|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Dances of Slovakia

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

The dances of the Slovak people are as varied and as beautiful as the countryside in which they developed and as interesting as the people who inhabited this land. From the simplicity of village dances to the elaborate stage choreographies of present day amateur and professional ensembles, the movement mirrors the history and culture of a people who have clung tenaciously to their folk traditions and have succeeded in maintaining a strong Slovak identity despite centuries of subjugation. The dance, along with music and other folk traditions, lives today as a testimony of the Slovak spirit, and are indeed what Slovaks affectionately and somewhat reverently call the "pearls of Slovak culture."

HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

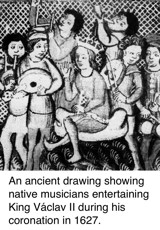

Although documentation is limited, it appears that Slovakian dance continually developed from the time of Feudalism. Archeological excavations testify to the existence of mimics, actors, musicians, and traveling troubadours (called igrici) as early as the Samos Empire in the 7th Century and the Great Moravian Empire in the 9th and 10th centuries. The igrici practiced their profession in the court of rulers or in the service of princes (joculatores nostri). They were best known as musicians but were dancers as well. From the 12th to 14th centuries, many records speak of the igrici; the instruments they played, the songs they sang, and various other activities.

Although documentation is limited, it appears that Slovakian dance continually developed from the time of Feudalism. Archeological excavations testify to the existence of mimics, actors, musicians, and traveling troubadours (called igrici) as early as the Samos Empire in the 7th Century and the Great Moravian Empire in the 9th and 10th centuries. The igrici practiced their profession in the court of rulers or in the service of princes (joculatores nostri). They were best known as musicians but were dancers as well. From the 12th to 14th centuries, many records speak of the igrici; the instruments they played, the songs they sang, and various other activities.

From the year 1114 until the 18th century, song and dance were mentioned primarily in the form of church prohibitions. Such activities were labeled as pagan rites and were prohibited in churches and cemeteries.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, evidence increases in the biographical records and diaries of nobility. Within instrumental collections of the nobility are found folk dancing songs under the names of Haducky, Odzemok, and Hungaresca. Concrete examples also exist of a variety of pastoral, ritual, and artisan's dances.

Dance notations such as the young miner's dance of Nová Bahá (1676) and iconographic memorials (such as, the Senica pulpit, 1692) also bear testimony to the dance. Dances such as the shovel dance, hat dance, candle dance, pawn dance, poppy seed dance, rooster dance, Slovakian dance, and heyduk are all mentioned in literature from this period by such writers as Daniel Speer, Ambrus Keezer, and Ladislav Bartholomeides. During the 18th and 19th centuries dances were described and mentioned frequently in various literary and local history works.

SLOVAK DANCE ROOTS AND OTHER INFLUENCING FACTORS

Although Slovak dance was shaped by many factors, its roots lie with the peasant and shepherd (Walach) cultures which inhabited the territory. The earliest inhabitants were peasants; agrarians who settled in villages and small towns in the lowlands along the Danube, Váh, and Hron Rivers. (There were no cities in Slovakia until the 12th century.) In these western, southern, and eastern regions, the peasant culture developed and the localization of Slovak culture had its beginning. The villagers were very isolated so there were great regional differences in the dance. Later, when orchestras began traveling from village to village, outside influences often crept into the dance.

The mountainous regions of Slovakia were even more sparsely inhabited and very underdeveloped economically. To remedy the situation, the nobility encouraged the shepherd's avocation by giving them various rights and privileges to settle in these regions. The granting of these advantages brought Walach shepherds into the country from Romania (13th and 15th centuries), from the Ukraine (15th and 16th centuries), and from the Polish side of the High Tatra Mountains (17th and 18th centuries). Every immigration wave brought new elements which were assimilated and transformed until finally in new cultural and social conditions, they formed a very unique music and dance style.

The conditions brought on by the Turkish wars in the 17th century also had an impact on Slovak folk culture. The social and economic drawbacks created by the wars brought misery to the country and meant sharper oppression for the serfs; the result was an increase in feudal warfare. One of the most spontaneous forms of protests against the ruling class was flight into the mountains where groups of robbers formed.

The conditions brought on by the Turkish wars in the 17th century also had an impact on Slovak folk culture. The social and economic drawbacks created by the wars brought misery to the country and meant sharper oppression for the serfs; the result was an increase in feudal warfare. One of the most spontaneous forms of protests against the ruling class was flight into the mountains where groups of robbers formed.

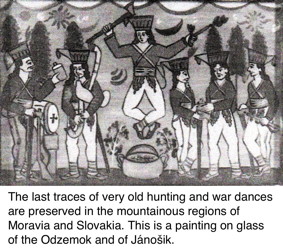

These robber elements strongly influenced the shepherd culture. Robber songs and dances came into being and became a rich part of the Slovak music and dance tradition. From this era evolved the legendary Slovak Robin Hood, Juraj Jánošik (1688-1733). Like many of the rural youth of his generation, Jánošik joined up with the anti-Hapsburg army of the Hungarian rebel Ferenc Rákóczi in 1703. After they were defeated in Trenčín in 1711, Jánošik entered the priesthood for a short time and then fled into the hills to form his own band of robbers. Jánošik was later betrayed by one of his own men, captured and hung in Liptovský Mikuláš. He became a great folk hero and many songs, tales, poems, novels, and plays have been written about his exploits. His belt and valaška (axe) supposedly gave him supernatural powers and this added excitement and mystery to his character. The impact of Jánošik upon the Slovak folk culture has been immense.

The Tartars and Turks both left a small mark on Slovak folk traditions, as did other ethnic groups such as the Germans who settled in Central Slovakia to work as miners, craftsmen, and artisans. For the most part their culture was assimilated by the Slovaks; nonetheless, their influence added to the rich variety of Slovak folk customs.

Obviously, there are many historical, geographic, climactic, and economic factors that influenced Slovak culture, but the peasant and shepherd cultures had the most profound effect on the formation of indigenous folk traditions. In some cases, it is easy to detect if a Slovak dance has either peasant or shepherd roots; however, many times the dance seems to be an interesting fusion of both or many different elements.

IDENTIFICATION AND EXAMINATION OF SLOVAK DANCE FORMS

A great deal of variety exists in Slovak folk dances in regard to function, technique, regional characteristics, and historical development. Finding a system that accurately identifies and explains the major dance types present in Slovak culture, and placing them in the proper chronology, is a task that eludes perfection. Two possible methods of analysis are 1) historical layers and 2) ethnographic regions.

It is possible to identify the main dance types by emulating the system used by dance choreologists from neighboring Hungary. The dances are grouped into different evolutionary stages by a systematic and scientific study analyzing such elements (to name a few) as function, formation, structural characteristics, and musical accompaniment. From such study, the dances are grouped into historical layers: 1) Dances of the Old Layer which date back to the medieval period, and 2) Dances of the New Layer which are a development of the last two centuries.

