|

The Society of Folk Dance Historians (SFDH)

Bulgaria and Its Dances

[

Home |

About |

Encyclopedia |

Periodicals | CLICK AN IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

|

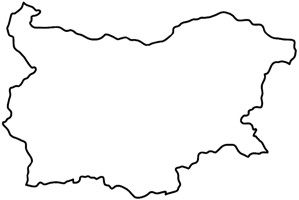

Bulgaria is situated in the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula. The country has the general shape of a rectangle; it is surrounded by Romania (the regions of Wallachia and Oltenia plus the Danube river) on the north, by the former Yugoslavia (Macedonia and Pirot Serbia) on the west, by Greece and Turkey on the south; and by the Black Sea on the east.

Bulgaria is situated in the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula. The country has the general shape of a rectangle; it is surrounded by Romania (the regions of Wallachia and Oltenia plus the Danube river) on the north, by the former Yugoslavia (Macedonia and Pirot Serbia) on the west, by Greece and Turkey on the south; and by the Black Sea on the east.

In relief, the country has the shape of a gigantic "M;" the two top strokes of the "M" being a chain of mountains that have been very significant in the historic past of the country. The Balkan range in the north is called the Stara Planina (old mountains) and the Sredna Gora (central highlands). In the middle of the "M" lies the vast and fertile valley of Thrace. In the south the Rodopi range, the Rila (well watered mountain), and Pirin (named after the Slav god Perun) Mountains form a natural barrier between Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey. The average height of these mountains is about 2,000 feet, with peaks up to 10,000 feet. The sides of these mountains are covered with pastures and coniferous forests. They also yield minerals such as copper, iron and lead, all of which are important in the economy of the country. Between these mountain ranges, the temperate climate of the valleys favors the cultivation of the vine, of fruit-bearing trees, and of the famous oleaginous rose. Forty-two percent of the numerous rivers flow into the Danube, forty-three percent channel into the Aegean Sea, and fifteen percent into the Black Sea.

Bulgaria has a superficial area of about 80,000 square miles. It is well irrigated by many rivers, the Isker, Struma and Martiza, and it boasts a temperate and uniform climate in the north and a Mediterranean one in the south. Agriculture is the mainstay of the country (wheat, corn, cereals, and fruit), as are also its exports (tobacco, wine, iron, wheat, and essence of rose).

To the tourist and visitor (Americans are now welcome), the country offers many original and picturesque sights. Along the roads which are often hand paved, one may come upon Tzigane camps where Romani still repair pots and pans and go in for spoon sculpture, or one may meet huge peasants astride their tiny donkeys. Invitations to visit local monasteries, of the 10th or 11th centuries, on panels which are inscribed in Bulgarian and French, are seen all along the road. On market days, one has the impression of being plunged right into the Middle Ages as one is surrounded by picturesque Rom, by colorful displays of native handicraft, and by the swarming crowds so typical of the Oriental-Slavonic races. On the other hand, such contrasts as that of the minaret of a mosque with that of the dam of a river will show that the country is straining toward the future, industrialism, and collectivism. The contrasts one sees are often strange and not always happy – such of new cities of Russian architecture amidst Roman walls, Greek columns, and faded Byzantine churches.

CITIES WORTH VISITING

Sofia

Sofia is the capital, which is situated on the west side, barely sixty miles from the Serbian frontier, and which contains 700,000 inhabitants. Traces of the old city have nearly all disappeared, especially since it was rebuilt in 1880. the town was founded by the Serdi, a Thracian tribe, and bore the name of Serdica until the Slavs renamed it Sredec; later, during the 15th century, it became Sofia, after the antique cathedral of St. Sophia. It was always, from the very first centuries up till now, a great economic social center. It became the capital of Bulgarian in 1878 after the first liberation by the Russians.

Around the city are grouped many Ūop villages, where the peasants have a folklore particular to themselves, and which we shall describe further on. Not far away from the city is the Bojana Church. This church was constructed in three sections, centuries apart; one section during the 10th century, another during the 13th century, and the last during the 19th century. It is one of the oldest relics of the Renaissance in Europe, and contains some of the first specimens of Bulgarian portrait painting. The artists of Bojana were among the first to use elements of everyday life as a theme for decoration. In a southerly direction, nestled in the mountain bearing the same name, is the Rila Monastery founded in the 10th century. It is one of the largest monasteries of the Balkans, a gigantic quadrangular figure, four stories high, complete with church and tower, and defies the ravage of time. Within its walls are wonderful frescoes and sculptures by the artists of the schools of Mount athos Samokov, and Banksko. It was for a long time considered the home of Bulgarian culture, especially during the periods that Bulgaria was under the domination of the Turkish beys and pashas.

