in Macedonia and in Thrace. Unlike the lira, it traditionally is made by the player. Its chanter has two parallel pipes of equal length, flaring at the bottom, each with five holes. The player can cover the holes of both pipes with the first three fingers of one hand and the first two fingers of the other hand; for polyphonic harmony, he bends the fingers to cover the hole of one pipe and leave the other hole open.

The touloum, a bagpipe, is also a solo instrument (with the same exception). It has no drone, unlike the gaida played elsewhere in Macedonia and in Thrace. Unlike the lira, it traditionally is made by the player. Its chanter has two parallel pipes of equal length, flaring at the bottom, each with five holes. The player can cover the holes of both pipes with the first three fingers of one hand and the first two fingers of the other hand; for polyphonic harmony, he bends the fingers to cover the hole of one pipe and leave the other hole open.

The daouli is a two-headed drum, the diameter of the heads greater than the depth of the wooden frame. It is slung over the shoulder when the player stands, or rested on the knees or the floor when he sits. The main beats are struck by a thick stick shaped like a crook or a hammer, on one of the heads, which is thicker and tuned lower; the secondary beats are struck by a cane or switch on the other head. The size of the drum, devices for tuning, and the shape of the beaters all vary. Here we begin the instruments that are played in combination. Also, the daouli, laouto (lute), floyera (flute, end-blown or side-blown), and zurna (double-reed conical-bore woodwind), all characteristic of Pontic music, are played by others in Greece too.

To these folk instruments are now added violins, clarinets, accordions, even bouzoukis. The violin is sometimes a hybrid with a lira neck; modern violins are also used, tuned in fifths, or in fourths and fifths, although at the cost of playing in the parallel fourths typical of the lira. The bow is either a lira bow, or a modern bow with the frog discarded. In the traditional zurna-daouli band a clarinet often appears instead, usually with keys in C or B-flat. I have not heard Pontians use circular breathing, inhaling through the nose while blowing out air held in the cheeks, by which zurna players, and some clarinetists, achieve a continuous tone.

Pontic dances seem originally to have been in closed circles, a form unusual in Greece. The dancers hold hands, or sometimes shoulders. Fast music excites the characteristic tromakhton (trembling), seen in the upper body but actually rising all the way from the ground. The rhythms are often uneven, the beats in a measure not all of the same length, such as 5/16.

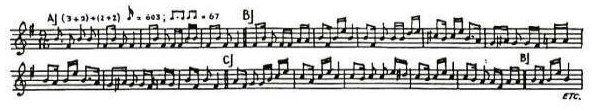

The most common dance is probably Tik (upright), in moderate, fast, or sometimes slow tempo. The rhythm is 9/16, 5/16, or 7/16, all of which feel like "slow-quick" to the dancer. Hands are at shoulder height with elbows bent, called "W position" by folklorists because a chain of dancers in this position looks like a line of W's. In slow tempo the flexing of the knees, and raising and lowering of the heels, makes the toes seem to stick to the ground. Tik has three triplets in place, one traveling diagonally forward (or toward the center of the circle) and right, and two steps straight back to place: five measures. In fast tempo the arms may be swung down twice while traveling to the right Here is a melody for Tik notated by Rickey Holden and Mary Vouras in 1965.

Tik is sometimes accompanied by song, especially in moderate or slow tempo. In 1974, Christian Ahrens found these poignant words.

O work abroad, many drink your poison,

They pour it into the heart with a glass;

They live with homesickness and want to return

To their wives, to their children.

Some work five years, others seven.

They struggle to earn much money.

One breaks his foot, the other loses his hand.

Working in a foreign land is a two-edged sword.

"Mother, where is my father?" the child asks,

My wife writes in a letter, it will cost me my life.

"Will you return home when it is too late?

Will you stay there nine or ten years more to earn more?

Stranger, your feet grow weary,

You do not recognize your children, they have grown up.

Your withered wife has half a soul left,

For her there is no life, she will pass on."

Omal Dipat (two-part) or Omal Trapezoundeikon (from Trebizond; omal means smooth or regular) is another common dance, slow or moderate tempo, often to singing. It is in 9/8 hands in W position; one measure forward and slightly right, one back, one in place. Here is a melody notated by Ahrens.

Kotsari (flashy) is a quick four-measure dance in 2/4 rhythm, done in one form or another by several ethnic groups throughout Anatolia: holding shoulders, three steps traveling right (actually a measure and a half), the rest in place. Kotsari is currently very 'hot' among American Greeks.

Omal Kerasoundeikon (from the town of Kerasous, now Geresun, Turkey) or Lakhana (cabbage, from an old song) is a quick dance in 9/16. It has only two measures: one traveling right, one in place, sometimes both or neither traveling. Hands are interlocked near the waist, or held in W position, or in high-energy moments raised overhead. I do not see Lakhana much in America but have had great joy in its subtle steps and changes of rhythm.

Serenitsa (from the town of Siran, southwest of Argiropolis) or Ikosi Ena (twenty-one) I am told is originally a women's dance. It is in 7/16 and quick tempo, two measures traveling right, two left, then dancers raise hands overhead and do four measures, in place, of the characteristic multiple-bouncing or trembling step. Letchina is similar: three measures left, two backing up as arms swing down twice and rise overhead, three in place.

Omal Kars (from the town of Kars, now in Turkey) is in 2/4 rhythm and moderate tempo, holding shoulders, one measure traveling right, two in place. Tas (outstretched, that is, the arm position) or Kiourtsias (Georgia) in 6/16 is a dance for couples face to face, a formation some Greeks know as antikristos; it holds a place in weddings of Pontians from the Caucasus.

Serra (name of a river, near Platana, now Akçaabat, Turkey), a men's dance in quick 7/16, is fierce, impressive, and difficult, the dancers executing combinations called by the leader. Performing troupes who master it have indeed something to be proud of. It is a good prelude for the mock duel to the death with knives, Maherta.

Other dances I have seen are Kots (ankle) in 2/4; Miteritsa (little mother) in 4/4, like a party game; Sari Kouz (blond girl) in 9/16; and Trigona (turtledove) in 9/16, which is done to a song. I am aware of perhaps a dozen others. Not all Pontic music is for dance, of course. There is music epi trapezios (at the table), which may include singing and music for weddings, such as Makrys Skopos (the long song) as the bride is led from her parents' house. I have by no means plumbed the depths of this vivid culture, but since I needed to compile these notes for a class I thought to share them with other fellow enthusiasts.

DOCUMENTS

- Dances of Pontos, an article.

- Dennis Boxell, an article.

- Greece, a country.

- Kots, a dance.

- Pontos, a region.

From Dennis Boxell's website.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.