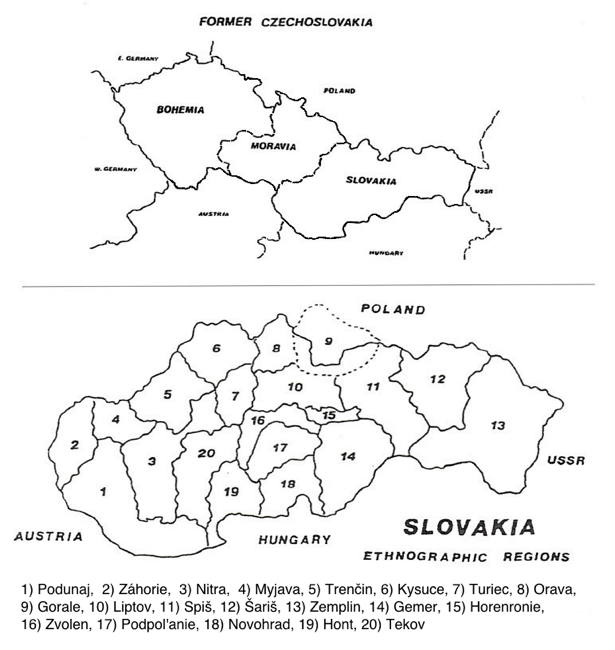

Another method used for classification is according to the various ethnographic regions which closely parallel the counties which were constituted in Slovak territory during the 10th through 15th centuries. These regions, along with various other factors, influenced the birth and development of the folk culture and its regional specifics (see map). Very unique dance dialects exist in each ethnographic region and each is a complex and comprehensive study in itself.

In this presentation, the writer will attempt to identify and explain the major Slovak dance types according to historical layers with references to ethnographic regions for added clarity and interest.

DANCES OF THE OLD LAYER

ARCHAIC DANCES WITH RITUALISTIC FUNCTIONS

We can ascertain that the early inhabitants of the area now covered by Slovakia danced; however, as with most cultures, the function of the dance was not for amusement. The dance, along with accompanying speeches and songs, were ritualistic in nature. Handicapped by a lack of scientific knowledge and completely at the mercy of their environment, people expressed their beliefs, needs fears, and joys through dance. They believed that dance possessed some magical power, and that through dance they could influence or manipulate the supernatural and natural. Their main concern was survival, and through dance they believed they could invoke rain, good hunting, health, fertility, and success in battle.

As time progressed, these old celebratory dances of the Slavs were passed on to future generations but with the original purposes behind the dances largely forgotten. Such surviving examples as the maypole or totemistic dances and dances that mimic combat, hark back to an earlier function of magic and worship which is now lost. Familiar dances in Slovakia with motifs portraying the bear or cock are remnants of ritualistic dances of an earlier era. It could be said that many of the dances existing today are direct descendants of early celebratory dances, but now these dances have social and artistic functions.

Archaic ritualistic dances are not considered a dance type per se, but are mentioned here for sake of chronology and historical background.

Chorovod

Dances in which men and women dance separately are older than pair (partner) dances and such is the case in Slovakia. The Chorovod, a collective girls' dance, is of great value because it is the most archaic dance form found in Slovakia today. Many of these dances have been lost and forgotten but examples still survive, especially in Eastern Slovakia where the peasant culture was strong. In Western Slovakia they have disappeared and in Central Slovakia they were never major dance form.(2) In Western Slovakia this dance form is often called Helička and in the East is is often called Hoja Ďunďa. Other common names include Omiliencei, Kadze Pavička, Letala, and Kačor. The names and forms vary according to region.

Dances in which men and women dance separately are older than pair (partner) dances and such is the case in Slovakia. The Chorovod, a collective girls' dance, is of great value because it is the most archaic dance form found in Slovakia today. Many of these dances have been lost and forgotten but examples still survive, especially in Eastern Slovakia where the peasant culture was strong. In Western Slovakia they have disappeared and in Central Slovakia they were never major dance form.(2) In Western Slovakia this dance form is often called Helička and in the East is is often called Hoja Ďunďa. Other common names include Omiliencei, Kadze Pavička, Letala, and Kačor. The names and forms vary according to region.

The dance is accompanied by the girls singing and the song is the dominant feature of the dance. The songs are very beautiful and are generally in 2/4 meter, although 3/4 meter dances also exist.

The dance consists of two parts. During the first part, four or five girls meet in the churchyard and in the second part they move through the village or to a meadow collecting other girls to join them. One girl acts as the leader and the others join hands in line forming a chain of dancers. Choreographically, the dance is very simple and consists of simple walking or running steps; however, it is the design that is interesting. The girls circle around a pole or fire, or weave the line into various shapes such as a circle, a "U" or "S" shape, or a curved form of zigzag.

Other common motifs consist of passing under various forms of arches made by one or more couples. Every village has its own shapes. In Šariš northeastern Slovakia, an interesting example exists whereby two rows of eight dancers move through the village making interesting designs before finally merging together in one line.

There is a springtime Chorovod in the Liptov northern Slovakia region where two rows of girls join arms across forming a bridge upon which one girl walks. The famous Lúčnica Ensemble has a beautiful stage choreography based on this Chorovod.

Many of these dances are associated with calendrical observances or seasons, such as: 1) the end of winter where girls weave through the village carrying a straw doll (Morena) which they finally burn or put in the stream to symbolize the death of winter and the birth of spring; 2) St. George's Day (April 24); 3) St. John's Day (June 24); and 4) Easter.

"Choosing" or "kissing" Chorovody are also found, such as the familiar pillow and kerchief dance in 3/4 time which has its counterparts in many other countries. The Gorale (an ethnic group living in the Tatra Mountains) have an interesting variant of this type in which a boy and girl are depicted as a cat and mouse.

This form of dance has declined greatly in Slovakia in recent years. Dancers generally did not accept them as dances because they occurred in places and at times when other dances were not done, and also because of their choreographic simplicity. Many of the chorovody have been absorbed into children's games which are often done in connection with school activities. More than forty such games have been identified and have been well preserved; perhaps because of their simplicity and the dramatic or pantomime elements that appeal to children.

Girls' Round Dances

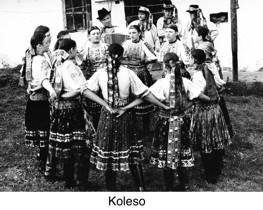

It is likely that the round (or circle) dances descended from the Chorovod because they are similar, both are danced by girls and women and the dancers singing forms the musical accompaniment. In the round dance only a circle is formed, whereas in the Chorovod various shapes are made. Hence, it is often called a ring, round circle, circle, or wheel dance. Both the Chorovod and round dance are among the oldest Slovak dances and are linked to the ceremonial round dances that can be traced across the whole of Europe. They are distinguished from them by more recent choreographic, musical, and functional peculiarities.

It is likely that the round (or circle) dances descended from the Chorovod because they are similar, both are danced by girls and women and the dancers singing forms the musical accompaniment. In the round dance only a circle is formed, whereas in the Chorovod various shapes are made. Hence, it is often called a ring, round circle, circle, or wheel dance. Both the Chorovod and round dance are among the oldest Slovak dances and are linked to the ceremonial round dances that can be traced across the whole of Europe. They are distinguished from them by more recent choreographic, musical, and functional peculiarities.

Round dances were often done during festive occasions when the orchestra took a break from playing, and even today this tradition continues. The songs, in 2/4 time and 4/4 time, are very rhythmical and beautiful.

Except for the western part of the country, circle dances are found throughout Slovakia. They may have existed in the west at one time but none are found there now. It is in Eastern Slovakia, especially in the regions of Zemlplín and Šariš, that the circle dances (Karicky) are the best perserved and the most highly developed. The style is very crystallized and the many motifs are extremely interesting and challenging. They differ greatly in style from the Middle Slovakian ring dances and from those of Northeast Hungary. This points to the special character and high degree of dance activity in East Slovakia.

The round dance is known by a variety of names, including Kolo, Kolesko, Kolesá, do Kolesá, Karička, Čuchom, and Körtánc. Kolesa and Karička are the more familiar names; Kolesa is the name used in Central Slovakia and Karička is used in Eastern Slovakia. The Hungarians call their round dance Karikázó.

Generally, the circle is formed by the dancers joining hands in a "front or back-basket hold" hands held with the second neighbors to either side. Also seen, but less common, is joining the hands down in a simple handhold, or "V" position hands held with immediate neighbors down at the sides, or moving the circle without joining hands.

