|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Balkan Dance

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia |

Periodicals | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

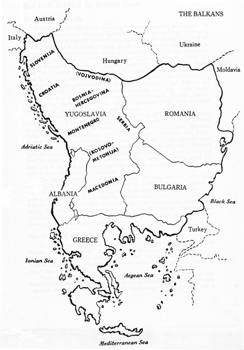

Balkan is a Turkish word meaning "chain of wooded mountains." In the early history of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, the word was applied to a massive chain of heavily forested mountains that cut through what is today the republic of Bulgaria. During the five-hundred-year Ottoman occupation of the Balkan Peninsula (from the fourteenth through the nineteenth centuries), the name was gradually applied to the whole region. Today, the Balkan Peninsula includes the territory south of an imaginary line drawn from the northern tip of the Adriatic Sea eastward to the mouth of the Danube River on the Black Sea. However, such a definition is inconvenient, because it breaks up politically defined units; more simply, the Balkans are made up of Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia itself was a federation of the republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Hercegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Montenegro, with two so-called "autonomous" regions, Vojvodina and Kosovo-Metohija (Kosmet).

The history of the Balkans, the "Powder-Keg of Europe," is confused and chaotic, and for long periods was poorly documented. The wooded mountains have watched the comings and goings of Thracians, Illyrians, Celts, Greeks, Romans, Slavs, Western European Crusaders, and Turks, as well as many obscure ethnic groups, each of which has left its individual stamp on the physical and spiritual landscape. Strong cultural influences have been exerted by Rome (both pagan and Christian), Byzantium, and the Ottoman Turks. The Balkans have always been a meeting place for East and West, both politically and culturally; as a result, the whole peninsula is an amazing land of contrasts.

The Slavs dominated the Balkans from the sixth century until the Middle Ages, when most of the area fell to the Ottomans. Individual national groups began to re-emerge in the nineteenth century as the Ottoman Empire declined and withdrew, and the establishment of the separate Balkan States since that time has been a painful, often tragic process. Between the World Wars, there was relative solidification of most national boundaries. During and after World War II, all the Balkan countries except Greece became communist governed.

THE PEOPLE OF THE BALKANS

As we can see, the Balkan people cannot point to a truly "pure" ethnic history; however, the following general groupings can be made.

- Greeks: The Greeks inhabit the Greek mainland and most of the Aegean Islands; they have the longest recorded history of any people in the Balkans.

- Slavs: The Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Macedonians, and Bulgarians represent the Southern Slavs, who came to the peninsula in the fifth and sixth centuries from beyond the Carpathian Mountains. The Bulgarians are a mixture resulting from the absorption of native Slavs of a conquering Central Asian tribe called the Bulgars.

- Daco-Romans: These include the Romanians and the nomadic "Vlachs," who, though they speak a language derived from Latin, are actually a fusion of several ethnic strains.

- Albanians: Presumably, this group descended from the Illyrians, who migrated from the western Balkans to the mountains when the Slavs arrived.

The literary languages in the Balkans are Romanian, Slovenian, Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Greek, Albanian, and Bulgarian, but the linguistic situation throughout the area is very complicated, with great numbers of dialects having developed.

The five hundred years of Turkish occupation constituted the Balkan "Dark Ages." There was no native intelligentsia to speak of, aside from a few semi-literate monks. The Renaissance and other great European cultural movements went unnoticed by the people subjugated by the Turks. Folklore and the folk arts were the sole substance of artistic life. For this reason, the Balkans today offer an amazing wealth of folk material – songs, dances, costumes, tales, epics, and other folklore genres.

Most of the Balkan peoples have a strong patriarchal way of life in a society where the group or collective is more important than the individual. The institution known as the zadruga, for example, only recently disappeared in Yugoslavia. Under the old zadruga system, all the male members of a family or clan brought their wives to live with them in a steadily growing household that often served as a residence for three or four generations of people, all working together and presided over by the eldest male member.