Plovdiv

Plovdiv is the capital of the Thracian region, is situated in a plain, geographically in the center of Bulgaria. There is a legend that in ancient times, to vent his anger, a god threw enormous rocks from the skies and that seven of these fell upon the plain, near the Marica River that cuts the plain in half. The Thracians found these seven hills a safe enough place and elected to build thereon their first capital. Since then, the city has been variously named Eumpolpias, Philippopolis, Pulpudeva, Trimontium, Filibe and Plovdiv, depending upon its Thracian, Macedonian, Roman, Celtic, Gothic, Byzantinian, Slavonic, or Bulgarian occupants. The city has 200,000 inhabitants, is very animated, and serves as the seat of the International Agricultural Fair. It contains more relics of the past, and thus of Bulgarian history, than does Sofia; in some of the older parts of the city there are walls whose foundations were erected by Thracian tribes; the same walls, a few feet further will have foundations dating from the time of Roman Legions; and still further on may have been built by Slav princes. There is much to be admired, whether it is some example of pure Bulgarian or Turkish architecture, Bulgarian sculpture (Ste Marina Church for example), or the magnificent beaten gold work of Thrace, unrivaled in its kind such as can be seen at the Archeological Museum. South of the city, one can see the buttresses where, as legend has it, Orpheus was born; it is the site of a group of Pomac villages. On the east of Plovdiv, there are several flourishing cities: Stara Zagora, Jambol and Sliven, where large groups of Rom are now integrated in community life. To the north, between the Balkan Mounts, is the city of Kasanlik, world center of attar of roses, which is used in fabrication of perfume.

Varna (or Stalin)

Varna is on the coast of the Black Sea. Seaside resorts have sprung up that compare favorably with those of the French Riviera, or of the Russian Crimea. These have been erected upon the foundations of ancient harbors of Greek origin dating from 600 before the Christian Era (BCE). The town of Varna was then called Ulysses. This is where the great Ovid lived and died after he was exiled to the borders of the Roman Empire. The conglomeration of Phoecians, Phoenicians, and Greeks, with Tartars and Lippovians from the north during centuries of time has produced a peculiar people of mixed extraction.

Dobrudža

Dobrudža is a region to the north and in the estuary of the Danube, and possesses a very individual and typical folklore.

ORIGINS

Neolithic Period Until the Romans

As far back as the Neolithic period (10,000 to 40,000 B.C.), primitive tribes were living on Bulgarian soil, but they left behind them a few paintings and stone idols. Later, around 3,000 B.C., other immigrants arrived; among them were cattle breeders and artisans who worked with gold, copper, and ceramics. A civilization slowly evolved. These tribes lived along the Thrace valley, whose name identified them. It seems that they attained a high degree of civilization, if one can judge from their paintings and their gold work. They had many contacts of cultural, political, and economic nature with their neighbors the Dacians (later Romanians), the Hellenes (later Greeks), the Illyrians (later Albanians), and the Macedonians. During the Bronze Age, about 300 BCE, one of the tribes, the Odrysses, laid the foundations for a Thracian State which flourished during two centuries, in spite of invasions of Scythians, Sarmatians and Celts, until its ultimate conquest by the Macedonians.

The Romans

In 395, when the Roman Empire divided itself, Thrace remained under the jurisdiction of Byzantium, then the capital of the Oriental Empire which encompassed the whole Balkan Peninsula. Came the day (760 BCE) when Roman Legions invaded the country and the Roman Eagle spread its wings over these tribes. Existing cities benefitted by the construction of public baths, of new roads, and finally of more cities. But this was not accomplished without trouble: The Thracians put up a bitter resistance and one of their heroes, Spartacus, is still cited as an example of their love of liberty.

The Slavs

Because of the weakness of the Byzantine Empire, around 300 BCE, the Balkan States became the prey of barbarous tribes from the north: Visigoths Huns, and Ostrogoths. These hordes headed by such chiefs as the famous Alaric, plundered and burned Thracian villages and decimated the population. Following the example of these savage warriors, and enticed by these fertile regions, Slav tribes also descended from the north; seven of these tribes invaded the Moesia region that lies between the Danube, the Balkans, and the Black Sea. When the Byzantine tried to reconquer this territory, the Slav tribes united to resist them and thus formed a Slavonic State.

The Bulgars

Some time later, around 650 BCE, another tribe made its appearance; these Turkish-Tartars had first lived in the great Russian plains; forced to emigrate, they divided into three parts, one of which took refuge in northern Russia (400 miles from Moscow), a second disappeared into Attila's army and a third looked to the south for the hunting grounds and pastures it needed. Good horsemen and valiant warriors, they defeated, under the command of their chief Asparoukh, the army that Byzantium had sent to stop their progress and they united themselves with the Slavonic State against this common enemy. The new state was governed by a Khan with the help of Slavic and Bulgarian princes who composed the aristocracy. This union gave rise to an intense process of assimilation: after 200 years, Thracians, Greeks, and Bulgars finally created a Bulgarian nationality strongly influenced by Slavic civilization. The Bulgars, who had a lesser degree of civilization, disappeared without leaving any trace except that of their name.

EXPANSION OF THE BULGARIAN STATE

First Bulgarian State

During the following centuries the country grew in size and in strength. Many of the Khans (Kroum, Boris, and Simeon especially) considerably enlarged the territory at the expense of Serbs, Macedonians, Greeks, and Romanians, and drove back the Barbarians and Byzantines. The 8th and 9th centuries are considered as being the golden age of Bulgaria; a feudal nobility was formed (lords or Bojars), Christianity took hold of the country, and many new customs were introduced: the first Code of Law was promulgated, and of great importance for education, the Cyrillic alphabet, taught by the disciples of St. Cyril and St. Methodius was adopted. The old Slavonic culture, with all its refinements, soon radiated upon all other Slavic peoples. "Bulgaria, in spite of its vicissitudes and trials, was the cradle of Slavonic culture and education," wrote the Russian Academician N. Derjavin in 1914.