The dance commonly consists of two parts. Part A is the slow, resting part; the motifs are quite simple and there is only moderate turning of the circle. In part B, the tempo increases, the steps become more difficult and the circle turns more rapidly. The dancers always maintain a perfect circle regardless of the tempo, difficulty of steps, or age of the participants.

Young Men's Dances

Old and variable forms to young men's or lad's dances are called Mládenécké Tance or Parobské Tance in Central and Eastern Slovakia. These all-inclusive terms generally refer to three types of men's dances: 1) Older Form of Lad's Dance, 2) Odzemok, and 3) Verbunk. Because the Verbunk is a "new" dance form, it is discussed separately under New Layer of Dances.

Older Forms of Lad's Dance

The counterpart of the girls' Chorovodny and round dances are the older form of lad's dances. They are somewhat analogous to the Hungarian Legényes because of their virtuosity and because both are an earlier dance form than the Verbunk.

The counterpart of the girls' Chorovodny and round dances are the older form of lad's dances. They are somewhat analogous to the Hungarian Legényes because of their virtuosity and because both are an earlier dance form than the Verbunk.

Many of these older dances originated and were danced as part of an initiation ceremony marking the transition from boyhood to manhood. Long after this ritualistic function ceased, the dances continued to exist for amusement and/or examination of ability. Musically, and in movement, the dances are related to the old couple turning dances and sometimes from the introduction to these dances.

More common is the group or solo form which varies greatly from region to region. Generally, the footwork is highly developed and the steps are technically and physically demanding. For example, in Záhorie west Slovakia the dance called Skoky is highly improvised and culminates in a competition to see who can jump the highest. In Horehronie central Slovakia the men perform very intricate and syncopated dupak (stamping) steps in a dance called Šórový. In Šariš, the men dance the famous Basistovska with motifs consisting of clicking the boots together, slapping the boots, and clapping the hands together in syncopated rhythms. Various names are given to the lad's dances and among the most common are Cifrovanie, Rozkazovačky, and Ćapéše.

Odzemok

Odzemok, considered by many to be the "national" or most typical dance of Slovakia, has been well preserved up to the present time. The physically strenuous and virtuoso movements of Odzemok, along with its martial elements, make it basically a man's dance that is very special, indeed.

Odzemok, considered by many to be the "national" or most typical dance of Slovakia, has been well preserved up to the present time. The physically strenuous and virtuoso movements of Odzemok, along with its martial elements, make it basically a man's dance that is very special, indeed.

Variants of the dance are known throughout the Carpathian region by various names and are often referred to as "weapon dances." Such dances were originally danced by soldiers, robbers, and shepherds, but later they were also danced by the nobility. Accounts of this dance form survive from the 16th century and by the 19th century information became more profuse. Still, in this century, its vigor is quite remarkable.

Odzemok is found everywhere in Slovakia but is richest in the central and northeast parts, especially in the High Tatra Mountains.

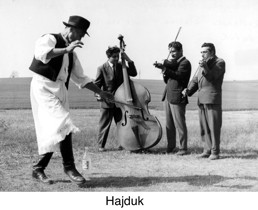

According to the Etnnografický Atlas Slovenska, fifty-seven different names for the dance have been identified. The most common name is Odzemok and it appears primarily in Middle Slovakia and part of West Slovakia. The second most common name is Hajduk and its variants, and this name is found especially in Spiš, Gemer, and Orava southern Slovakia. The name is tied to the weapon dances of the Hungarian nobles and especially the Heyduch soldiers of the 16th to 18th centuries.

According to the Etnnografický Atlas Slovenska, fifty-seven different names for the dance have been identified. The most common name is Odzemok and it appears primarily in Middle Slovakia and part of West Slovakia. The second most common name is Hajduk and its variants, and this name is found especially in Spiš, Gemer, and Orava southern Slovakia. The name is tied to the weapon dances of the Hungarian nobles and especially the Heyduch soldiers of the 16th to 18th centuries.

The third comprises a group of variants of the word Kozák found in the Northeast Slovakia and a scattering of other places. In East Slovakia, the name points to a relationship of the Ukrainian dance of the same name. Less widespread names come from various sources: 1) the beginning text of a song; 2) names associated with Jánošik or robber traditions (only in this century has it become known as the dance of the highwayman Jánošik); 3) shepherds and their work; and 4) implements used in the dance.

Odzemok is an improvised men's dance usually danced solo (especially in the past) and characterized by vigorous jumps and squats. Odzemok, roughly translated, means "from the earth" (or floor), and is descriptive of the dance movements. The dance is also danced in quartets, groups, and in rare instances by couples and women. In the group form, part A is the resting part and the dancers circle with simple, uniform steps. Part B becomes more lively and is characterized by agile jumps and squats.

Often the agility of the dancers is enhanced by the addition of implements. The most common of these props is the shepherd's valaška, an axe or hatchet that during an earlier time served as a weapon as well as a tool. In Central Slovakia, this is the older and more common implement. New props include sticks (found especially in East Slovakia), broom (found in Šariš), hats (found in West Slovakia), scythes (found in mountainous regions), and bottles. With the exception of the bottle and hat, all such props had their origin in the earlier weapon dances.

Often the agility of the dancers is enhanced by the addition of implements. The most common of these props is the shepherd's valaška, an axe or hatchet that during an earlier time served as a weapon as well as a tool. In Central Slovakia, this is the older and more common implement. New props include sticks (found especially in East Slovakia), broom (found in Šariš), hats (found in West Slovakia), scythes (found in mountainous regions), and bottles. With the exception of the bottle and hat, all such props had their origin in the earlier weapon dances.

While holding a specific prop, the dancer performs various actions, that is, swinging it beneath his feet or over his head, jumping over it, passing beneath his legs from one hand to another, and (in East Slovakia) twirling it between his fingers.

Odzemok is usually danced to violin and bagpipe music played in 2/4 time in moderate tempo. The most common song or melody is the well-known Po Valašský od Zeme and its numerous variants.

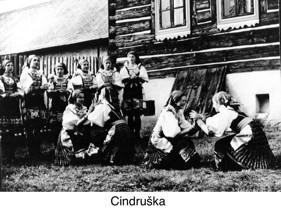

Only rarely in certain areas and under special circumstances do women participate in Ozdemok. Such dances take place chiefly where men's Odzemok dances are common and they have similar forms and names. In Orava northern Slovakia, among the Gorale, the women will join the dance. Also in the High Tatra Mountains is the very special dance called Cindruška or Cipovička (chicken). It is a type of party game done when girls and women gather together for an evening of spinning. The dance is performed as a solo, in pairs, or in a group, and has elements of squatting, jumping, and clapping.

Only rarely in certain areas and under special circumstances do women participate in Ozdemok. Such dances take place chiefly where men's Odzemok dances are common and they have similar forms and names. In Orava northern Slovakia, among the Gorale, the women will join the dance. Also in the High Tatra Mountains is the very special dance called Cindruška or Cipovička (chicken). It is a type of party game done when girls and women gather together for an evening of spinning. The dance is performed as a solo, in pairs, or in a group, and has elements of squatting, jumping, and clapping.

A rather unique form of Odzemok exists in Šariš and Spiš where it has a ceremonial function. At weddings in these places, the master of ceremony dances a solo form of Odzemok.

Since 1945, the Odzemok has continued to develop. This is due primarily to the the popularity of various village, amateur, and professional ensembles who have kept it alive, and in some instances have added their own variations to the dance.