The Balkan peoples differ in character, but pinpointing these differences is difficult. Supposedly, the Slovenes are the Hollanders or Germans of the Balkans – clean, orderly, and intellectual – while the Serbs are the "hotheads," being emotional, proud, and sensual. Bulgarians have been characterized as stolid, hard-working, persistent, and affectionate. The Romanians are jokingly portrayed as parsimonious, the Montenegrins as heroic but a bit lazy, the Bosnians as slow, etc. These characterizations can be dangerously inaccurate.

There are few really large cities in the Balkans, and even today village life follows the normal pattern. Daily life in the village centers around the needs of the farmer or herdsman. Spring, summer, and early autumn are devoted to hard work. Remnants of old ritual holidays to encourage good planting, harvests, and healthy flocks still survive today, blended with church holidays such as Shrovetide, Easter, St. John's Day (Midsummer), Christmas, and New Year's. Weddings traditionally take place in the fall, as soon as the parents of the bride and groom feel assured that the fruits of the year's labor have been abundant enough to allow the enormous expenses of the wedding celebration. In the central Balkans, the peasants stay indoors for most of the winter, devoting themselves to family gatherings, spinning-bees, etc. Worn tools are repaired and much time is spent swapping stories.

DANCE IN THE BALKANS

Historical View

A historian in any field must rely on surviving documents and monuments for his raw materials. The historian who records and analyzes past events turns to contemporary writings, archaeological findings, and, ultimately, to his own "informed conjecture."

The dance historian approaching the Balkan Peninsula is faced with a very meager supply of sources. As he examines manuscripts dating back to early Balkan history, he must be satisfied with such oblique statements as "devilish music making and revelry among the folk." Graphic representations of the dance, however, do exist. For example, the fourteenth-century fresco in the church of Lesnovo (Macedonia) shows that the circle dance with hands crossed in front and accompanied by drum and stringed instrument was known to the artist.

Greek art, of course, abounds in portrayals of the dance, and the works of Homer and Lucian contain descriptions of ancient Greek dancing. Scholars have been able, with probable accuracy, to trace the development of the orgiastic Dionysian ritual dances up to the flowering of Greek drama with its typical chorus. (The Greek word choros still means "dance" today.) The exact degree to which these ancient references may be associated with the Greek folk dance today, however, is not altogether clear, especially since much time has elapsed and many cultural changes have occurred.

During the Romantic period of the nineteenth century there was an awakening of interest in the "folk." All over Europe attention turned to local peasantries, whose culture was deemed somehow purer and more valid than that of the cities. In the Balkans, as well as elsewhere in Europe, researchers scoured the remote rural areas, writing down precious folk songs, tales, and customs from elderly peasants. Although none of these early folklorists was particularly interested in recording dances as such, many did write down dance tunes or made reference to the role played by dancing in certain folk customs. Sometimes these romantics would pen highly sentimantal descriptions of "fair maidens and bold rustic lads quaintly dancing on the village green." In the Balkans, those notations and descriptions increase as we come nearer the twentieth century.

Although we cannot reconstruct any nineteenth-century folk dances from these writings, we can learn from them something of the general character of Balkan dance of the period. We know, for example, that the circle and line dances were done throughout the Balkans, and that dances of ritual origin were very much alive at the time. We know that many dances were accompanied by singing or by various instruments. The people of the Balkans definitely possessed an astoundingly rich store of dance material.

As the Balkan peoples freed themselves one by one from the Ottoman yoke, setting up their own national boundaries, aristocracies, and national cultures, they turned to local folklore for inspiration. Folk traditions were the only native cultural heritage they had. Folk-epic themes became the basis for literature, and folk melodies were woven into concert compositions. In many cases, urban ballroom dance masters sprinkled local folk dance movements into the fashionable quadrilles and danses de salon, which came directly from Paris and Vienna. Dances "in the folk spirit," in circle or line formation, were done at all upper-class functions; the highest ranking person present (often the king or queen) led the line. Examples of old ballroom dances in the folk spirit are Hrvatsko salonsko kolo (a six-figured dance with elements of the quadrille and modified steps borrowed from Croatian folk dance), and the Romanian Hora unirii (Hora of the Union), celebrating the union of Wallachia and Moldavia into the Old Kingdom of Romania (1858–1861).