From all parts of the world, precious goods and objects were imported to decorate the golden-domed churches that filled the walled-in cities. But when the Khan Samuil died in his capital of Okhrid, Byzantium once more subjugated the Bulgars. This yoke was made all the heavier by the calamitous passage of the Crusaders through their cities.

Second Bulgarian State

In 1185, a revolution broke out, and the Khans took back lost territory and even augmented it by adding to it Serbia, , Albania, etc. But like most empires whose foundations rested on feudalism, it soon weakened, crumbled, and petered out.

Turkish Yoke

The Turks, of the Osmanlis branch, landed upon the peninsula and slowly and methodically destroyed the different kingdoms until one day Hungarian and Austrian armies prevented them from going further. The last Bulgarian kingdom to fall was that of Vidina, in 1393, and for 500 years Bulgaria disappeared from the geographical map. The Turks gave the country a new name: the Province of Rumelia. After a Golden Age, night and misery. The people were tortured to death or taken captive. Those who survived were treated as raias, the lowest caste of society. Bulgarians were forbidden to build churches of greater height than those of the Turks; neither could they own better horses, nor better clothing. Their children were taken away from them to be trained as janizaries (members of the Turkish infantry forming the Sultan's guard) of Turkish troops. Thus the social and economic development of this people was stopped completely for many centuries, its culture and its works destroyed.

There were many rebellions and these could fill many chapters. After some particularly revolting massacres, Europe finally realized the fate of this oppressed people and protested. The Tsar of the Russias came to the rescue of his Slavic brothers, possibly with dominance in mind. The first try was unsuccessful and 12,000 peasants perished. National insurrection then took place in 1877 and 1878. Russian armies, seconded by Romanian troops and by Bulgarian volunteers crushed the Turkish troops and the country was declared independent. In this war for liberation, 200,000 Russian soldiers died, as well as a large number of Bulgarians, among whom was the famous poet Hristov Botev, who perished in the Pirin Mountains at the age of 28 years as he headed a group of soldiers. The treaty of San Stefano declared that the country was now an autonomous province under Turkish sovereignty, and it was governed by a prince elected by the Sobranje (Parliament).

Third Bulgarian State

The period that followed its proclamation of independence was not an easy one for Bulgaria. Alexander de Battemberg, a German officer and nephew of the Empress of Russia, was chosen as Prince of Bulgaria. After two serious blunders, one an attempt to enlarge the country at the expense of Serbia, and the other an insulting letter addressed to the Tsar, he was forced to resign. The country was barely emerging from its ruins when the successor, Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Cobourg-Kohary, dragged it into a disastrous war, in 1913, and then into the First World War of 1914 to 1918. The politics of the country were greatly influenced by the fact that the Royal Family of Bulgaria was of Austrian origin. Every time that the people took sides with the German element instead of the Slavic one, it was to their detriment.

Social Communism

Socialism and then Communism appeared in the period between the two World Wars. An anti-Fascist revolution took place in 1923, headed by Dimitar Blagoev and Georgi Dimitrov, considered national heroes.

THE INDIVIDUAL

Bulgarian holds a very homogeneous population of 7,700,000 inhabitants, 88 percent of whom are true Bulgarians. The other nationalities are Macedonians (100,000), Turks (600,000), Rom (135,000), and the Pomaks – Bulgarians of Mohammedan religion – (100,000). The typical Bulgarian has a dark complexion, a square face, sometimes with the prominent cheekbones of Oriental races. He is well-built, thick-set, rather short as are most other Slavic races and very strong. He usually dresses in somber color, brown for men and black for women. His antecedents have fashioned him into a stubborn character, self-sufficient, and distant. He is suspicious of strangers, but if he does give his affection it is a lasting one. He is indifferent to his neighbors; he dislikes the Serb, even more does he dislike the Greek, and he has nothing but disdain for the Turk.

The cultivation of the soil has been most prominent in the moulding of the Bulgarian soul; 66 percent of the people still work on farms. A Slavic proverb says: "Place a Montenegran and a Bulgarian in a palace; the Montenegran will always remain a peasant. Put them both in a desert and the Bulgarian will soon have made a lovely garden whereas the Montenegran will remain idle." the Bulgarian has all the qualities and defects of most peasants; he is disciplined, sober, and hardworking. From his ancestors and his Oriental antecedents he has inherited the art of living and of relaxing along the shores of the Bosphorus Straight. He has an ancient humanism and a very lively sense of values, inherited from Thracian ancestors of Rome and Athens.

Long deprived of schools because of Turkish occupation, Bulgaria is now making up for lost time. In 1901, only 24 percent of the population could read and write, whereas now 99 percent of the student population attends school, and the university receives 25,000 demands for its 7,000 available places. For every 10,000 inhabitants of Bulgaria, there are 55 students, as compared with 17 in Great Britain and 36 in France. Forty percent of these students hold scholarships; about 38 percent of them are sons of employees, 30 percent of collective farmers, and 25 percent of workers.

Minorities are respected: there are 1,150 schools at the disposal of Turks, 43 for Romani, and 11 for Armenians. The >Bulgarian is the European who masters the largest number of foreign tongues, doubtless because of his historic past and of his geographic location.

THE REGIONS

Because of its rectangular shape, Bulgaria can be divided roughly in the following manner:

- – The upper part consisting of a series of tablelands graduated from the Balkans down to the Danube. Traditions here are influenced by neighboring Romania and Serbia.

