|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

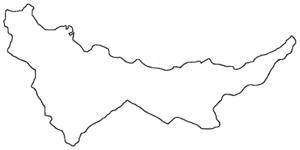

Efxinos Pontos

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

Tommy Toromanidis has introduced the Pontic Greek community at all the Spring Folk Festival concerts. And, although I've known Tommy for some five years, danced to Andy's lyra, and drunk with Nick, I never really got a sense of where the uniqueness of their folk culture came from until I visited Greece.

Tommy Toromanidis has introduced the Pontic Greek community at all the Spring Folk Festival concerts. And, although I've known Tommy for some five years, danced to Andy's lyra, and drunk with Nick, I never really got a sense of where the uniqueness of their folk culture came from until I visited Greece.

What came through time and again, with all the people I met, was that historical facts and figures can never capture what those events do to the lives of the people who lived through them. for the Pontics, as for so many of the peoples in that area of the world, it was a tale of constant battle for survival as they were victimized by a constant stream of massacres and cruelties that were eventually resolved by the exchange of populations. That agreement returned all Greeks living in Anatolia to Greece, and all Turks living in Macedonia to Turkey (with exceptions). And so, in January 1923, some 1.8 million people, Greeks and Turks, were forced to leave the villages, towns, and cities settled by their ancestors as many as 2,000 years earlier, and forced to take up roots elsewhere.

The 20th century has sped up the process of industrialization and mechanization to a point of disbelief. But, for the Pontic community, uprooted from their homeland, the music, songs, dances, language, ways, and memories were the only tangible things they were able to take with them when they left. With these they started life over again. And so, the inroads of pan-Hellenization, so evident in other areas of Greece, have not quite overwhelmed the Pontics yet. Their lyra is the only one of its kind in Greece. The sound of the music is uniquely theirs. The dances with their frenetic and warrior-like qualities, at once driving and strong, with great subtlety, are in a class by themselves in modern-day Greece.

Whenever they have performed, I've been asked repeatedly, "Who are the Pontics?" They are Greeks who emigrated from Greece to the Black Sea Coast of Asia Minor, establishing settlements there some 2,000 years ago. They named their area Efxinos Pontos ("hospitable sea") as a psychological edge over a sea that was anything but hospitable to them. When times were difficult they immigrated to Southern Russia and the Caucasus where they became active merchants and businessmen.

World War I and the subsequent war between Greece and Turkey led to the transfer of populations agreements in the Balkans and in Turkey. And, whereas Russia would have been the traditional place place of refuge for these Orthodox communities to emigrate, this alternative was closed to them because of the Bolshevik Revolution. So, as of 1923, Efxinos Pontos no longer had a Greek population. Some 400,000 Pontics were jammed into any seagoing vessel to be returned to a Greece that neither they nor their fathers or grandfathers had ever seen.

Resettled in emptied Turkish villages, or in tarpaper huts in newly established shanty towns, most were sent to Northern Greece, to Macedonia and to Thrace, to play out their traditional role of akritas ("defender of the borders"). The first wave of immigration to the United States came at this time with the first group settling in Akron, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. A second wave of immigration to the United States came following World War II, and particularly in the last ten years.

The Ponti left Asia Minor playing their traditional musical instruments – the lyra (three-stringed instrument), angion or dankiyo (bagpipe), zourna (wind instrument), and daouli (large drum). In Greece, the latter two instruments have disappeared in the Pontic communities, having been replaced by the more popular Greek-type orchestra made up of clarinet, accordion and drums, with the traditional Pontic lyra added. In the villages, the drum is a large daouli strapped over the shoulder to be easily carried for processions, and having a cymbal on top. In the towns and cities there would be a small and large drum set on the ground. This would be the most typical orchestra for weddings, holidays, and Pontic fraternal club dances.

In the United States, as in Greece, the lyra would be played at all occasions with electric amplification the latest addition. Although there may be four or five lyra players in a room, only one will play and interpret his music at any given time. The lyra would be there for all social gatherings, whether in the home, kafenion (café), or banquet hall. It also would be used to accompany the different performing groups exhibited on television or for any other occasion.

In some villages in Northern Greece, the angion would be found. While attending a wedding, Ethel Raim and I were sitting in a kafenion, having a drink, waiting for the newly married couple to return from church. An angion player accompanied a group of men who were singing, and then he played for their dances. But the angion is neither as commonly found, nor as popular as the other Pontic instruments.

In Thessaloniki, there are two dance halls where several hundred people will gather on weekend evenings to eat, drink, listen, and dance to Pontic music – played by "professionals." I have never seen anything like it elsewhere in the Balkans. People of all ages, teenagers to seniors, sitting around in a huge room, while the dancers were all crammed into a dance space doing Tik, Kots, Sera, Letchina, or any of the other Pontic dances.

What distinguishes this group from other Greeks? They came from living in Asia Minor, with a dialect very different from other Greeks, a costume more similar to local inhabitants on the Black Sea Coast than with any group on mainland Greece, and they returned to an ambivalent reception by the local Greek populations. What distinguishes this group is that they "stick together," as I was constantly informed. They take care of each other, look after each other, and are attentive to their community's needs. Some say that the Pontics have preserved the oldest form of what is Greek. This I don't know. I do know from other groups with whom I have worked, and particularly here in the United States, that when a majority group leaves its sanctuary, becoming a minority group elsewhere in another land, what is theirs is either held onto tenaciously, with little change, is completely swept away, or is involved in an exchange and some merging with the folk expressions of the neighboring people.

Why do they leave Greece nowadays? They leave as do other Balkan ethnic groups – because there is money to be earned in the West. You can earn more money by selling frankfurters on a New York City street corner; making slippers in a factory in Norwalk, Connecticut; working in the meat department in Grand Union in Dobbs Ferry, New York; or working in construction in Australia or West Germany. And so, a village having a population of some 2,000 people ten years ago, may now have less than half that number, and of these most are either over fifty or under ten years of age.

What will happen? I have no idea. For the communities in Greece, as in so many communities in Yugoslavia, Turkey, Spain, and Portugal, emigration is the greatest enemy. For these transplanted communities here, they at first form societies to protect their newly arrived members. Whether or not the next generation, or even the present one, as it becomes increasingly more comfortable with this new land, learns the language, integrates more easily, and gains increased access to "American" society, will choose to stay connected to their old world compatriots – only time will tell.

What has struck me by seeing the Pontic experience more clearly is the great injustices and tragedies that have been perpetrated on minority groups the world over in recent years. As Mr. Harry Psomiadis said, "The 20th century will not be known for its generosity towards minorities." And that is the sad truth. And the century isn't done yet...

The material presented here was gathered by Ethel Raim and Martin Koenig in work done in the Pontic-American communities and in the Pontic communities in Greece.

DOCUMENTS

- Greece, a country.

- Martin Koenig, an article.

- Pontos, a region.

Used with permission of the

Center for Traditional Music and Dance Archive, www.ctmd.org.

Printed in Balkan-Arts Traditions, 1974.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.