In northern and western Europe, detailed descriptions and prescriptive instructions for folk dances appeared toward the end of the nineteenth century. Analytical choreographic descriptions of the true Balkan folk dances, however, did not appear until the twentieth century. The first volume of the monumental collection Narodne igre (Folk Dances) by the Yugoslavian sisters Ljubica and Danica Janković was published in 1934; it is the first really systemic and comprehensive record of Balkan dance. Even in 1934 there was the feeling that many dances had already been lost, and that jazz and Western taste in the Balkans had done much to reduce the native repertory. In Romania and Bulgaria a number of fair books on folk dance appeared between the two World Wars. Greece produced its first real book on folk dance in 1940, but Albania has not yet published an authoritative work.

When we speak of the enormous loss of dance material within the last century, we are speaking in relative terms, however. Even with its reduced repertory, the Balkan Peninsula still possesses a far richer store of dance material than any other area in Europe of comparable size and population.

Dance in Daily Life

Music, song, and dance are fundamental components of any celebration or get-together in the Balkans. Each village has one (and often more than one) dancing place in the central square, in the churchyard, or at any level crossroads or meadow. Dancing is often done in homes, too, especially at winter gatherings or close family affairs In southern Bulgaria and Macedonia, dances are often done on a second-story čardak (a verandah-like porch around more than one side of the house).

On Sunday afternoons and holidays the whole village meets to drink, gossip, sing, and dance. To a native of the Balkans, the word for dance (kolo, horó, horă, etc.) has a much broader meaning than it has for us. For a native Slavonian (a resident of Eastern Croatia), the word kolo (wheel) connotes the whole complex of social activity that goes on around the dancing. His most famous dance, Slavonsko kolo is, in its native setting, a many-faceted social event. American folk dancers learning this dance can focus their attention on the technical side of the "choreography"; the Slavonian looks on the steps and sequences as a very minor part of what he thinks of as his "kolo." As the dancers shout poskočice (clever, often biting, improvised rhymes) back and forth, the current life of the village is revealed, the personalities of all the villagers are displayed, and outside the circle of dancers the older people who sit around observing, drinking, and gossiping are an integral part of the "kolo."

Besides the regular Sunday-afternoon festivities, special national and church holidays, particularly the Saint's Day of a given village, are also celebrated with song and dance. At a typical Balkan fair, people come from miles around to gather at one village. It is not unusual to see a whole field or meadow covered with many circles of lively dancers, each circle with its own musicians. In Serbia it is customary for a fellow who wishes to lead a dance to pay the violinist or accordionist (usually one of a number of Romani come to town just for the occasion) a certain amount of money and then, accompanied by this musician to proceed to gather a line of dancers on his left. Šetnja is a kolo often done at such times. The length of the dance is determined by how much music the musician is willing to furnish for the price paid. Of course, the leader has the right to nane the dance he wishes to lead.

Weddings are the events at which the greatest amount of good dancing can be seen. A wedding is a village affair (even the uninvited often attend), and frequently lasting several days; everyone has ample opportunity to exhaust many times over the village dance repertory. In those areas where the people still adhere to the traditional old wedding customs, each episode of the preparation and ceremony (coifing the bride, shaving the groom, bidding farewell to parents, etc.) is accompanied by special songs and dances. In the close atmosphere of the wedding celebration, older dancers who might not perform at ordinary festivities often perform dances rarely seen among members of the present generation.

Smaller household gatherings are also occasions for dancing. An institution common to the central Balkan area is the "working-bee" (called sedeljka in Serbo-Croatian, sedjanka in Bulgarian, and sezatoare in Romanian). These are get-togethers, primarily of women and girls, that begin in August and are held regularly throughout the winter. The women and girls sit, each with her own embroidery, spinning, etc., and sing songs. The young village youths may visit them during the evening, usually with a musician, so that a little dancing is generally part of the evening.