- – The eastern section surrounding the capital Sofia which is inhabited by people, called Šopi, who have their own very distinct character.

- – The middle section which consistes of a large plain of which the river Marica is the backbone. The city of Plovdiv is situated in the center and is the capital. This region is Thrace and has its own particular traditions because of its historical past.

- – The western part ends in the marshes and on the beaches of the Black Sea. It is called Dobrudža. It is a poorer region than Thrace and Šop but has a personality of its own.

- – The Rodopi and the Pirin mountains are found in the south. >Macedonians and Pomaks, as well as neighboring Greeks and Turks, all contribute their influence upon this region.

As was the case in most ancient races, the first sculptors were shepherds. They decorated their canes, tools, and boxes with simple geometric designs. Later, flora and fauna were used as models and later still the human figure appeared in their works. All these decorations were sculptured in relief. The wooden houses that were built through the centuries were decorated with these same primitive designs by shepherds who still practiced their art whenever possible, even after they had taken up another trade. Nevertheless, without Turkish occupation, Bulgarian sculpture might not have attained the degree of perfection that it did later on. With the advent of the Second Bulgarian State (1185 to 1393), sculptors excelled in their line. The art of sculpture was peculiar to certain families where corporations were set up and in which the trade passed from father to son. The cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul in Veliko Târnovo, the St. Nicholas at Okhrid, and certain decorations in the Rila monastery are among the few monuments still existing today that vouch for their artistry. But the Turkish invasion destroyed all economic and artistic activities. The craftsmen whose lives were spared took refuge in safer regions.

During the four centuries that followed the fall of the Bulgarian Empire, the churches and houses destroyed by fire were rebuilt; but as the Turks forbade the building of anything that might rival their own constructions, the new churches were half sunk into the ground and decorated in the simplest manner with few popular motifs. Near the end of the 18th century and in the beginning of the 19th century, a popular movement, inspired by new political ideas, took shape in the country. Its aim was the liberation of the country from Turkish yoke. Painters and craftsmen joined revolutionaries in the general striving. It was the beginning of the Bulgarian Renaissance.

At the same time, through diverse influences (that of the Russian Tsars especially) the Turks had to relax their hold upon Bulgaria and life ran a smoother course. Energetic and hard-working, the Bulgarian people regained hope. Commerce flourished and wealthy tradesmen built houses of a new, different style. These buildings, two-stories high, provided carpenters with plenty of work; everything was very ornamented, sculptured doors, decorated columns and walls, ceilings trimmed with rosettes, etcetera. These craftsmen made it a point of honor not to repeat themselves. They were profoundly impressed by the Rococo and Baroque styles, introduced to the country by material imported from Europe. By using these styles in the manner of a frame for their own work. Bulgarian sculptors attained new heights in the development of their art. As medieval craftsmen expressed themselves best in religious decoration, so did Bulgarian artists find a new goal and new elements of artistic expression in the decoration of their homes and various constructions. So that, with a basis of local traditions influenced by Occidental decorative art, there resulted a very particular style: the Bulgarian Renaissance.

From Mount Athos in Chaldicia, came their most famous masters in the art of Bulgarian sculpture. They recruited a number of craftsmen to fulfill the important contracts they undertook. Then several schools of sculpture were formed:

- – The School of Trjavana, already opened in 1804.

- – The School of Samokov under the early influence of the Masters Andonivi and Atanas (1792 to 1827) whose most beautiful works are in the Rila Monestary.

- – The School of Debar or Mijaska, now in Macedonia; the Iconostasis of the St. Ivan, and the Church of the Ascension at Skopje are among the finest examples of its art.

- – The School of Bansko also in Macedonia, is responsible for the Church of the Holy Virgin in Assenograd, and for the Church of Ste Marina at Plovdiv.

EMBROIDERY

No one who has seen specimens of Bulgarian embroidery can help but admire their artistry and their technical perfection. In this art, as in wooden sculpture, the Bulgarian craftsman has shown himself in the plenitude of his talent. Embroidery is used especially to decorate costumes. Tunics (saja and soukmani), waistcoats, and shirts – all are so embellished that even work garments seem festive. The basic material of these garments is of a plain color; white in cotton, linen and hemp, and colored in hand-woven materials. The most important characteristic of the technique of Bulgarian embroidery is the closeness of the stitches. These, especially those called "cross-stitch," are so close together that this gives the work great colorfulness. Certain pieces are so heavily embroidered that it is the basic material that shows up as the design. The uniformity of the pattern is assured by the counting of threads in the weave of the basic material. As the embroiderer works from the wrong side of the cloth, this demands not only a perfect technique but also a great imagination.

The designs are composed and sketched during wintertime, often by only the light of a fireplace or of one miserable lamp, which does not ease the task of choosing colors and forms. At springtime, the women group together and prepare for the first feast-days of the year. This becomes a real competition as, at a fixed time, they display their work in front of their houses and all neighbors make the rounds to criticize and to admire.

The designs follow the cut of the garments: necklines, edges of the tunics, seams and hems, all smaller designs. The motifs are usually flowers, plants, sometimes tools, human beings (dancers in chain dances), or animals. The pattern is first drawn on the material, and because of the technique of counting the threads, only geometrical shapes are used. Circles thus become more or less rectangular shapes, and heads are triangles. If the design is very large, it is divided into sections that are embroidered separately. The whole work may have no special meaning for outsiders, but it has a very special one for the peasants who know the name of each design and the significance of the colors employed. In the Bulgarian embroidery, everything is shown in its original color. Thus a serpentine figure ornamented by green dots will take a special significance when one knows it is called "the vine."