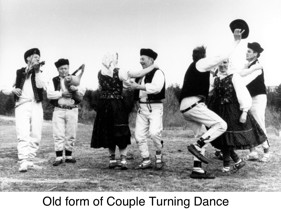

Older Form of Couple Turning Dances

Couple turning dances of the old style are historically linked to the Western European medieval and renaissance couple dances. Sporadic evidence of this dance genre exists from the 17th century and their occurrence culminated in the first half of the 18th century. At this time, improvised pair dances in 3/4 time were common in Slovakia. Because of the peculiarities of the dance and their frequency they were considered characteristic dances of the Slovak territory.

Couple turning dances of the old style are historically linked to the Western European medieval and renaissance couple dances. Sporadic evidence of this dance genre exists from the 17th century and their occurrence culminated in the first half of the 18th century. At this time, improvised pair dances in 3/4 time were common in Slovakia. Because of the peculiarities of the dance and their frequency they were considered characteristic dances of the Slovak territory.

Turning dances of this old style are spread throughout most parts of Slovakia with the greatest concentrations in West and Middle Slovakia. They did not appear in Southwest and South Slovakia, Kysuce northwestern Slovakia, and Turiec central Slovakia.

The dance has many regional differences but the motif common to all is turning as a couple in some form of closed dance position. The dance is highly improvised and the motifs are varied and rich. The male is dominant (as he is in society) and the female partner is only an accompaniment, submitting to the leadership of the male. In North-Central Slovakia, trio dances with one man and two women form a variant of this traditional couple dance.

It is characteristic of the dance to have a fixed structure consisting of four parts: 1) the man begins singing to tell (order) the musicians what melody to play; 2) the man dances solo; 3) the man invites the woman to dance and they turn as a pair; 4) man and woman separate and each dances individually, the man performing more virtuoso steps. This fixed sequence is not always present in every region and the order may vary slightly.

Dependent on the region, either bagpipes, violins, or a brass band provide the musical accompaniment for the dance, and the music is played in 2/4, 3/4, or 4/4 time in moderate to quick tempos. Moderate tempos appear to be the most common. In some areas, that is, Podpol'anie and Terchova southern Slovakia, both tempos exist and may change from moderate to quick during the course of the dance.

The dance has many names including: Sedliacka, Friška, Vrchovská, Krucena, Krutena, Skoč;nq, do Skoko, Starosvetská, Slovenčina, Šiková, Redovi, and Rovná. Sometimes the dance is incorrectly referred to as a Čardáš, a Hungarian dance which, during the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, spread and became domesticated also in the environment of non-Hungarian nationalities of former Hungary. It is likely this error occurred because of the fact both forms are couple turning dances and villagers therefore thought of them as the same dance; or they saw no need for making a distinction between the two forms. In some instances, elements from the old turning dances were adopted into the Čardáš resulting in a mixture of forms. Cases also exist of dancing the old style dances to new Čardáš music.

Recent research has identified 306 instances of the old style turning dances in Slovakia, 93 point to different dances.

DANCES OF THE NEW LAYER

Verbunk

The Verbunk had its origin in the 18th and 19th centuries during the Hungarian monarchy. In the second half of the 18th century, soldiers called verbunkoši recruited young men into the army by enticing them with music, dance, and other forms of revelry and their view of an exciting, carefree life. When recruiting ended in the first half of the 19th century, the dance continued to survive in the village repertoires, losing some of its military character and adapting itself to the local environment. It was especially strong in South Slovakia where the older types of men's dances such as the Odzemok and the old-style lad's dances had begun to decline.

Verbunks exist mainly in the southern part of West Slovakia, the northern part of West Slovakia near the Moravian border (Záhorie), and in East Slovakia in the Šariš and Zemplin regions where they are highly developed. Verbunks declined considerably between World Wars I and II. The most intensive occurrence of the dance in the first half of the 20th century was Northeast Slovakia, especially in Šariš.

The Verbunk is a man's solo dance or a group dance performed in a circle. It also exists as a couple dance (a later development) which is similar to the Čardáš and often identical to it. Such dances were usually a substitute for the slow Čardáš. The solo dance lends itself well to highly developed improvisation and both the solo and group forms are incredibly exciting and challenging. The dance has a strong, masculine quality and is usually characterized by various boot slapping (capas) motifs, as well as motifs involving clicking the boots together and clapping the hands in various syncopated rhythms. In the group form, usually simple, resting motifs alternate with the more difficult elements, and often it is danced according to commands given by leader. Such dances are a parody of military orders and have a humorous character. They exist in Šariš and Zemplin in East Slovakia where they are known mostly by the name Marhaňska. Other names for Verbunk include Solo Madar, o Suru, Vasvári, and Parobska Karička.

Violin music in 2/4 or 4/4 time in moderate tempo is the usual accompaniment for verbunks.

Čardáš

The Čardáš is a couple turning dance in the "new Hungarian style which, during the 19th and first part of the 20th centuries, spread throughout what is now Slovakia. It evolved from earlier couple dances and was influenced by Western European couple dances. The Čardáš music, an offspring of Verbunk music, helped in popularizing the dance. Although considered by many to be the national dance of Hungary, it is not recognized as the national dance of Slovakia.

The Čardáš is a couple turning dance in the "new Hungarian style which, during the 19th and first part of the 20th centuries, spread throughout what is now Slovakia. It evolved from earlier couple dances and was influenced by Western European couple dances. The Čardáš music, an offspring of Verbunk music, helped in popularizing the dance. Although considered by many to be the national dance of Hungary, it is not recognized as the national dance of Slovakia.

The Čardáš is occasionally danced in a circle, but it is predominately a couple dance. Partners assume a closed type of dance position and sometimes separate to demonstrate more virtuoso steps, especially by the men. The dance is improvisational with the man leading and making changes in motifs. In its early stages of development, the dance had three parts: slow, medium, and fast tempos. Later, only slow and fast tempos were common. The most characteristic motif in the slow part is the "double Čardáš step" called verbunk or lasunk. The fast part is called frisky and fast turning is the dominant motif. Couple turning dances of the old and new styles mostly crossed with each other in the quick part of the dance. In some areas, the čardáš is not much different, in terms of movement, from old couple dances; the characteristic features of the Čardáš being seen only in the music. This fusion with the old style contributed greatly to the development and widespread popularity of the Čardáš. Despite this mixture of styles, the Čardáš in most areas has a more recognizable and homogenous style than the old dance forms. Local and regional differences are less defined.

The most common nave given to the dance is Čardáš, and only in some places is it identified according to tempo or characteristic motifs.

Čardáš is found all over Slovakia, except for a few localities lacking a marked culture or dance tradition, and those where dances of the old style prevailed, such as in the Terchová microregion northern Slovakia.

Between the World Wars there was a gradual decline of the Čardáš, and in some places by the 1970s only the older generation were dancing it. However, recent research indicates that by 1980 it was still considered to be a well-known dance even though it was danced less frequently.

Modern Dances

The composition of the folk dance repertoire in Slovakia changed considerably during the last century. Because of various reasons, some dances vanished from the repertoire and new more fashionable dances were added. These newer dances came from urbanized Western Europe and had penetrated Slovakia by the second half of the 19th century by the way of Austria, Bavaria, Moravia, and Lower Hungary. Of these dances, the Waltz and Polka (also Čardáš) had the widest distribution; the Mazurka, Ländler, Steirer (Styrian), Schottische, Galopp, and Quadrilles were adopted in fewer areas and survived for shorter times.

Waltz

The origin of the Waltz (Volčik) is attributed to Austria and Bavaria and it arrived in Slovakia in the 19th century. Until 1918, it was known especially in West Slovakia, and between the wars and up until 1945 it spread to Middle and East Slovakia.(2) In the post-war period, its popularity declined. Nevertheless, it remains a basic part of the Slovak dance repertoire; considered by some to be a folk dance, by others a ballroom dance.

The Waltz can be characterized as a turning couple dance with three beats and usually the only motif. It has developed no definitive regional characteristics.