Remnants of old ritual dances are found throughout the Balkans. These dances are distinguished from ordinary "recreational" dances in that they are performed only in connection with a specific calendar date or special recurrent event and form a part of a ceremonial related to old superstitions and beliefs. Wedding dances, as well as traces of old dances associated with funerals and christenings, fall into this category. the Călușarii and the Rusalii of Macedonia and Bulgaria are spectacular dances for trained groups of men, performed at specific times of the year; they contain elements traceable to ancient brotherhood societies and initiation rites. The Nestinarsko horo of Bulgaria (also known in Greece as Anastenaria) is a fire-walking ritual unique in Europe; it is apparently derived from old purification rites now incorporated into a Christianized culture. In Serbia, girls called Dodole go about the village during droughts and perform special songs and dances to bring rain. At each household they are doused with water as a means of ensuring that rain will come.

The dance in the Balkans is an especially important vehicle for establishing one as a personality among one's contemporaries. Good dancers are greatly admired by all the people of a village, and – particularly in the southern Balkans – the role of leader of a line must be fulfilled with skill and responsibility to the tastes of the other dancers. Men in particular expected to be fine dancers; women tend to dance with more restraint. Formerly, social life was such that men and women danced in separate groups. Certain regions still preserve traces of this in special dances for men or women, and in the segregation of sexes to specific parts of the circle or line (men on the right end, women on the left, etc.).

Competition is an important element in much Balkan dancing. In many areas the ability to perform clever improvisations and outdo rival dancers is a mark of a good dancer. The Bulgarian Rŭčenica, done either as a solo dance or with male or female partner, is a fine example of this. Often a young man will leap from the sidelines to outdo someone who has been dancing for the crowd, or a girl may come forward and challenge some young man to impress him with clever variations. Usually the competitive element is more important than the erotic in these cases. Different regions in the Balkans vary, of course, in all these respects, and it is impossible to make universal statements in a limited space. Strenuous competition dances are rarer in Croatia, for example, than in other, more southern areas.

Collectivity is also basic to Balkan dancing. In most group dances all the performers do essentially the same movements at the same time – any individual variations or improvisations are restricted in that they must in no way hinder the movement of the rest of the line. In observing the popular Serbian dance U šest koraka, one may be amazed to see that every dancer in the line is doing something different. A closer look, however, reveals that all the dancers are adhering to the basic pattern and never perform movements that will interfere with the direction and rhythm of their neighbors' steps. Hence, no leader would throw in a flashy step to gain attention – he is still bound to tradition.

Although even the most remote Balkan villages are now being exposed to modern cosmopolitan ballroom dances, the older native folk dances are still very much alive. One of the effects of the long Turkish domination in the Balkans was a minimum of differentiation in taste between villager and city-dweller. Popular tunes on Balkan radio stations usually deal with village themes. A Sarajevo businessman on his way to work may be humming a hit tune entitled "I Tend My Sheep by the Morava River." Even in chic Belgrade night clubs the kolo U šest koraka can regularly be seen; the dancers are dressed in the latest fashion; they join hands and form long curved lines about the dance floor. In Greece, too, dances such as the Syrtos-Kalamatianos have assumed a national character and are regularly danced by city-folk on their nights out.

Balkan folk dances differ from those of most other parts of Europe in that they are still today a living, breathing, ever-changing ingredient in the lives of the people who perform them. This is not the case in most of Western Europe, where what we call folk dances are reconstructions or preserved, frozen forms; they were long ago standardized and written down, and are now in the hands of special societies and performance groups entrusted with their preservation.

In the Balkans, the old traditional circle dances, as complicated as they may be, are still the natural form of dance for today's villager. Since World War II, amateur and professional stage performance groups have been formed in most Balkan towns in an effort to keep the local folk dances alive. This self-conscious learning of the dances has not only revived interest in the older dances, but also, unfortunately, has done much to overdo them. The ultimate result of this new emphasis is difficult to predict; it will probably preserve the dances in a fixed, standardized form, and some day the old dances will have died out in their natural settings and will have to be taught in formal rehearsal halls. When this happens, the folk dance in the Balkans will have reached the same stage it did in Scandinavia and other parts of northern and northwestern Europe years ago.

