|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Ukrainian Folk Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

In a historical context, the development of Ukrainian folk dance can be divided into three genres: Ritual, Social, and Thematic Dance. Of ancient origins, these dances were once a part of the calendar rituals for a people involved in agriculture and livestock breeding. These rituals were divided cycles that matched the work cycle of the agricultural year. They were used to welcome Spring, to observe the arrival of Summer (Kupalo cycle), to usher in the New Year, and as part of the harvest season (obzhynky). Because the people did not understand the forces of nature, "cults" arose that worshipped the "dark forces" of nature, each force having a "god" or "gods" associated with it. Examples are Svaroh, the god of the heavens and Svarozhych, the god of fire.

RITUAL DANCES

The Ritual Dances (Obrjadovi Tantsi) can be subdivided into four thematic groupings: those depicting work, those depicting socio-family relations, those abut love of nature, and those centered around patriotism.

No matter the theme, the main characteristic that separates the Ritual Dances from the other forms of dance genres is the fact that the text of the dance is its most important element and determines both individual movements and choreography. As they evolved over time, the dances became more intricate, graphically describing the content of accompanying songs. In most cases, the people dance to the accompaniment of their own singing.

The Vesnyanky, ritualistic song-dances to welcome Spring, fall into this category. Some of them include pantomime, as in the old rituals, where many of the phenomena of nature were personified. The "gods" or deified elements with their human-like needs and habits, were often depicted (that is, the god of light, Lada). They are usually done in a circle to symbolize the external form of the sun and the cycles of the seasons, with Spring coming as that part of the cycle that brings a reawakening of life.

With the coming of the Greco-Byzantine church, many of the pagan elements of these ritual dances were ousted. The more recent dances have a humorous and lyrical bent to them. A number of the Vesnyanky song-dances now have central themes of family relationships and of love, and the central figure is usually a girl.

Another group of Ritual song-dances can be seen during the Zelena Nadilya Festival, a celebration devoted to the appearance of Rusalky, the nymph spirits of drowned girls and unbaptized children. All these spirits are beautiful and love to sing and dance along the river banks and streams, their songs enticing young people to their deaths.

The main themes of the Kupalo Festival, held just before the harvest, glorify life and honor nature's life-giving powers, with romantic love a part of that theme. A straw dummy is one of the main elements of the festival. During the day, the boys of the area collect the materials and build the dummy while the girls collect flowers and braid them into wreaths for the dummy to wear. In the evening, the girls do circle dances around the dummy while the boys try to snatch the wreaths. After the dance, the girls throw the wreaths into the river. Superstition has it that whatever happens to the wreaths will determine the love life of the girls for the coming year. Meanwhile, the boys build bonfires. When the fires die down, the boys leap over the embers to rid themselves of evil and corrupt spirits. During the Kupalo, there also is the exchanging of gifts and the beginnings of courtship rituals.

Festivals to usher in the New Year are generally accompanied with many songs. These include the Kolyady (carols) sung from December 24 to January 1 (the winter solstice) by village people who go from house to house, glorifying the house and its master and wishing all a good harvest in the year to come. Usually, the New Year's Eve songs, the Schedrivky, are accompanied by a performance of Melanka (new year), done only by the village boys. The scenes of Melanka were originally meant to influence future harvests. One of the story lines tells of an old lady who betrays an old man. Death then comes along and kills her with a scythe. The old man then asks the mistress of the house (the house at which the actors are performing) for some money with which to buy the old lady some medicine. When she gives him the money, he goes to the doctor's house, gets the medicine, and returns to give it to the old lady. She revives and all is well. The Schedrivky have since evolved into expressions of general good will.

SOCIAL DANCES

The Social Dances (Pobutovi) have evolved alongside the Ritual Dances as an integral part of the cultural lif, and many of the basic steps evolved from those ritual dances. Examples include the prostly krok (ordinary step), the potriyniy prytup (triple stamp), and the prysyadka (squat step).

The themes tend to reflect the manners and customs of the people. Expressed through the basic choreographic structure of the dance, the themes also depict some of the character of the nation as a whole – love of freedom, heroism, courage, tenacity, ingenuity, humor, and resourcefulness. Social dances are generally done to musical accompaniment rather than to singing.

One of the better-known social dances is the Hopak (to jump). It began its evolution during the latter half of the 15th century, a time when increasing feudal exploitation caused numerous serfs and peasants to leave their villages to become Cossacks (free people). After a while, these people settled into the central areas of the Ukraine, near the Dnieper River. They were eventually overrun and forced to move again. Settling in the steppes regions bordering the Dnieper, they became very militaristic, going out on frequent raids to neighboring communities. On returning from these raids, the men would dance in the streets, improvising all the while. These dances have evolved, through time into the Hopak, a dance that reflects masculinity and strength, as well as grace, gaiety, and jubilation.

Another dance of this ilk is the Kozachok (Cossack). It is differentiated from the Hopak by a repetitive sequence of figures, based on traditional ornamental figures such as stars or chains, as against the improvisational nature of the Hopak. There are rapid transitions between figures, and the dance ends up very fast. The pace begins to slow then accelerates never going to a slower tempo again.

THEMATIC DANCES

Originating later than either the Ritual or the Social Dance forms, the Thematic Dances (Sinzhetni), are derived from the ritual song-dances and are considered an extension of them. Illustrative pantomime is used as the descriptive base, differentiated from the ritual song-dances in that the text is omitted here and only individual words or phrases are used to call changes in the dance figures. So, the content development here is more dependent on choreographic elements. The choreographies are similar to Social Dances in composition (lines, circles, and so on) and choreographic figures (stars, gates, weaves, etc.). Dance styling is heavily influenced by the geographic area in which the dance originated. The dances from the steppes regions tend to have broad, open movements while those of the mountain regions are quick and sharp

Thematic Dances depict work processes, that is, Shevtsya (shoemaker), and events of everyday life, folk heroism, and/or phenomena of nature. Some imitate bird and animal movements. Often, the dancers will use props in the dance as well as wear costumes.

By the time Thematic Dance was established, it had developed a "code" that reflected the social code of the village, so girls could not dance steps that would undermine their modesty (no high leg lifts or jumps), and boys were always polite and attentive to their partners.

DRAWINGS

Hutzul Formations

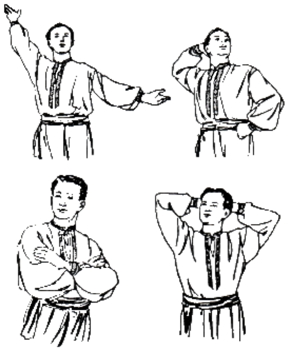

Hopak – Typical Positions

Hopak – Arm Positions for Spinning

Hopak – Arm Positions While Watching

Hopak – Arm Positions While Standing

Hopak – Squat Step and Follow-ups

Hopak – Leap and Pivot

Hopak – Coffee-grinder

REFERENCE

- Shatulsky, Myron. The Ukrainian Folk Dance. Kobzer Publishing Co., Ltd. Toronto, 1980.

DOCUMENTS

- Ukraine, a country.

- Ukrainian Dance and Music, an article.

- Ukrainian Dance Terms, an article.

Used with permission of an author.

A brief outline based on a text of the same title by Myron Shalutsky

Kobzar Publishing Company, Ltd., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1980

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, September 1988.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.