|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Breton Folk Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

There are indications that ever since humankind first learned to move to rhythm of sound, either for self-pleasure or as a ritual gesture to propitiate the various immortal dieties, there has been dnce of some form on the wild and scenic peninsula of Brittany. Mythology of the ancient Armorican's hints that the circles of upended granite pillars, like those of Stonehenge in England, represent various dance arenas, or even actual dancers frozen for eternity in the act of performance of some ancient line dance.

Bretons performed in demonstrations for the court of the Medicis, and, following the famous Edict of Nantes and in his victory over Spain in 1598, the Bourbon King, Henry IV, is said to have learned the Passadied de Betagne or Branle, which was the provincial dance of Upper Brittany. Lower Brittany at that time favored the Triori, a very vigorous agricultural dance of the time, which called for much leaping and agility.

|

According to Curt Sachs, some of the ancient Breton dances were ceremonial "medicine dances," done by the primitive men there to drive the illness from the sick people. This would indicate that the idea of dancing as a form of entertainment to please the gods was a universal man-thought, found throughout the world in primitive societies. Ethel Urlin, writing in 1914, suggests that many of the dances of the Bretons can be traced back to the nature-worship of their Celt ancestors. This could well be true, for the Celts roamed far and wide over Europe and Asia Minor, and this could perhaps explain why many Breton dances remind us in some manner of some of the dances of the Balkans.

In the 19th century, a writer says that the Breton's love for dance is a historical development – one in which women shared the spirit of the dance equally with the men, although ". . . the men leap, yell, and fling themselves about . . . while the women are reserved in manner . . ." Here possibly is an indication of continental European influence on Celtic life and the male macho – for those Celts who retreated into the British Isles and from whence came the Bretons – retained for centuries the original Celtic ideology of equality for both sexes. Some of the most noted Celtic warriors were women.

But back to folk dance. There were many occasions for folk dancing. Local festivals, weddings, pardons, seasonal holidays of an agricultural nature, such as the start or end of the harvest or planting, were causes for celebration. Indeed, some of the dances and holidays they represent do seem to coincide in the time or subject with those which we look upon as particular to England and Wales. There is Pilar-lan, a dance to beat the gorse; Stoupik, at the end of the hemp-stripping work; a sword dance is represented by some of the stick dances; Jabadao is supposed to represent the roistering and the rumble of a coven at the Witches' Sabbath; Jibidi and La anse de Guissent were astral dances.

While some of these dances have retained their original connotations in a sense, others have lost their original symbolisms in the exchange between the courts of Paris, Nantes, and Remes, and taken on new meanings and forms. The nobility, attracted by some special Gavotte, Branle, or Polka. They would lose a lot on the way, of course, but then they became the "folk dances" of the classes higher up. Meanwhile, on the other hand, the middle and upper classes of the rest of Europe (and later, America), looked with disdain on their own cultural assets and turned eyes toward the elegance of Paris! (So, what's new? The Highlife dances of Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Haiti came first to our black South, thence to our American flaming youth and teens as Charleston dances and Rock – the adults liked them and adopted them for jazz and disco, and they eventually wind up on page one of the Times' View section or the society page of the Evening Outlook at a Bel Air party. The thing is, they don't look the same as they did in Accra or Port au Prince – and neither did the Parisian versions look the same as those dances of the Cournaille. Of course, the Bretons also borrowed from the "haute monde" and those dances are as popular in, say, Quimper, as is rock-and-roll in Zagreb.)

A most important celebration in Brittany (as in most of Europe) is St. John's Eve. On that occasion, dancers and singers gather around a fire on the public common – or, for that matter, wherever a group of celebrants may have a spot to get together. Marcel Dubois tells us how they are called together at the sound of horns, or by the call of an unusual sound from large cauldrons in which a little water has been poured. Reeds are strung taut across the tops of the bowls and are stretched and rubbed, much like the movement of milking a cow, which causes the water to vibrate, emitting an eerie sound that may be heard for miles. It is then, 'tis said, the souls of the dead come back upon hearing it, to warm themselves before the Midsummer Eve bonfire. Meanwhile, the young women of marriageable age, seeking a husband, take turns leaping over the flickering and waning flames. Needless to say, it doesn't take much imagination to guess what happens to their hopes should they not quite make it.

A "dance of the threshing floor" has a dual purpose. First, it is an excuse to dance in celebration of the proposed building of the floor – and secondly, the dancers are carefully "shepherded" into positions to dance on the spots that are most needed tamping down, to make a nice, level foundation with the stamping feet of the celebrants. Then there are weddings. They may last as long as three days, with the dancing starting immediately after the wedding party leaves the church – the bride and groom initiating it as with our wedding waltzes – and stopping along the way at the wine shops, the banquet, and so on. By the third day, the poor people of the parish have joined in and everybody dances the Gavotte des Pauvres.