The thread is usually of wool. Cotton has recently made its appearance, as has metallic thread, but wool is most popular. This wool is of a various colors and shades; red predominates, followed by green and blue; black is seen in varying quantities, depending upon the region. Yellow is only used on small areas. White, brown, and orange are local colors employed in certain costumes only. White for example, is lavishly used in Šop costumes.

Another characteristic of Bulgarian embroidery is the harmony of the colors and the lively rhythm of the whole effect. In a feminine Thracian costume, as described later, the collar, the front rectangle, and the hem of the tunic, in spite of their various designs, harmonize with the top tunic (spukman) that is worn over the first and that is of a different color and design. An apron and a coif complete the costume, every part of which has been conceived in view of the total effect. Only an expert could trace the origin on these patterns, but we may conclude, after comparing them with those of other countries, that Bulgarian embroidery is of the "ancient Slav" type and that Byzantine, Turkish, and European influences can be seen in them. Their richness remind one of ancient Coptic and Syrian embroidery. As in most traditions this is a local art. The main lines of the garments are standard, and so are the designs in each region. The rest varies with the taste of the artist, the social status of the wearer of the garment, and the regional economic fluctuations. In youth, the designs are childish; in feminine garments, designs are gay and light; then, as with a flower that blooms, the embroidery becomes richer and more complicated as the wearer approaches the time of marriage; after the birth of their first child, the women wear paler colors, and the designs even change to suit older people. There has been a certain decline in the art of embroidery in Bulgaria, but tradition is still deeply rooted and is now part of the school program for young girls.

DANCE MUSIC

There is a certain chronological order in the appearance of the instruments that compose a Bulgarian orchestra and we shall respect this order in the following description.

Songs

Originally, the Horos (chain dances) were sung for the feminine circle dances, the singing taking an antiphonal form: two women singing the theme and two others answering them. Seldom, except in the Rhodopes, does one hear male quartets, or diaphonal singing (na bučene in Bulgarian), that is, a woman singing the melody and two other women singing lower key melodies as in the drone of bagpipes. Nowadays, these Horos have gone out of fashion except in the south and southwest, and even there only older dancers participate.

Drums

In all nations, the drum is the most ancient instrument. Even today, among the Rhodopes, there are Horos (usually for men) that are danced to the sole accompaniment of one or several drums. Generally, the drum is the size of a bass drum and is played with a big straight stick on the right side with a long supple baguette, for ornamental rhythms, on the left side. Only once have I seen a drum like those used by the Israelites (goblet drums), having the shape of an amphore, held upside down under the left arm, and played with the fingers.

Wind Instruments

There are many different flutes: the dvojanka (double flute), tsaffaras (little pipe), djudjuk (black pipe), but the kaval (an end-blown flute) is the most popular; it possesses the greatest flexibility for modulations. After the kaval, the gaida (bagpipe) are the favorite musical instruments; they originally came from Greece< but in Bulgaria they assume many different shapes. Unlike the Scottish< bagpipe, which has three drone-bass, the Bulgarian bagpipe has only one. The gaida is keyed to do, re, on the first octave lower than the basic tone of the instrument. Good musicians use the half tones by partially stopping the holes of the instrument. The gaida is a less flexible instrument than the kaval, but the sound is stronger and it is very suitable for dance music.

Stringed Instruments

Possibly of Arabian or Turkish origin, the Bulgarian rebec (a multi-stringed instrument played with a bow) is called gădulka (and sometimes kemenče or kopanka). It has two arrangements, the shape of a pear, and is used to provide the chords to dance music. The mandolin or lute is called tambura (or sometimes bulgarja). Usually, it has four to six strings, though in the south it may have up to twelve strings. The violin was introduced around the 18th century and is now a popular instrument. The gusla (a single-stringed, long-necked instrument played with a bow), an ancient instrument, is now unknown.

Wind Instruments

Since the last two wars, Bulgarians have returned from their barracks with two new instruments: the clarinet and the coronet. These are very popular and are played with great virtuosity. Solo improvisations on these instruments are the joy of dancers. The accordion is the latest addition to the orchestra, and is in demand for solos.

Orchestra

The composition of the orchestra varies with the regions. In the north of the country, it may be composed of kaval, gaida, and often of clarinet, coronet, drum, and violin. The southern and western regions are more traditional. There will be the gaida and kaval, or gaida and gădulka, and here and there the Horos will be sung. The accordion is slowly replacing ancient instruments and is played alone when it is used. The influence of itinerant musicians is important enough but not so much as it is in Romania and Hungary. Most often, the musicians are >Bulgarians of the region. When they are grouped in an orchestra, they play monophonically (all playing the same melody without harmonizing) and so do not use their instruments to the best account. The melody is usually some song whose words have been long forgotten. However when they improvise, each in turn, the musicians do use all the resources of their instruments; in these cases the drum marks the rhythm for the music and for the dancers.

DANCE LOCALES

Bulgarian dances may be watched or learned in two very different locales: at the gatherings of peasants or of various cultural groups who dance upon the stage.