Mazúrka

The Mazúrka originated in Poland and came to Slovakia at the end of the 19th century. Its relatively uniform form, as preserved in Slovakia, shows that it did not come directly from the Polish folk environment, but via the fashionable European dance halls. In Slovakia, it was danced mostly in urban areas and had a shorter existence and danced in fewer places than the Waltz, Polka, or Čardáš.(2) It was popular mainly in West Slovakia, the adjacent parts of Middle Slovakia, and East Slovakia (Šariš).(2) The repertoire of brass bands indicates the Mazurka probably spread in connection with their activities.

The Mazurka was characterized in Slovakia by couples stepping and turning in three-beat motifs. Also present, but less frequent, were motifs executed in a fixed sequence. Other names for Mazúrka included Mazul'ka and Mazu'la.

In the first half of the 20th century the Mazúrka gradually died out and is preserved today in the reprertoires of various folk ensembles.(2)

Polka

The Polka arrived in Slovakia mainly in the second half of the 19th century, and, in contrast to the Waltz, had Slavic and above all, Czech origins. Like the older, indigenous dances it also had the more familiar 2/4 meter.

Slovakian Polkas appeared in several forms: 1) couple turning dances with one or two motifs; 2) multi-motif improvisational dances; 3) dance games; and 4) dances with motifs firmly bound to the musical phrase (that is, part A – simple Polka turn; part B – bowing, clapping, changing partners, or some such motif). Familiar names of dances from the four groups include Hrozena, Konena, and Cerjana. Some of the dances from the fourth group form parts of Quadrilles.

Like the Waltz, the Polka spread in the first half of the 20th century, beginning in the western part and spreading eastward. Between the World Wars, it reached the mountainous parts of Middle Slovakia so it was known throughout all of the country. It was transmitted mainly by soldiers and by the rural population. In Šariš in Northeast Slovakia, the Polka is very special with its quick tempo and intricate footwork (such as, Šarišská Polka).

The number of forms and the variety of names given to the Polka attest to its popularity. At least thirty-two names with numerous variants have been identified.(2) Some of these names are Židovská (Jewish), Krajcpolka (polka), Kováčsa (blacksmith), Čerjana/Cenc (changing partners), Strašiak (scarecrow), Tapkaná (clapping), Špacirpolka (walking), Ševcovská (shoemaker), Hopspolka (hop), Ceperka (stamping), na Šest (six), Skákaná (jumping), Trašena (shaking), Trcipolka (hip swing), Krútená Polka (turning), Rovná (straight), and Šlapák (stepping).

Ländler, Steirer, Schottische, Galopp, and Quadrille

These dances are strange in the Slovakian folk dance repertoire, being mostly rooted in a foreign folklore milieu. They were danced with various adaptations in European towns at the end of the 18th and 19th centuries, reaching Slovaks mostly by way of dancing masters who taught in the urban dance halls. During the 19th century they adopted a local character

The original Austrian-Bavarian 3/4 time Ländler is a related predecessor to the Waltz. It was danced mainly in the area around Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia (West Slovakia), and sporadically elsewhere.(2)

Another 3/4 time dance called Steirer (Styrian/Štajer), also of Austrian origin, was danced in Northeast Spiš in an area colonized by Germans, and came to Slovakia earlier than the flood of other modern dances.

The Schottische (Šotyš), of Scottish origin, is in 2/4 time with one melody and a fixed sequence of dance motifs. It is found in West Slovakia and sporadically in East Slovakia, especially in Spiš.

The Galopp, a couple dance of French origin characterized by sliding (chasse) steps was danced before 1989 in the area around Bratislava.(2)

The Quadrilles (Štvorylka), also of French origin, are a colorful mixture of various, often hard to identify fragments of ballroom dances. They are danced by three or four couples executing various quadratic patterns. Part of the Quadrille composition, called by the French name pas de quarte has remained in Slovakia as in an independent dance with a fixed form and local names, appearing most often in South Slovakia.

A relative of the Quadrille, but of a more recent form, is the Beseda (Czech and Slovak) dating from 1863 to 1926. The Besedy were taught and danced mainly between World War I and II and were kept more within the school performances in the environment of foreign Slovaks in Hungary than at home.

The Quadrille forms gradually died out in the first half of the 20th century. Distortion of terminology, the frequently uncertain dance forms, and the low degree of continuity with the dance tradition all contributed to the confusion and impurity of this dance form.

Various kinds and names of Quadrilles include: Štvorylka (Križák, štvorka), Padegatta (Paligátor, Barigator), Beseda, Francianéďés, and JapanČardáš.

Choosing Dances

Choosing or kissing dances are game-like dances in which a boy or girl carrying some prop such as a pillow, broom, or mirror chooses a partner from the circle of dancers. The first part of the dance is done to slow music and with great dramatics a partner is chosen. This is followed by a kiss or embrace indicating acceptance. The second part has a faster music and the couple does a form of turning dance, usually a Polka or, more rarely, a Waltz. The dance repeats with the chosen dancer becoming the next one to choose partner. Such kissing dances were popular urban dances in 20th century Europe; although evidence indicates an earlier origin.

The dance names are often tied to an action in the dance, such as kissing or to the props being used (such as, pillow, broom, handkerchief, and kerchief). Common names for such dances include: Ručnikovi (handkerchief); Šatkovi (kerchief); Hantuškovi/Chustkovi, Kendöstánc (scarf); Tichltánc, Vankúšovi, Vánoštánc (pillow); Zrkadlovi (mirror); Bozkávací (kissing); and Čóktánc (Hungarian).

Choosing dances were done mainly in West and Middle Slovakia and died out in the first half of the 20th century.

OCCASIONS FOR DANCE

For the most part, occasions for dance correspond to various familial and calendrical observances. Such events are marked by many specific customs and songs, and in many instances, by dances.

Births, weddings, and deaths are familial events which may include dancing. Today, rarely is dancing found at ceremonies of birth and death, although Chorovody were once danced at both occasions. In the 17th and 19th centuries, evidence exists of funeral dances; unfortunately, most of these dances have now been lost. Weddings provide the greatest opportunity for dance and include such forms as ceremonial dances (Chorovod), dance games, and dances from the local repertoire. The most common dances are: 1) the dance with the bride after the "capping" (Vceplenyu – putting on the bonnet symbolic of a married woman); 2) a dance in which the most distinguished guests take turns dancing with the bride; couple turning dances, 4) girls' round dances; and 5) Waltzes and Polkas. The names of the dances usually relate to the bride or to such symbolic ornaments as the wedding wreath (venček) or bonnet. Common names are: Mladuchin, Nevestin (bride); Brautski and variants (bride); Brautanc (German word, bride's dance); MeňasoŇltánc, Meňešketánc (Hungarian dialect); Redovi, Rajdovij, and variants (turning); and Rosa (dew).

Within the calendrical observances, Shrovetide provides the greatest occasion for dance. Shrovetide corresponds to our Mardi Gras or carnival and occurs 3 to 4 days before Ash Wednesday. Research indicates that Shrovetide dances were still a living tradition in the 1980s, especially in West Slovakia.

The most common dance of this genre are men's dances preformed with sticks and often called sabre dances. They are characterized by a chain-like linking of the dancers with sabres (often only of wood) or with sticks and rods. Such dances are very widespread in Slovakia and in South Moravia. Interestingly, they are absent in Eastern Europe, which points to a Western European origin. In Northwest Slovakia, these dances are called pod Sabre; in Middle Slovakia they are called Fašiangový Tanec or Tanec pod Paličky, Koleda, and Preskakovačka. Sometimes they have no name. In the southern part of Middle Slovakia, this chain dance does not exist, and they dance with clogs, bear masks, and around a spit or fire. Also, characteristic are couple turning dances adapted to the Shrovetide tradition, that is, na Kanope and Na l'an in which the jumps and lifting of the female partners are meant to ensure a good harvest.