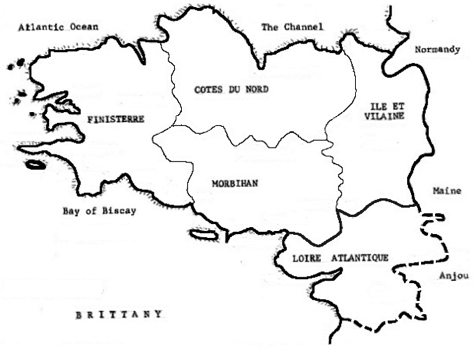

Although folk dancing has diminished in a lot in eastern Brittany and many dances have been lost forever, dancing of a spontaneous nature may be found more easily in the west. In some places even there, regional dances have begun to disappear, but the traditionalists are beginning to hold the line and revive the old dances again, buoyed up perhaps by by the recent upsurge of Breton nationalism, especially over the past two decades. (Or, could it be vice-versa – that the increase in the performance of old Breton dances and music has triggered a rebirth of Breton nationalism? Anthems will do that, you know!) Anyhow, real folk dancing from the soul may be found especially in the areas of Basse-Comouaille, the hill country of the Black Mountains and the Monts l'Arree, and the Vannetais district. These areas also have their particular styles. The Vennetais is graceful and poised, with smooth arm and leg movements, uncomplicated – tending to be more quiet as one nears the coast, livelier as one moves inland toward Pontivy. The dances of the hill people are somewhat more jerky and rapid, even leaning to the acrobatic. The gorse beating dance, Pillar-lan, is one of the stamping dances of the mountains.

In Basse-Comuaille, the dances are characterized by gracefulness, ease, and a smooth movement. The Gavotte du Pont Anan, imitating the undulating waves of the sea, is a colorful example of the classic dances of Brittany, along with the Ridée de Baud of the Vannetaia. The term "gavotte" by the way, originated in the Alpine area of France and Swiss French, among the Gavots, a mountain people, and spread throughout Western Europe. The Breton gavottes are very different from those of the rest of France and of those of the European courts. In some areas, as in Upper Cormouaille, they are danced in an open or closed circle and often sung – while in Lower Cornouaille, they will be in groups of four, danced to the tune of the binioù [a bagpipe] and bombarde [a double-reed wind instrument]. In some towns, everybody is equal, while in others, such as Quimper, as in Yugoslav dances, it is considered to be an honor to lead the Gavotte. In fact, in the Gavotte du Pont Aven, which is a set of two couples, the dancers go though their steps and gyrations and the first man may pass the lead to the next and back and forth as in a Greek Syrto. A popular dance of this type and area is the Gavotte de Quimper.

Jibidi-Jibidao is possibly the most popular dance in Brittany – certainly in Cornouaille and also one of the simplest. The Pilar-lan (already mentioned) is danced in two lines, men facing women. The Trihoris or Breton Passapied dates back some centuries. There is a Danse Pasturelle in the region of Carhaux for men that has descended from an old Christmas drama – a Passapied also. There is a couples-processional in the Guingamp district that could be a distant relative of the Cornish Helston Furry, called the Derobee, danced in a different rhythm from most dances of Brasse-Bretagne. The Ridée is a cheerful dance in a circle for as many as will – sometimes taking in the entire population of the village, danced to singing and/or instruments, and varies from town to town. In St. Brieuc, a popular dance is Les Pattes en Haut, for circles of couples or a quadrille wherein the men will lift their partners high in the air at a given moment like similar Central European dances. And, of course, the Farandole is danced in Brittany as well as in other parts of France.

It is unfortunate that Breton dances have not been more a part of the international folk dance picture in America. It may be due in part to the fact that until quite recent stirrings, Breton folk culture had not been heard of much beyond the confines of its own territories. Perhaps also, there has been a lack of qualified instructors in the dances of that region. And also, perhaps the misconception that dances of Brittany are too simple has deterred folk dancers from trying them. But Brittany has folk dances for all – plenty of line dances at various levels for the "line dance" crowd; couple dances for old or young; set dances for those gregarious ones who enjoy dancing together in a challenge quadrille; and some men's dances that call for a lot of the same stamina needed for those lively dances of the Eastern part of Europe.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Burchenal, E. Folk Dances of the Old Homelands. G. Shirmer, New York, 1922.

- Cullen, M. – "Folk Dancing in Brittany." S.I.F.D. News, London, 1977.

- Duggan, A.; Schlottman, J.; Rutledge, A. Folk Dances of European Countries. Barnes, New York, 1948.

- Galbrun, E. La Danse Bretonne. Pub., Carhaix, France, 1936.

- Horst, L. "Pre-classic Dance Forms." The Dance Observer, New York, 1937.

- Marcel-Dubois, C. Dances of Brittany & Bourbonnais. Parrish, London, 1950.

- Sachs, C. World History of the Dance. Norton, New York, 1937.

- Sweetland, G. "Briezh, Summer 1976." S.I.F.D. News, London, 1976.

- Urlin, E.L. Dancing, Ancient and Modern. Appleton, New York, 1937.

- Walker, H. "France Meets the Sea in Brittany." National Geographic Society, Washington, DC, 1965.

DOCUMENTS

- An Dro, a dance.

- Ann Dugan, an author.

- Avant-Deux, a dance.

- Bannielou Lambaol, a dance.

- Brittany, a region.

- Curt Sachs, an author.

- France, a country.

- Le Bal de Jugon, a dance.

Printed in Folk Dance Scene, September 1978, and titled "Folk Dance in Brittany."

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.