The people still dance often – even if, in the past, dancing may have had an even more important role than it has now, as a means of recreation. Today, many other pastimes such as theaters, movies, etcetera, are, because of collectivism, open to the public. But peasants still dance at the fairs, at weddings, at harvesting, and on certain national or religious holidays, such as the Saint Lazare, Easter, and at the Carnaval before Lent. In the cities, Horos are still in favor. During my stay in Sofia I heard Horos alternating with American jazz at fifteen-minute intervals in a café off the main square. There are many such dancing places.

Dance groups are organized, as they are in all socialist-communist countries. In a village, the chief organizers are: the village mayor, the chief of police, the Communist party's secretary, and last but not least, the chief of culture, whose responsibilities are many: he must build or furnish a building to serve as an art center, find and exhibit local art, show it to passing art seekers, promote cultural groups, and stimulate artists. Dancing, singing, amateur theatricals, and even puppet shows are among the activities of these groups, also enjoyed by every workers' syndicate. By grouping future professional artists, and by giving them these means of expression, the cultural groups play an important role in the nation's artistic development. Of the 12,000 groups that exist today in Bulgaria, at least one quarter specialize in dancing. These groups composed of students, workmen and farmers, dance only their own regional dances. Trips across the country, or abroad, and prizes given by the State, are the rewards of the local, regional, or national contests. Many youngsters then participate in regional amateur teams. One of the best known of these that I was able to observe for several weeks is that of Vladimir Majakovski in Sofia. It has a social center where boys and girls can practice their favorite sports after dancing lessons. There are about 160 members of this group: 40 dancers, 100 singers and the remaining members play in the orchestra and look after the administration. They have a minimum of two practices of three hours each weekly, preceded by some forty-five minutes of rhythmic exercises specially designed to limber them up for their regional dances.

If a group is exceptionally good it may become professional, that is, the dancers will work full time and will be remunerated by the Government. There are five of these groups at present in which young dancers graduate, after being auditioned: the Koutev group, the Army group, that of the Ministry of Labor in Sofia, the Macedonian Ensemble at Blagoevgrad, and the Thracian Ensemble of Plodiv. Singers and dancers work about five hours a day, five days a week, and are engaged later as professors. Choreographers are usually remunerated for every time their choreographies are used, according to their copyright. They go from village to village collecting needed material with the aid of tape recorders and cine-Kodaks. The dance thus collected are then grouped as a "suite." Certain choreographers work in collaboration with ethnic institutes, whereas others take greater liberties with folklore. Ensembles occasionally interpret dances from neighboring countries, but more as a friendly gesture, as they really have little interest in others folklore, except possibly in the Hungarian and Russian dances because of the ballet-like techniques these dances require. At the town of Sliven, there is a remarkable Romani ensemble, and elsewhere three Turkish and a few Macedonian groups. Few Bulgarian will dance Macedonian dances whereas Macedonians dance a few Bulgarian Horos. Romani seldom have any dances of their own, in fact I only saw one, which resembled a Kolo (going toward the left, a rarity in Bulgaria).

THE DANCE

It is probable that some readers may skip the first sections to come directly to that of "The Dance." So here, I shall give them an important warning: One must never generalize, nor be too categorical on the origin or authenticity of a given step or dance. The reasons for this being (1) the diversity of cultures whose influence may be felt, (2) the lack of stability or geographic boundaries, and (3) the natural evolution of the dances. This subject is fascinating one and it would take a lifetime of study to analyze Bulgarian dances, in which Oriental and Occidental, Slavic and Mussulman influences have been traced from medieval to modern times. Each century sees changes on the geographical map; today's boundaries are still very fluid. Bulgarian Šop people live in Serbian today, as their Macedonian cousins live in Sofia. In many cities two people live side by side and yet keep their distinct personalities as in Canada's Montréal for example.

Let us remember that folk dancing is living and dynamic. What we dance today is thus different from what our children will dance tomorrow. A choreography is a crystallization, at a given time (as a photo in a family album, for example) of a ritual that may be several hundred or thousand years old. Choreographies describe dances that may differ with the locality in which they are danced, and on whether they are danced by father or son, on either of whom army or school may have had some influence.

The Horo is considered the national dance of Bulgaria, much like the Yugoslav Kolo, the Russian KHorovod, the Greek Syrto, and the Romanian Hora. This is one of the most ancient dance formations known. On Sunday afternoons, the villagers gather upon the public square, and the orchestra, sometimes of Romani origin, plays a straight dance or Pravo Horo. The dancers form a circle around the musicians; the circle keeps growing to the point where new circles must be formed around new musicians. Dancers on the outside of the circumference can only hear the beat of the t&251;pan (bass drum) and so dance more slowly, but as they approach the orchestra, their steps increase in tempo and become more involved. The musicians often circulate within the circle to keep it in line. Simple Horos are followed by line dances, the leader haggling at length with the musicians on the price of their services for an hour or two. Sometimes, the musicians and dancers vie with each other, especially when dancing the Rûčenica; the orchestra changes rhythm from 2/4 to 7/16 for example, to the great glee of the dancers. These changes are greeted by shouts and encouragements from the bystanders. As the evening progresses the tempo increases and the dance gathers speed. Without warning, the gaidas and tüpans stop playing and all participants leave the field in complete silence.