"ANATOMY" OF BALKAN DANCE

The most common form of folk dance in the Balkans is the group dance, in which dancers are linked in a circle or line. This was a universal form of the dance throughout Europe before the advent of the couple dance. The Ottoman occupation of the Balkan Peninsula served to isolate these countries from cultural importations; dances such as the quadrille, waltz, polka, and schottische were hence totally unknown in the Ottoman Balkans, and only in the last many years have they entered the Balkan repertory as imports.

The circle dance is known by the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes as kolo, by the Macedonians and Montenegrins as oro, by the Bulgarians as horo, and by the Romanians as hora. In northern regions the circle is usually closed. In most other parts of the Balkans the circle is generally open; there is a leader and an "end man" (called kolovodja and keć, respectively, in Serbia). The open circle may often develop into a straight line or a serpentine (the Slovenian Metliško kolo and the Greek Tsakonikos are two examples).

Straight lines, rather than curved, are found in Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, and Romania. The name lesa (fence or hedge-row) is the name given in western Bulgaria and eastern Yugoslavia to the small straight line or a serpentine (Slovenian Metliško kolo and Greek belt dances (Serbian Čačak, Bulgarian Mŭško trojno).

In Croatian drmeši (shaking dances) the hands are often crossed in back or in front of the nearest neighbor, linking with the second person over on either side. this so-called "basket hold" is found elsewhere in the Balkans, notably in the Greek islands. In Macedonia, dancers often hold handkerchiefs or strings of beads between them instead of holding hands.

Dances in longways formation are found occasionally in the Balkans, but principally in areas historically influenced by Western Europe (the Adriatic islands and the Italo-Yugoslav border area).

Couple dances in the Balkan Peninsula are of two basic categories: those with partner contact and those without. Into the first category fall dances that have developed primarily in the northern areas closely tied with Central and Western Europe (Slovenia, Croatia, the Vojvodina, Transylvania), as well as more recent dances based on the polka, waltz, mazurka, cárdás, etc. Here the familiar shoulder-waist and ordinary ballroom positions are used.

The couple dances in which there is no (or minimal) physical contact seem to be older and more widespread. Examples are the Bulgarian Rŭčenica and its relatives Katanka in Serbia and Geamparalele in Southern Romania. In these dances partners dance individually near each other, the man often doing agile show-off steps, the woman dancing with an atitude of challenge. The Albanian Shotë, the Montenegrin Igrane po crnogorski, and the Greek Zebekiko have this same feature, though styling and character differ greatly. In all of these dances, body contact is either non-existant or, at the most, limited to linking elbows in a turn, twirling the woman briefly under the joined hands, etc. In the main body of the dance there is no physical contact.

Dance tempos vary greatly throughout the Balkans; they range from the extremely slow, deliberate dances of Macedonia to the lightning-fast dances of the Bulgarian Šopi. A common feature in the dances of Albania, Macedonia, Northern Greece, and parts of Bulgaria is an accelerated tempo. A dance such as the Macedonian Lesnoto, for example, begins rather slowly and gradually speeds up to a very quick climax. In these cases the basic step pattern usually remains the same, but the style becomes livelier through the addition of extra hops and other choreographic embroidery.

Balkan rhythms have always interested dance scholars, because the Balkan peoples – especially the Albanians, Macedonians, Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgarians – relish dances in irregular rhythms, such as 5/16, 7/8, and 11/16. Béla Bartók, the Hungarian composer and musicologist, was among the first to notate these rhythms properly; he called them "Bulgarian rhythms." Musicologists who had previously found these rhythms among the peoples of the Middle East had given them the name aksak, from the Turkish word meaning "limping."

