|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Mysterious Age-Old Zurna

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

The zurna, an ancient folk wind instrument known as shawm in our western culture, has a conical shape with a flared bell at the end. It is played by a double reed, mouthed entirely, the mouth forming a kind of resonator. The player breathes through his nose while playing, producing uninterrupted sound. It is this shawm that is the forerunner of the modern oboe family.

We know the origins of the zurna to be of Central Asia and ancient Asia Minor (the Anatolian peninsula). Facsimiles of the zurna are clearly visible in stone reliefs and drawings left by the Hittites, an ancient and powerful empire established in Asia Minor about 2000 to 1200 before Christ (BCE).

INTRODUCED TO CHINA AND INDIA

The knowledge and fascination with the zurna quickly spread further east and west. In the 16th century, the Central Asian shawms reached China under the name sona. The Kirghiz peoples, found along the far northern reaches of ancient Persia and Afganistanl, leave traces of shawms, the surnaj, and the surna. The shawm of Syria is known as zamr.

With Anatolia being a prominent land route between the East and West, the coastal region of the Mediterranean became a meeting place of many peoples, and whether hostile or friendly, there was an inevitable mutual influence upon the development of musical culture. Turkey not only served as the bearer of traditional Arabic music, but further developed, enriched and influenced this type of music.

Later, with the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Europe, the zurna traveled to the Balkans, Hungary, and Western Europe. There were adaptations of name and shape, but the obvious similarity to the zurna of Turkey was never lost. A very clear example is the zurna of Macedonia. There has never been mention of obvious Turkish-Arabic influence among shepherd flute music of the Spanish Basque and mountain territories of Italy. Forms of the zurna are also prevalent in North Africa. One good example is the zmar of Tunis and Angier.

Origins of the Turkish folk dance are thought to stem from the shamanistic rites of early Central and Western Asiatic Turks, where the shaman would dance to a loud reverberating rhythm set by the davul, a double-membrane drum played with beaters of various thickness.

Gradually, over the centuries, shamanistic rites transferred into folk dance to celebrate age-old joys of birth, marriage, harvest, and religious holidays. The drum carried through as the major instrument of accompaniment. As music developed, other instruments gained importance as melody bearers. It is here, most likely, that the zurna joined with the davul to create a melodious accompaniment to tribal and village folk dance.

Today, the zurna is a strong and inseparable part of Turkish folk music and dance. There is a saying in Turkey, "With no davul-zurna, there is no wedding." Together, the davul and zurna consumate the Turks' greatest expression of joy.

The zurna is not an easy instrument to play. The fingering is relatively simple, like that of a recorder or clarinet. It is the technique of circular breathing that is the most unique and demanding skill. The double-reed is mouthed entirely with the mouth forming a kind of resonator. With puffed cheeks, the player must press and regulate the flow of air onto the reed, while inhaling in a split second through the nose to refill his lungs. This allows for a continuous, uninterrupted flow of sound. An accomplished zurna< player can play indeterminately for as long as his cheeks and lip muscles will hold out. Two octaves are possible to play on a zurna simply by blowing harder and by getting the proper pressure play on the reed.

MAKING A REED, BUYING A ZURNA

It is the reed that is the most important factor in zurna playing. Outside of Turkey, the plant used for zurna reed is commonly found growing in the northern parts of the United States (up-state New York especially), Oregon, and California. It grows three feet to ten feet tall, and along stream and river beds. The reeds are cut, dried, shaved, and fit to the mouthpiece by this method:

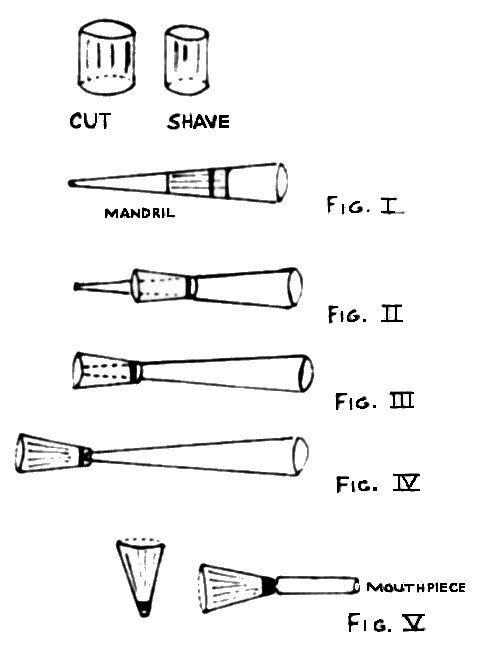

- Cut a 2/3-inch long cylindrical tube piece from the reed and wet it first. Once soaked, shave it patiently and gently.

- Fit the tube to a mandril (sold in music stores to make oboe reeds). See Fig. I.

- Tie a strong bee's-waxed string to the fat end of the reed on the mandril. See Fig. II.

- Move the reed down toward the skinny part of the mandril as you tighten the knot. See Fig. III.

- Move the tube-like reed all the way down the mandril, continuing to tighten the knot. See Fig. IV.

- Take the reed out and quickly put the knot side through the zurna mouthpiece. See Fig. V.

- Finally, very gently press on the round side of the reed to flatten it.

- Put the flattened reed section between the pages of a heavy book overnight to dry.

A zurna mouthpiece and reed are most fragile and should always be kept in a secure box. And always, the reed should be well soaked before playing.

In buying a zurna, one should be bought from a zurna< player and not a musical instrument shop. Most commercially bought zurnas are best for decoration, as they usually do not play well.

In Turkey today, there is another saying, "If you don't rear your daughter well, she will run away with a zurna player." One laughs, but also wonders if women of Turkey don't know best of all!

DOCUMENTS

- Asia, a region.

- Bora Özkök, an article.

- Singing with Zurnas, an article.

- Turkey, a country.

- Zurna, an article.

Used with permission of the author.

Reprinted from Viltis Magazine, June-August 1979, Volume 38, Number 2, V. F. Beliajus, Editor.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.