There is an infinite variety of Horos. For example, song and music may be changed according to the seasons of the year. It has also been noted that several changes can be introduced into the melody of a dance tune in one day. Certain occasions and feasts call for special Horos: Feast of St. Lazarus, Carnival of Lent, and Easter for example. Some dances have been dedicated to local heroes, such as Gankino Horo (Ganka, a young girl). The choreography of others borrow from different trades certain revealing gestures.

There are Horos suitable for every occasion. The peasants are influenced by all that is part of their everyday life: sheep (Ovčata Horo), rabbits (Zaješkata Horo), and bears (Mečeškata Horo) are the inspiration for various dances. From one region to the other, wedding guests, musicians, or harvesters bring variations and new interpretations to existing dances.

Here is a general classification of the various dances of the country. (Regional and ritual dances will be described further on.)

- Horos that go in one direction only (rhythm 2/4); Pravo Horo.

- Horos with a limping step usually going in one direction only, but sometimes coming back in the oposite direction (rhythm 5/8): Pajduško Horo.

- Horos that advance first in one direction and then in the other (rhythm 9/16): Povurnato Horo.

- Rûčenica: couple, trio, or line dances (rhythm 7/8).

REGIONAL STYLES AND DANCES

Throughout the country, the Bulgarian dancer has a common and peculiar characteristic: he stamps the ground in a frantic and stubborn fashion. His peasant ancestry and his love of the soil are well expressed in this gesture, as it is in others borrowed from that of various trades and crafts. His movements are virile, abrupt, sometimes teasing, or mocking. As most peasants the world over, he has a well developed sense of humor, at times slightly erotic in older dancers; all have great facility in improvising dance steps. Each takes great pride in giving his Horos a personal touch. Men, here, are their best; proud, exuberant, constantly improvising, they vie for attention. Women dance in a more reserved and simplified manner. Couple dances give free play to body and hands. A stranger does not easily master these Horos which call for stamina, practice, and natural rhythm.

Šop Region

There is a great variety in the rhythm of Šop dances, most of which are played upon the accordion. Typical of these dances are the small-stepping Šopsko Horo and Graovsko Horo of 2/4 rhythm. Dajčovo Horo (9/16), danced in line and one spot (na prat) and called by a leader; Gankino Horo or Kopanica Horo (11/16); circle dances, Petrunino Horo (13/16), etcetera.

The village peasants form an enormous circle where men and women are grouped either together or separately, according to local traditions; four or eight men step forward to the center of the circle, and one after the other, dance variations of the basic steps that the circle of dancers then take up in a more simplified manner. The dancers lean forward, the weight of the body being upon the tips of the toes. In this leaning forward position (called prisednalo) the knees give the whole body a sort of vibration; this movement, from feet to shoulders, is called natrisane, and gives the impression that the dancers barely touch the ground with their feet.

Thracian Region

The rhythm of the Thracian dances is not as complex as that of the Šop Horos; the dances are accompanied by singing, or by an orchestra composed of kaval, gŭdulka, tŭpan, etcetera. The Trakjisko Horo is danced everywhere with variations; it is danced by men, with a foot movement that resembles tap dancing, called tropolone. In this region, the Trite Pŭti (2/4), Kamišica (7/8), Pajduško Horo (5/8), and Kopanica (11/16) are also popular dances.

At the beginning of the Thracian dances, the music is slow; married men start the Horo, holding hands and advancing calmly as they balance hands and torso to the rhythm of the music; married women next enter the ring; followed by the unmarried girls; and finally by the bachelors. The dance, at the start, is quite solemn, even contemplative; after some time the rhythm becomes faster and the stamping of the ground more and more vigorous. But even then, Thracians never lose their innate dignity. Unlike the delirious enthusiasm shown by the Šop, their feet seem glued to the ground, bodies balancing, and hands, at times, seeming to underscore the movement of the feet.

Dobrudja Region

The Rŭčenica here takes a special and peculiar form; the men, forming a circle follow each other without holding hands and perform a series of gestures and steps that illustrate their daily labor. Horos with a simple 2/4 rhythm, such as Rŭka, Danec, Opas, and Zborenka, accompanied by a kaval and gaida orchestra, are also popular, and occasionally one sees a Pajduško Horo. The dancers form a ring and hold front-crossed hands in the na lesa [belt hold] position. Swaying slowly as the music starts, they gradually become more excited, their whole bodies seeming to shake from emotion; they alternately calm down and become excited all over again. The women though more reserved than the men, twist their shoulders from left to right to reveal their excitement.

RITUAL DANCES

During the Paleolithic period, rituals began, as men first conceived the idea of God or gods. Masks, incantations, and rhythms were an integral part of their lives and later became the basis of religion, theater, and dance. These three, masks, incantations, and rhythm are very intimately involved in the Bulgarian history and civilization. The changes in values-set of our century has dimmed the meaning of these ancient rituals, but Bulgarian traditions still abound in rituals that attest to the liveliness of its folklore.

Christianity transformed and gave new significance to many of these pagan rituals. The objective of most ritual dances has been forgotten throughout the ages, nevertheless these Horos have endured the passing of years. Many of these dance elements date back to pre-Christian era; such are the grouping in odd numbers of 7 to 9 dancers (witchcraft), gigantic or monstrous masks (vestiges of cults to the giants of antiquity), Neolithic divinities, such as Child-Woman, Man-Woman, etcetera.