In areas where specific Shrovetide dances no longer exist, couple turning dances and other couple dances from the local repertoire are danced.

Other calendrical observances that include dance are: 1) harvest; 2) winter spinning gatherings; 3) Christmas (reenactment of ancient plays called Bethlemci and Odzemok is danced; 4) Easter; 5) spring (the Morena ritual symbolizing the death of winter and the birth of spring and Chorovod is danced; 6) New Years (young men carrying a star, dance Hajduk with Valašaka and Bunkoši; and 7) religious observances such as Sundays after mass and Saint's Days (especially St. John's Day on June 24 and St. George's Day on April 24). In the past, other occasions for dance included the times when various artisans visited the village, when shepherd's returned from the salaš (sheep farm), and when wolves, which played on the sheep, were captured or killed.(3)

Some of he calendrical observances have declined or vanished over the years and are now perserved only within the repertoires of various folk ensembles.

OTHER CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DANCE

In generations past, dance events often reflected the economic status of its participants. For example, those who requested the orchestra to play various tunes were obligated to tip the musicians and were therefore assumed to be the wealthier members of the society. It was also customary for the daughters of the more wealthy villagers to stand near the front of the hall and they were the first to be asked to dance.

Generally, it was the responsibility of the young men of the village to hire the musicians for dance gatherings, and the musicians were paid with such things as grain, eggs, bacon, textiles, and other goods. Only for big and important events were musicians paid with money.

When musicians took a break from playing, the girls would dance round dances and the men would sometimes have various competitions, such as seeing who could jump the highest.

The men played a dominant role in the dance and only after World War I was it considered proper for girls to ask boys to dance.

It was characteristic to assume that a couple would soon be engaged if they danced together several times in one evening. Also, it was not uncommon for fights to break out between young men vying for the attention of the same girl. As the years passed, dances ended at very late hours and a competition of sorts existed between the musicians and dancers to see who could last the longest.

Curious superstitions also existed in regard to the dance. Girls would wear various protective herbs which they believed would enable them to continue dancing even when they were very old. It was said that anyone who danced during Lent would have his legs sticking out of the grave when he died.

ETHNOGRAPHIC REGIONS

One reason the study of Slovak dance is so challenging and interesting is because of the ethnographic regions, each possessing its own distinctive characteristics and style. Twenty such regions have been identified; a number considerably higher than that found in most other European countries. The regions are: 1) Podunaj, 2) Záhorie, 3) Nitra, 4) Myjava, 5) Trenčín, 6) Kysuce, 7) Turiec, 8) Orava, 9) Gorale, 10) Liptov, 11) Spiš, 12) Šariš, 13) Zemplin, 14) Gemer, 15) Horehronie, 16) Zvolen, 17) Podpol'anie, 18) Novohrad, 19) Hont, and 20) Tekov (see map).

These ethnographic regions were shaped many hundreds of years ago when rivers, mountains, or thick forests defined the boundaries between the different tribes; isolating them and limiting communication. As a result, individual cultural traits developed in all ways of life from language to architecture, from work habits to dance. These cultural clusters formed the basis for the various ethnographic regions so defined.

A monograph would be necessary to adequately discuss each region; therefore, only brief illustrations follow, except for the Gorale Region which has very unique characteristics.

Formations, steps, motifs, and style are some of the characteristics that contribute to regional variance and countless nuances are found even within one region from village to village. For example, in Podpol'anie, men dance only with their legs. Im Myjava, the woman is lifted and tossed, but in other regions such tossing motifs are absent. In Zemplin, only upbeat ridas pivots or buzz steps are done; in Šariš only downbeat ridas; on the border between Zemplin they turn in both directions. The round dances in Zemplin are danced with the bodies turned slightly in the circle; in Šariš the bodies face center. In the village of Pozdišovce in Zemplin, the Karička steps are rich and dominant; in the adjacent village of Parchovany the formations are rich. Such illustrations give some insight into the complexity, endless variety and subtle differences that contribute to the richness of Slovak dance.

Gorale Region

The Gorale Region, located in the High Tatra Mountains, is geographically situated in both Slovakia and Poland. Because of the mountainous isolation of this region, the dance and other folk traditions have been maintained in an incredibly pure form. The people are a shepherd culture and presumably their origins are linked to the nomadic Wallachian shepherds who wandered from the Balkans during the 15th to 16th centuries. Speculation also exists that their roots lie with tribes from the Caucasus; a theory reinforced because of certain similarities in dance style and more specifically the motifs emulating the stalking and protective movements of the "eagle." These unique people say they are neither Slovak nor Polish, and their distinctive dialect lends credence to this because few Slovaks or Poles are able to understand them with any proficiency. Their work habits, traditional dress, music, dance, and other customs differ greatly from those of Slovaks and Poles. They have a reputation of being adventurous and years ago they were known as being good horse smugglers. In fact a successful smuggle always culminated in a big village celebration with much music and dance.

The Gorale Region, located in the High Tatra Mountains, is geographically situated in both Slovakia and Poland. Because of the mountainous isolation of this region, the dance and other folk traditions have been maintained in an incredibly pure form. The people are a shepherd culture and presumably their origins are linked to the nomadic Wallachian shepherds who wandered from the Balkans during the 15th to 16th centuries. Speculation also exists that their roots lie with tribes from the Caucasus; a theory reinforced because of certain similarities in dance style and more specifically the motifs emulating the stalking and protective movements of the "eagle." These unique people say they are neither Slovak nor Polish, and their distinctive dialect lends credence to this because few Slovaks or Poles are able to understand them with any proficiency. Their work habits, traditional dress, music, dance, and other customs differ greatly from those of Slovaks and Poles. They have a reputation of being adventurous and years ago they were known as being good horse smugglers. In fact a successful smuggle always culminated in a big village celebration with much music and dance.

The characteristics of the dance are many and very unique. They dance on the balls of their feet with the body bent forward; characteristics attributed to their everyday habits of walking up mountains. For the most part, men and women dance separate from one another. The male takes the dominant role, vying with his peers to impress the female with his lightning-quick footwork and jumps in the air.

The female plays a more passive, demure role, performing small quick steps around her partner; turning and spinning at his command. In dance and in life, the woman is modest and passive; contrariwise, the man is dominant although (interestingly) he extends her great courtesy in the dance.

The main dance types in this region are couple dances and a men's dance, Zbójnicky, a fast, fiery dance that requires tremendous muscular agility with its many squats and jumps. It is danced with a valaška (axe) or a bunkoš (a stick with rattles on it to ward off bears and wolves preying on the sheep). With such an implement the dancer performs various movements as described earlier in the Odzemok.

The couple dances follow a very fixed order. First, a male dancer wishing to choose a partner, approaches the musician and sings a melody to which he desires to dance. Often, he improvises his own words to the traditional tune and makes them as funny and as topical as he can. The musicians pick up his cue and begin to play. A friend of the dancer approaches the girl that the dancer wishes to dance with and brings her out to the center of the floor. She follows him alone or will come out with two other girls at her side. The friend will dance with the girl a few moments before turning her over to the man that requested the dance. The dancing couple takes the center of the floor while the others congregate behind the man, who jumps in the air, stamps three times, and takes the girl in closed position to turn as a couple. At the end, the dancer takes off his hat and bows gallantly to his partner.