REGULAR RHYTHMS

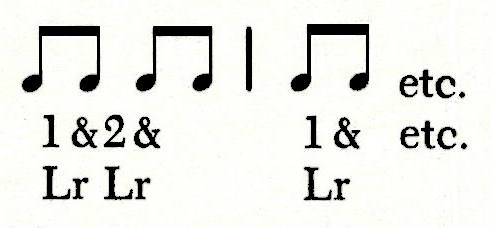

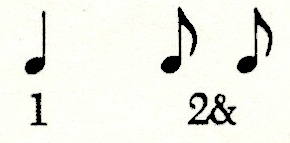

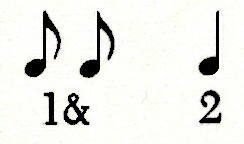

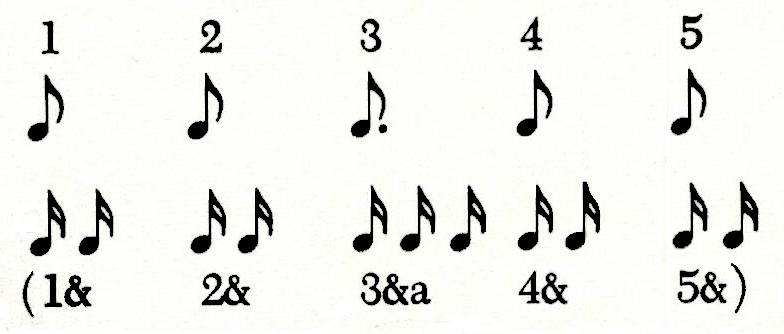

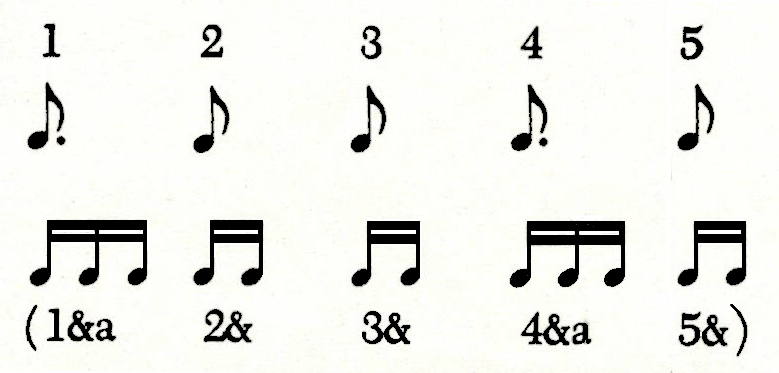

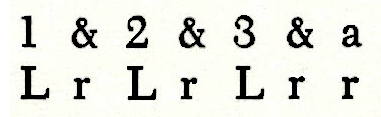

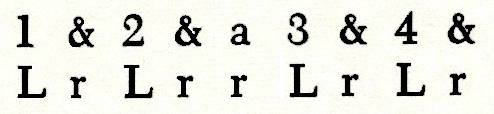

The 2/4 meter predominates in Balkan dance music, just as it does in the rest of the world. Often the Balkan people will perform highly syncopated steps in this rhythm, giving it a special coloring. The Romanians are particularly famous for this: against a brisk 2/4 tune they frequently perform unbelievably complex syncopated patterns of steps, stamps, and pauses. Some of these patterns are eight or more measures long. A common pattern in the Balkans, from Croatia through the Greek islands, is a three-count step pattern of one measure, counted

instead of the more familiar

The 3/4 meter is rare in Balkan music (with the exception of the Slovenian mountain regions). The Greek-Albanian Tsamiko is in a slow 3/4 meter far removed from waltz tempo. In southwestern Bulgaria it is found occasionally (Igra na dvamina), and in Dalmatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina, the so-called nijemo (silent) dances have a 3/4 count, although the lyrics of songs sometimes used to accompany them are in 2/4 (Vrličko kolo, Starobosansko kolo, etc.). Old-time musicologists and collectors unfamiliar with the 7/8 rhythms often notated such melodies in 3/4 meter by adding various signs to show that one of the beats was subtly held longer than the rest. Hence, older collections show many more melodies in 3/4 than actually existed.

The 6/8 meter is not too common in the Peninsula. Some slow Romanian hora are in this meter, and the fast dances the Bulgarians call pravo seem to be in fast 6/8 rhythms; closer examination of the actual music, however, shows that most often the meter of these Bulgarian dances is compound duple (2/4 with a steady series of two triplets per measure).