SEASONAL CELEBRATIONS

The most outstanding theme persisting even to this day is that of a dance to implore the benedictions of the gods upon harvests, and the fertility of the land and its inhabitants. Folklore is thus intimately related to the seasons, and we shall follow its chronological sequence.

- December 24: KOLEDUVANE. From house to house, a group of singers present their Christmas greetings and carols; in return they receive wine, bread, and cheese. An interminable chanted blessing by which they express their thanks is often interrupted by the "amen" or moqueries of the participants. The singers dance Horos on their way from one house to the other. Near Sofia, and other regions, they may be accompanied by a couple disguised as Bride and Old Man dancing a rŭčenica.

- January 13-14: Feast of St. Basil: LUDUVANE. The ritual dance peculiar to the regions of Samokov and of Koprivštica is the ring dance. On arrival to the feast, the young couples throw a bouquet of flowers, to which is affixed a ring, into a pail of water. As they throw rings and bouquets, qualities or the short-comings of whoever may marry the owner of the ring are publicly sung. At the beginning of the ceremony, barley that was first thrown in the pail, is now sprinkled upon the ground. Everyone eagerly gathers a few grains in order to feed their chickens, as these grains supposedly have the magical property to make the hens lay more eggs.

- SURUVAKARI. At the same time as Luduvane, in the regions of Breznik and Radomir, masked dancers appear who wear pointed hats some six feet high, bells around their waists, and who carry wooden swords. They are followed by dieties and clowns; a Physician, a Bride, animals, and even youngsters disguised as trains and planes. Running from house to house, they bring gaiety and wishes for good health. In ancient times, two groups, upon meeting, staged mock battles.

- February 1 and 14: ST. TRIFON ZAREZAN. Masks and special Horos appear on the "pruner day." Traditional folklore hails him as the patron saint of vine-growers, wine-producers, and bar owners.

- Spring Carnival: KUKERI. Masks similar to the Suruvakari (described above) appear in the Elhovo, Aito, Karlovo, and other regions.

- KATO CIALOTO. The devils appear and the peasants hoist a mast at the top of which a basket of straw has been placed, to be ignited during the period before Lent, followed by dancing the local Pajduško around it. Then with the advent of Lent, dancing is prohibited and only the young girls are allowed to gather on the outskirts of the village for Danets or Bujenets. This dance is made up of steps half-walked, half-run under the instructions of a leader calling girl disguised as a man, accompanied by a very young girl dressed as a married woman. This couple symbolizes married fertility.

In eastern Thrace, dancers wear gigantic masks over feminine soukmans (most often a sleeveless dress, but in some places with short or long sleeves) and carry out dramatic dances that include the inevitable bride, king, and Arab. A ceremonial of harrowing and sowing follows.

- Saturday before Palm Sunday: LAZARUVANE. The dance of the Lazarkis, in the Sofia and Pomeranian regions, is one of the most beautiful Bulgarian ceremonies. The maidens wear richly embroidered dresses for this dance. They also garnish their headdresses with pale green grass. Under the watchful eye of a chaperone (kumica), groups of five to fifteen go around the village houses, singing Horos to announce the advent of spring. Sometimes, a hint of marriage or of fertility is underlined in the ritual.

- Pentecost: RUSSALI. The Russali can be found around Nikopol and Orjaklovo. It appears that this dance was borrowed from their Romanian neighbors living on the other side of the Danube. A group of dancers, always in uneven numbers, gathers around a chief who carries the sacred standard. This man is entrusted with the costumes, flags, and standards during the year and is appointed to teach the dances correctly. The dancers wear white costumes adorned with trinkets, small bells, medicinal herbs on their hats, and carry a special stick. This dance is meant to cure the sick of the community. It is a fast rousing dance and will even throw the dancers into a trance. The latter are quickly brought to earth by their leader who uses his stick at the least mistake.

- Harvest time: DJAMALI. During Russali, an all-night feast with singing and dancing is organized to attract good weather. More rejoicing coincides with the end of the harvests when the young generation has time to think of marriage.

- June 2 and 3: NESTINARKI. In the mountains of Stanja, the Feasts of St. Helen and of St. Constantine are observed by fire dances. In the morning, the tŭpan and gajda are heard. The Nestinarka (female fire dancers) perform in a chapel specially erected for the occasion. The people form a procession and dance around the chapel, and then around a mineral spring reputed to have supernatural healing powers, with the whole village joining in with the hope of thus obtaining good health. The Horos follow one another the whole day long. The feast carries on into the night up to the climax: the Nestinarka goes into a trance and circles the live coals with ikons (from the Greek for image, a religious painting in the tradition of Eastern Christianity) in her arms, then steps into the fire for several seconds.

- Autumn: KAMILATA. A "Camel" browses in the fields at night in the Elhovo district. The peasants fabricate this monster along the lines of the hobby horse (English, Basque, or Catalonian). It goes around the farms wishing the peasants luck with the harvests that are coming to an end. In return the farmers give him grain or wheat.

DOCUMENTS

- Bulgaria, a country.

- Michel and Marie Cartier, an article.

Used with permission of the author.

Reprinted from "Bulgaria" in Viltis Magazine, September-November 1981, Volume 40, Number 3, V. F. Beliajus, Editor.

Previously printed in the June 1960 issue of Viltis.

This page © 2018 by Ron Houston.

Please do not copy any part of this page without including this copyright notice.

Please do not copy small portions out of context.

Please do not copy large portions without permission from Ron Houston.