The couple dances follow a very fixed order. First, a male dancer wishing to choose a partner, approaches the musician and sings a melody to which he desires to dance. Often, he improvises his own words to the traditional tune and makes them as funny and as topical as he can. The musicians pick up his cue and begin to play. A friend of the dancer approaches the girl that the dancer wishes to dance with and brings her out to the center of the floor. She follows him alone or will come out with two other girls at her side. The friend will dance with the girl a few moments before turning her over to the man that requested the dance. The dancing couple takes the center of the floor while the others congregate behind the man, who jumps in the air, stamps three times, and takes the girl in closed position to turn as a couple. At the end, the dancer takes off his hat and bows gallantly to his partner.

The couple dances are in 2/4 time and the tempo of the songs which intersperse the dance is slower than that of the dance itself.

The couple dance exists not as a single dance but as a series of short dances that are done in a fixed sequence. The characteristic form and style remain constant but there is great individual improvisation. The melodies are short because the dance is vigorous and there are many melodies for the various dances. The order of dances may vary slightly but a typical sequence includes: 1) Osvodny (a simple walking or marching dance); 2) Krešany (a virtuoso dance with motifs consisting of striking the feet together); 3) Dubašiki (a dance with motifs consisting of low jumps and striking the feet together in the air); 4) Večna (called the eternal dance because it goes on and on – the tempo changes but not the motifs); and 5) Želona (the last dance).

Other common dances include Košiček (this means basket and is danced during the winter and on special occasions, especially at weddings), Skokačky (jumping dance), and Goralský Polka.

Repertoires vary somewhat from village to village.

SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH, DOCUMENTATION, AND AVAILABLE LITERATURE

Like most other Eastern and Central European nations, Slovakia had a rather late beginning in the collection, research, documentation, and publication of its folk traditions. It wasn't until the first half of the 19th century that any work was done. At that time, P. J. Šarfÿrik and J. Kollár made a systematic collection of songs, some of which concerned dance. B. Tabica, P. Dobšinsky, and P. Sucháň were other pioneers who made similar collections of melodies with dance songs included.(1)

A more systematic and better organized work began to be done only after 1918 when two institutions came into being: The State Institute for Slovak Songs and Matica Slovenská. Again, the primary emphasis was on music and from 1924 folklorist K. Plicka, J. Kresánek, and J. Valašt'an-Dolinsky made very valuable collections of melodies and song texts. It wasn't until the 1940s that the foundation of scientifically oriented ethnomusicology began to be laid, fundamental problems defined, and new attitudes and methods of work adopted.(1)

In 1951, the State Institute for Folk Songs was integrated, as a musical folklore department, into the Institute of Musical Science of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava. With the establishment of the ethnomusicology section, attention was also given to the scientific study of music and dance. The Academy archives now contain musical manuscripts, song texts, and audio recordings of songs and instrumental music. In addition, in the film archive are more than 350 field recordings of traditional dances recorded on more than 100 films (with synchronized sound track). Matica Slovenská also hosts a valuable archive of musical folklore.

In recent years, interest in field work has increased and ethnographers and choreographers have scoured the countryside searching for original dance for scientific purposes or as basis for new choreographies.

Ethnochoreologists St. Toth, Stanislav Dúžek and Cyril Zálešák have made invaluable scientific contributions, and recently Dúžek and Zálešák cooperated in the research and production fo the dance atlas included in the monumental work alled the Ethnografický Atlas of Slovenska.

Within the Academy of Sciences, a dance notation system has been developed and comparative studies with other European systems have been made.

Except for the works of Cyril Zálešák, Mária Mázarová, and Štefan Nosál', very few books on Slovak dance have been written. Adding to this misfortune, none of the books cited (including the Ethnografický Atlas of Slovenska) have been translated into English.

FOLKLORE GROUPS AND FESTIVALS

In the contemporary sense of the word, folklore groups are voluntary organizations that consciously preserve and perform folk songs, music, and dance. The conception of such groups took place within the so-called "folklore movement," a movement reflecting the growth of national awareness and ethnic-cultural identity. Its beginnings tie in with the formation of the amateur theaters in the last century. The first dance performance ever recorded was in 1615 when a group from Orava performed in Wittenburg. Chronicles indicate that performances by various other groups followed in the years 1850 to 1940.2

After 1945, the movement reached a high stage of development, and this was due to several factors. A revival in national awareness occurred and many events were organized highlighting this theme. Such events necessitated and inspired the formation of folklore groups. In addition, the Communist government looked favorably upon folklore and provisions were made for adequate funding. Lastly, young people's interest increased because such groups offered them the possibility of traveling to the West, a privilege otherwise denied under the Communist regime.

In the present framework of folklore groups, there are two professional ensembles S'LUK (Slovenskক Ludový Umlecký Kolekeiv) and PULŠ (Poduklianský Ukrajinsky Luový) and three semi-professionsl ansembles Lúčnica, Ifjú Szivek (Hungarian) and VUS (a soldier's ensemble).

Folklore groups operate within the framework of the Artistic Amateur Activity (ZUK) and approximately 13,000 groups of amateur artists comprise this organization. The Ethnografický Atlas Slovenska estimates that folklore groups comprise about a third of this total or 4,2500 groups. According to Dr. Stanislav Dúžek, this figure is too high and information secured from Narodne Osvetove Centrum (NOC) (called Osvetovy Ustav before November 1989), indicates that perhaps a more accurate count would be somewhere between 1,200 to 1,300. The number of groups fluctuates from year to year. Presently, NOC has information on 386 children's groups, 338 village groups, and 1,200 amateur groups. Regardless of exact statistics, the level of participation is very high; testimony once again to the love and value of folklore.

Three types of groups identified differ on their expression of folk art. The village groups focus on singing, reenactment of local customs, and traditional dances done with minimal stage choreography. Contrariwise, the ensembles (which are organized by Work Clubs and Culture Houses of the Revolutionary Trade Union Movement and by schools) focus on stylized folk dance with great attention to stage choreography. The children's ensembles present customs, children's games, and game-like dances.

In 1949, Matica Slovenská organized the first training schools for the leaders of the existing ensembles of the Czechoslovakian Youth Group (CMS), the Standard Farming Cooperative (JRD), and the Revolutionary Trade Union Movement (ROH). Since 1953, this function has been taken over by by the NOC. Teachers and choregraphers are well-trained in Slovakia, and for some of them directing an ensemble is a full-time position. Competitions are also held each year for choreographers to showcase their newly-created choreographies.

The rapid development of the folklore movement since 1948 necessitated the regular mounting of competitions, performances and folklore festivals. Village folklore groups hold their all-Slovakian competitions in Žilina northwest Slovakia and the children's ensembles in Prešov eastern Slovakia. The ensembles of youth and adults meet in various places for competitions and performances but the major events are the folklore festivals.

The major festivals are: 1) Myjava (West Slovakian Folklore); 2) Detva (Folklórne Slávnostic pod Pol'anou); 3) Košice (Festival of International Friendship); 4) Výlchodná (all-Slovakian); 5) Banská Bystrica, Brezno and Helpa (Folk Festival of Upper Hron); 6) Zvolen (Akademický Zvolen festival of best university folk dance groups); 7) Turiec (Turčianské Slávnosti Folklóru); 8) Terchová; 9) Svindník and Kamíneka (Ukrainian); and 10) Želiezovce (Hungarian).

PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED

After Igor Moiseyev's first visit to Slovakia in 1946 (and at least 4 or 5 subsequent visits), nothing remained quite the same in Slovakian folk dance. In Slovakia and other Eastern European countries as well, Mr. Moiseyev had a profound influence on the dance and the direction it was to take. The emphasis turned from traditional dance forms to a stylized form rooted in balletics. Advocates stressed that stage presentations and dance theater necessitated a more artistic approach to the dance; hence, the concept of folk-ballet developed. In retrospect, the most positive feature of this movement is that dance reached a very high level of development, and this was especially true in Slovakia. A negative feature is that the emphasis on "performing art" has obscured the traditional dance and perhaps even contributed to the neglect or lack of interest in traditional folklore and its essential scientific study.