IRREGULAR RHYTHMS

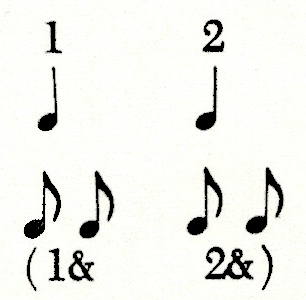

The structure of the irregular rhythms is based on various combinations of two-count and three-count units within a single measure, the counts being equal. In the regular rhythms to which most Westerners are accustomed, the units within a measure are always of the same kind. For example, a 2/4 measure, where both beats have two counts each, may be divided as follows:

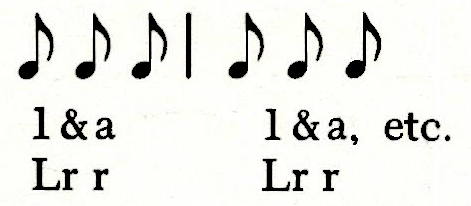

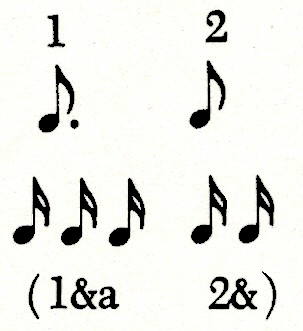

In an irregular rhythm such as 5/16 (called Pajduško rhythm by Bulgarian choreologists), there is one beat of two counts plus one of three counts:

It is possible, although rare in the Balkans, to have a 5/16 measure where the first beat has three counts and the second has two:

The Bulgarian Rŭčenica is danced to a 7/16 rhythm consisting of two beats of two counts followed by one beat of three counts:

Bulgarian dances such as Dajčovo are in a 9/16 rhythm counted

The 11/16 rhythm (known in Bulgaria as Gankino or Kopanica rhythm) is counted

The preceding examples are the most common of the irregular rhythms. There are other irregular rhythms much more complex, such as the Albanian and western Macedonian 12/16, counted

In Balkan dances there is no direct correlation between musical phrase and dance phrase as in the dances of other peoples. Westerners accustomed to four-, eight-, and sixteen-bar music are often surprised to find, in Balkan dance melodies, phrases of three, five, or other uneven groups of bars. Sometimes Balkan dancers are acutely aware of the number of bars, and their dances may vary according to the dictates of musical phrasing. Dancers of the vigorous Romanian brîu distinguish between a brîu in four measures Brîu pe patru and one in six measures Brîu pe șase.

It is very common, however, for a dance whose melody is in four- or eight-measure units to have three-, five-, or even ten-measure sequences of movements. The Serbian Vranjanka, for example, is basically a five-measure sequence of movements, danced to a melody composed of four-measure phrases. This means that each repeat of the dance sequence will be done to a different measure of the melodic phrase; four times five, or twenty measures, must be completed before the beginning of the dance phrase will again correspond to the beginning of the musical phrase. Interestingly enough, the song that accompanies Vranjanka (Šano, dušo") is so structured that it contains exactly twenty measures. Thus, the beginning of each verse corresponds to the beginning of the new dance phrase, even though chaos seems to reign within each verse!

Song and dance do not always work out so neatly, however, and many times the dance figure has such an odd number of measures that only at long intervals do the dance phrase and the musical phrase begin together. This proves no handicap whatsoever to the Balkan dancer, as long as the music is good and the basic rhythm is maintained.

Musical accompaniment for Balkan dances is provided in a variety of ways. Bagpipes, numerous types of primitive wind instruments, and strings are all found in the native stock. More recently (beginning in the nineteenth century) the violin, accordion, and clarinet have supplanted the older instruments. In Croatia and Vojvodina the old stringed tambura or tamburitza, formerly used exclusively to accompany singing, has been adapted and refined for ensemble work, and has now completely replaced the old gajde (bagpipes). Various types of percussion instruments are used in the Balkans, the most impressive being the Macedonian tapan – a large, powerful, goat-skin drum.

The dances of Montenegro, the Dalmatian Highlands, Bosnia-Hercegovina, and parts of Albania and Macedonia are done without any instrumental accompaniment; the only instrument is the dancers' own feet and the sound of the tinkling ornaments worn on the women's costumes. Occasionally a song (either solo or group) accompanies the dance. The use of vocal accompaniment persists even in areas where regular instruments are used; in these cases the voice may alternate with the instrument or may may be used simultaneously.

Most Balkan dancers move according to the musical beat and tempo furnished by the musicians. In Macedonia, however, the tapandžija (drummer) takes his cues from the steps of the lead dancer.

LEARNING IRREGULR RHYTHMS

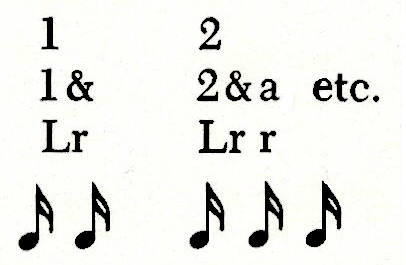

- Make sure you understand theoretically what is going on in an irregular measure; what makes these rhythms difficult for the neophyte is the use of the three-count units added on or "tucked into" the pattern.

- Sit on a chair with feet together on the floor so that you can use your lap as a drumming board, and place your left hand, palm down, on the left thigh, your right hand on your right thigh.

- Count out a series of 2/4 measures, slapping the lef thigh on the beat and the right hand on the offbeat.

- Now count out a 3/8 rhythm, slapping the left thigh on the first beat and the right thigh on the second and third.

- Practice these two patterns separately for a while until you are no longer conscious of your hands, but only of the rhythm.

- Now try a simple five-count rhythm, consisting of one beat of two counts followed by one beat of three counts.

- As this five-count becomes easy and natural, start to put more emphasis on the left-hand slaps and reduce the stress on the right hand to a silent pat. When you get to the point where all you hear is the sound of the left hand, you will be producing the rhythm you hear when an orchestra is playing Pajduško horo.

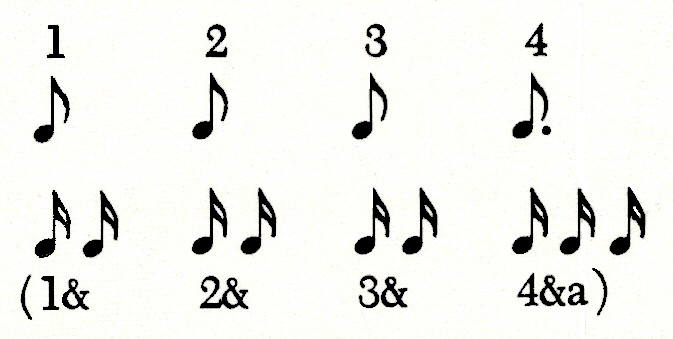

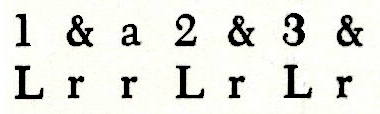

- Once you have mastered this five-count rhythm you can go on to others. Because of space limitations, we won't go into details on all the rest, but here are the "slap" patterns for some typical Balkan dance rhythms:

7/8 (with three-count at beginning):

Examples: Macedonian Lesnoto, Greek Syrtos-Kalamatianos, Bulgarian Kamišica.

7/8 (with three-count at end):

Examples: Bulgarian Eleno mome, Petrunino horo.

9/8 (with three-count "inside"):

Examples: Bulgarian Grŭnčarsko horo, Macedonian Što mi je milo.

DOCUMENTS

- Balkan and Israeli Folk Dances, a book.

- Balkan Religions, an article.

- Balkan Rhythms, an article.

- Balkan Table Songs, a list.

- Balkan Words from Turkish, an article.

- Balkans, a region.

- Béla Bartók and the Music of the Balkans, an article.

- Dick Crum, an article.

- Intellectual Fascination of the Balkans, an article.

- International Folk Dance Rhythms, an article.

- Irregular Rhythms, an article.

- Sex and Power in the Balkans, an article.

- Traveling in the Balkans, an article.

- Yugoslavia, a region.

From "Folk Dance Progressions" by Miriam D. Lidster and Dorothy H. Tamburini

Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Publishers, 1965.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.