The emphasis on choreographic techniques and elements has made the study of simple traditional folk dances very elusive. Moreover, a rather fixed methodology concentrates on learning motifs and elements from various ethnographic regions rather than dances per se. This, coupled with the absence and/or lack of quality audio dance recordings, often results in an undesirable and often frustrating learning experience.

Unlike the Balkan countries, or even Hungarian, Slovakia has remained relatively isolated in the dance world. For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, the Balkans were quite accustomed to foreigners visiting their countries in pursuit of dance. In Slovakia, this phenomenon is still very rare. Also, saddled with the very severe travel restrictions imposed by the Communist regime, no Slovakian dance specialists were allowed to travel abroad to teach. While some colleagues from Hungary, and even Bohemia, were enjoying many such excursions, the very talented dance specialists in Slovakia were denied these privileges. Moreover, they had no idea (and still have difficulty realizing) that their dance is an interesting and marketable product to the outside world.

Another proplem, referred to earlier, is the lack of literature relevant to the dance. Publishing such work in Slovakia is met with many obstacles, to name a few: 1) lack of paper (!); 2) costs of publishing; and 3) bureaucratic delays which culminate in the book being dated before it is even published. While the famous dance ethnologist Dr. Georgy Martin was publishing all those magnificent manuscripts in Hungary, nothing was being produced in Slovakia, even though there were ethnographers of equal status.

The few dance books written have not been translated into English. Some translations have been made of summaries of these books and a few other monographs but the translations are of very poor quality. Therefore, to get accurate information about the dance is difficult, often contradictory, and a long, tedious process. Information gathered for this article represents years of searching and prodding, efforts which hopefully have resulted in a crystallized view of Slovak dance.

OUTLOOK FOR THE FUTURE

There is incredible interest in folklore in Slovakia and it will be interesting to see if this high level of devotion continues in these years following the "peaceful revolution." Already, with the economic crisis, funding for folklore has been cut. Folk festivals, folk groups, and the Slovak Academy of Sciences are all suffering from reduced staffs and budgets. Certainly, this economic deficit will be harmful.

In the past, a motivating factor in belonging to a folklore group was that it offered the possibility to travel to the West. Now, since the revolution, all travel restrictions have been lifted so this incentive no longer exists. However, traveling is expensive for Slovaks and folklore groups may still offer the opportunity of free or inexpensive travel. It does not appear that this factor will affect participation to any great degree.

Now that Slovakia has, in a sense, become a part of the world, young people may develop more diversified interests and these interests may compete with their participation in folklore groups. The increased interest in such things as the English language, computers, radio and television work, and diplomatic services are all evident among young people. In some folklore groups, the beginning dancers must sometimes rehearse five nights a week and it is possible they may be unwilling to devote so much time when other interests beckon.

Many young people have formally studied Slovak folklore in the past and have made it their profession. Such a profession is highly specialized and offeres little opportunity for employment in other parts of the world. It is possible that students in this course of study may decrease in future years.

CONCLUSION

The folk dances of Slovakia (both the indigenous ones and those which come from urban sources, the nobility, and the military) are an expression of art through movement and music, and organically linked to the entire milieu of Slovak folklore and culture. From its archaic beginnings, the dance has been transmitted in varying degrees of intensity from generation to generation. During the period of folklore renaissance (after 1945) it reached its highest level of artistic development within the various amateur and professional folk ensembles. These groups have become the primary and contemporary propagators and mediators of Slovak folk dance. Through television, theater, folklore festivals, and various other programs, these tradition bearers showcase their talents and the Slovak culture. With the evolution of time, dance moved away from its place of birth, the villages, and onto the stage where both performers and spectators vicariously experience the age-old customs of their ancestors and collectively express their national loyalties. This interesting phenomenon is indicative of present trends in folklore throughout Central and Eastern Europe. In Slovakia, because of the intense interest and involvement in performance groups and the presence of extraordinarily talented choreographers, this trend will likely continue with a projection of an even higher level of artistic development.

Considering its simplistic beginnings, folklore has changed dramatically indeed; however, remaining constant is the ineffable beauty and richness of Slovak dance and a beckoning by many in the world to know more about all the wonderful traditions inherent in this vastly interesting culture.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges the following Slovak dance scholars, whose lectures and discussions withe the writer formed the primary sources for this article:

PhDr Stanislav Dúžek, CSC.

Ethnochoreologist, Department of Ethnumusicology

Slovak Academy of Sciences

Bratislava, Slovakia

Mária Mázarová, Zcolen, Slovakia

Ing. Štefan Nosál', Bratislava, Slovakia

Vladimir Urban, Košice, Slovakia

Cyril Zálešák, Bratislava, Slovakia

Also acknowledged for their contributions are PhDr. Milan Lešcak, CSC.; Jozef Lehofsky; PhDr. Jarmila Paličková, CSC. and PhDr. Jasna Paličková, CSC.

The writer acknowledges the eminent Slovak folklore photographer Tibor Szabó of the Slovak Academy of Sciences for contributing many of the photographs and to Brad Messina of Baton Rouge for reproduction of photos.

For assistance in translations the writer acknowledges Elena and Josef Lieskovsky; Vladimir Linder; PhDr. Jarmila Paličková, CSC.; and PhDr. Jasna Paličková, CSC.

REFERENCES

- Elscheková, A., O Elschek, and St. Toth. Slovak Folk Song, Music and Dance. A Report of the Slovak Society of Ethnography of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovenská.

- Ethnografický Atlas Slovenska. Národopisný Ústav Slovenskej AkademieVied and Slovenská Kartografia, Bratislava, Slovenská. 1990

- Mázarová, Mária and Kliment Ondrejka. Slovanské L'udové Tance. Slovenské Pedagogické Nakladetel'sto, Bratislava, Slovenská 1991.

- Zálešák, Cyril. Motivy A Zostavy pre Nácvik Slovenských L'udových Tancov. Osvetový Ústav, Bratislava, Slovenská. 1976.

- Zálešák, Cyril. Prehl'ad Slovenskych L'udových Tancov. Osvetovy Ústav, Bratislava, Slovenská. 1976.

- Zálešák, Cyril. Opissovanie L'udových Tancov. Osveta, Martin, Slovenská. 1956.

PHOTOGRAPHS

- Chorovod from Zvolenská Slatina (Zvolen Region in Middle Slovakia)

- Koleso (Girls' Round Dance) from Dačov Lom (Hont Region in South Central Slovakia)

- Parobské Čaplášovanie (Old Form of Lad's Dance) from Raslivace (Šariš Region in Northeast Slovakia)

- Cifrovanie (Old Form of Lad's Dance) from Očová (Podpol'anie Region in Middle Slovakia)

- Odzemok from Štrba (Upper Liptov Region in North Slovakia)

- Hajduk (Bottle dance) from Zvolenská Slatina (Zvolen Region in Middle Slovakia)

- Cindruška (Girls' Odzemok) from Važec (Liptov Region in North Slovakia)

- Old Form of Couple Turning Dance from Oravská Polhora (Orava Region in North Slovakia)

- Čardáš from Hrinovÿ (Podpol'anie Region in Middle Slovakia)

- Goralský Krešany from Hladovaka (Orava Region in North Slovakia)

DOCUMENTS

- Slovakia, a country.

- Vonnie Brown, an article.

Used with permission of the author.

Reprinted from "Slovak Folk Dances" by Vonnie Brown

in Viltis Magazine, September-October 1993, Volume 52, Number 3;

November-December 1993, Volume 52, Number 4;

January-February 1994, Volume 52, Number 5, V. F. Beliajus, Editor.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.